Captain James Cook and absent presence in First Nations art

- Written by Bruce Buchan, Associate Professor, Griffith University

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

In Vincent Namatjira’s Ramsay Award winning Close Contact (2018), the artist construes Captain James Cook as the reverse image of his own self-portrait. The colonising presence of Cook looking toward a colonial future is satirised by making another present: Vincent Namatjira’s self-portrait looks out in a diametrically different direction.

Towards what, exactly?

Australia’s link to Cook has always been mediated by iconography. Cook was a promise recollected in pigment, bronze and stone to a nation at war with its first inhabitants and possessors.

Cook, and the violence of colonisation in his wake, embodied a claim to a vast inheritance: of Enlightenment and modernity at the expense of peoples already here.

Since his foundational ritual of possession, First Nations people have called for a reckoning with Cook’s legacies, and in recent years First Nations artists have reinvigorated this call.

By invoking the presence of Cook, they ask their audience to recognise how colonisation and empire rendered them all but absent – and his celebration today continues to do so.

Taking possession

In Samuel Calvert’s 1865 print, Cook Taking Possession of the Australian Continent on Behalf of the British Crown, the noisy presence of the newcomers’ industry and weapons drives two huddled Aboriginal men into the bush.

Captain Cook taking possession of the Australian continent on behalf of the British Crown A.D. 1770 (c. 1853-1864), colour process engraving.

National Gallery Victoria

Captain Cook taking possession of the Australian continent on behalf of the British Crown A.D. 1770 (c. 1853-1864), colour process engraving.

National Gallery Victoria

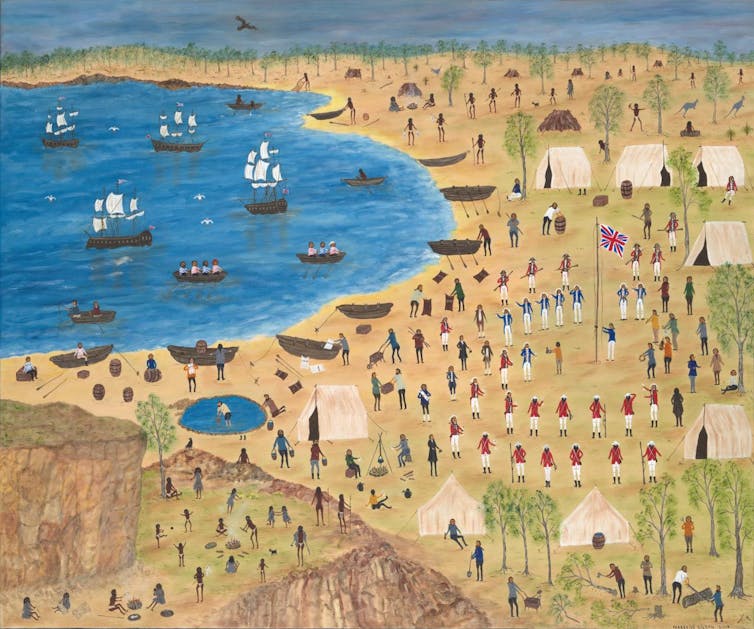

Wathaurung Elder Aunty Marlene Gilson re-worked Calvert’s image in The Landing (2018): widening the lens to show peoples living in the landscape.

Gilson imaginatively runs together Calvert’s imagery with accounts of Governor Phillip’s later landing. As the flag is hoisted ships hover in the bay. Colonisation was a process of denying who was already there, the First Nations families and figures Gilson captures in lively habitation on land and water.

The landing, 2018, Marlene Gilson, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2019.

© Marlene Gilson

The landing, 2018, Marlene Gilson, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2019.

© Marlene Gilson

Gilson challenges the mythology of empire: that empty territory needed no treaty.

Gilson’s image is also a homage to Gordon Bennett’s earlier reworking of Calvert in Possession Island (1991). Bennett deliberately obscured Cook and his companions, with the exception of one dark-skinned servant. The presumptuous act of possession is only glimpsed behind a Jackson Pollock-like forest of lines. Visual static intervenes. Terra nullius interruptus.

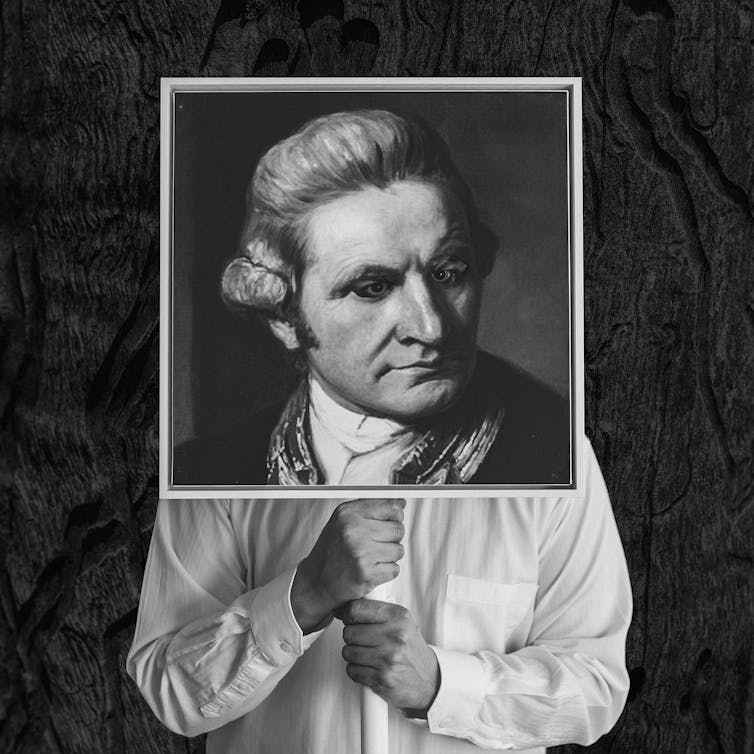

This obscurity stands in marked contrast to Christian Thompson’s Othering the Explorer, James Cook (2015). Part of his Museum of Others series, his images invite us to consider the effacement of First Nations people by colonial authority and knowledge.

Dr Christian Thompson AO, Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook), 2016. c-type on metallic paper, 120 x 120 cm, from the Museum of Others series.

Courtesy of the artist & Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin

Dr Christian Thompson AO, Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook), 2016. c-type on metallic paper, 120 x 120 cm, from the Museum of Others series.

Courtesy of the artist & Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin

Thompson superimposes Cook’s head and shoulders on the artist’s own. His choice of images is deliberate, the 1775 Nathaniel Dance portrait of Cook in full naval regalia glowering over his Pacific “discoveries”.

Official portrait of Captain James Cook, c 1776, by Nathaniel Dance.

National Maritime Museum, United Kingdom

Official portrait of Captain James Cook, c 1776, by Nathaniel Dance.

National Maritime Museum, United Kingdom

Since European colonisation, the assertion of the discoverer’s right to possess has erased the rich tapestry of prior ownership and belonging. In Thompson’s wry self-effacement, Cook’s superimposition is a reminder of someone already there. This was always the coloniser’s ploy. Presence as absence is a conceit of colonisation.

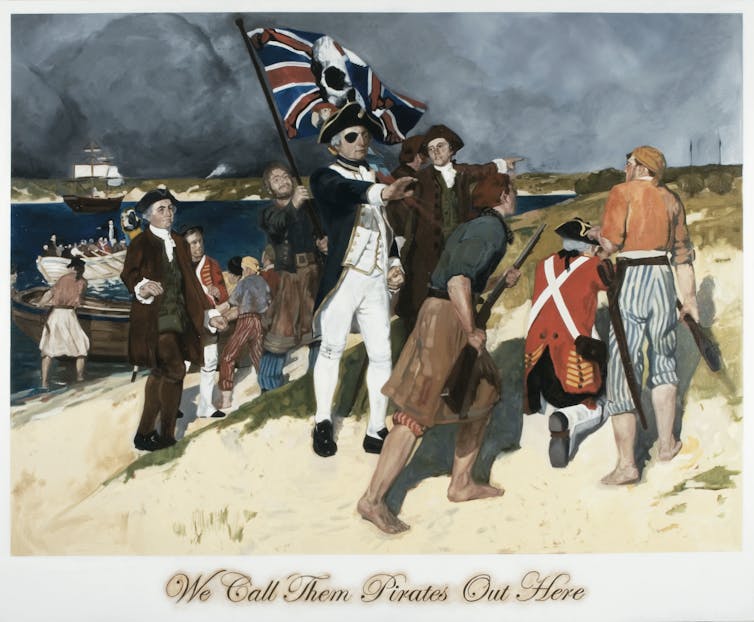

The presence of absence informs Daniel Boyd’s re-imagination of Cook’s landing in We Call Them Pirates Out Here (2006), a re-working of E. Phillips Fox’s Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay (1902).

E. Phillips Fox, Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, 1770, c1902.

National Gallery of Victoria

E. Phillips Fox, Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, 1770, c1902.

National Gallery of Victoria

Phillips Fox portrayed Cook restraining his men from shooting the distantly pictured “natives”. This was empire as it wished to be seen: peaceful, British, white and triumphant.

Boyd plays on the flattery of imperial self-imagining by exposing the wilful piracy of colonial possession. Boyd’s Cook cuts the same imperial dash, but with an eye patch and skull and crossbones on the Union Jack behind him empire is revealed as the pirate’s resort.

Daniel Boyd, We Call them Pirates Out Here, 2006, oil on canvas, Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families, 2006.

© Daniel Boyd

Daniel Boyd, We Call them Pirates Out Here, 2006, oil on canvas, Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families, 2006.

© Daniel Boyd

Challenging mythologies

The growing First Nations challenge to Cook’s iconography highlights his continued presence in our nation’s colonial mythology.

It is a challenge to Cook’s elevation as hero of the modern Australia built on Indigenous erasure. Jason Wing’s bronze bust of a balaclava-wearing Captain James Crook (2013) symbolises that challenge.

Jason Wing, Captain James Crook, 2013, bronze, 60 x 60 x 30cm, edition of 5. Photograph by Garrie Maguire.

Image courtesy of the Artist and Artereal Gallery.

Jason Wing, Captain James Crook, 2013, bronze, 60 x 60 x 30cm, edition of 5. Photograph by Garrie Maguire.

Image courtesy of the Artist and Artereal Gallery.

Wing’s addition of the balaclava forces us to confront Cook’s legacy not as the projected shining icon of Enlightenment, but as a mythic presence built on deliberate theft, dispossession and violence.

These are only a small collection of artists reconsidering the place of Cook in our collective memory. Provocative, challenging, arresting, often satirical and sometimes funny, First Nations artists powerfully challenge us to reconsider Cook and our nation’s iconography.

Within the art lies an open invitation to reflect on who we have become and where we are headed.

This invitation is highlighted in Fiona Foley’s most recent retrospective, named for a song by Joe Gala and Teila Watson performed in Badtjala and English: Who are these strangers and where are they going?

The song weaves together the narratives of the First Nations people who first saw the Endeavour make its way along the coast. Together with the photographs and installations drawn from across Foley’s long career, the retrospective is a powerful affirmation of continuing presence: in 1770, in 1788, and today.

As we confront the Cook commemorations, Foley’s and the Badtjalas’ question, like Namatjira’s double-sided self-portrait, is a nudge to our nation’s future. Who are these strangers and where are they going?

By reminding us that the question was asked of Cook’s sudden presence in 1770, we must ask it again of ourselves to confront the absence his possession still makes present for us 250 years on.

Authors: Bruce Buchan, Associate Professor, Griffith University