Snowy 2.0 threatens to pollute our rivers and wipe out native fish

- Written by John Harris, Adjunct Associate Professor, Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW

The federal government’s Snowy 2.0 energy venture is controversial for many reasons, but one has largely escaped public attention. The project threatens to devastate aquatic life by introducing predators and polluting important rivers. It may even push one fish species to extinction.

The environmental impact statement for the taxpayer-funded project is almost 10,000 pages long. Yet it fails to resolve critical problems, and in one case seeks legal exemptions to enable Snowy 2.0 to wreak environmental damage.

The New South Wales government is soon expected to grant the project environmental approval. This process should be suspended, and independent experts should urgently review the project’s environmental credentials.

Energy Minister Angus Taylor, left, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison, at the Snowy Hydro scheme.

Lukas Coch/aAAP

Energy Minister Angus Taylor, left, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison, at the Snowy Hydro scheme.

Lukas Coch/aAAP

Native fish extinctions

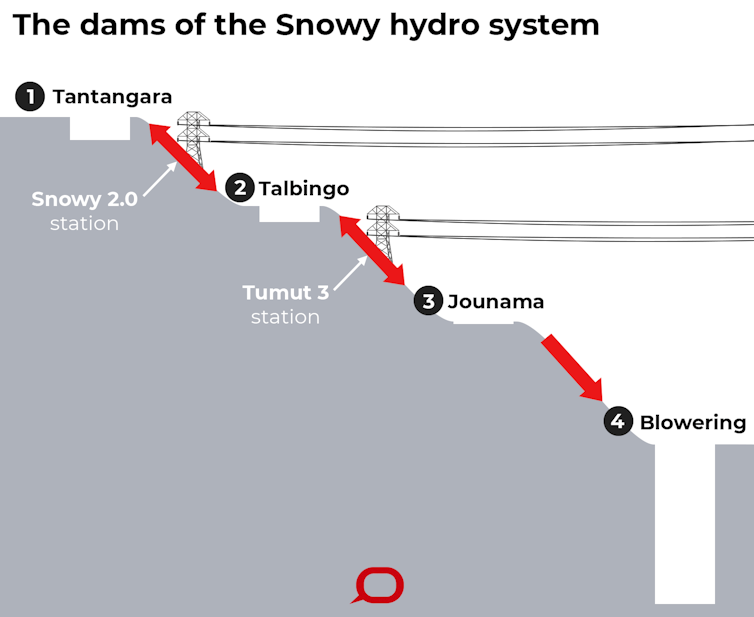

Snowy Hydro Limited, a Commonwealth-owned corporation, is behind the Snowy 2.0 project in the Kosciuszko National Park in southern NSW. It involves building a giant tunnel to connect two water storages – the Tantangara and Talbingo reservoirs. By extension, the project will also connect the rivers and creeks connected to these reservoirs.

A small, critically endangered native fish, the stocky galaxias, lives in a creek upstream of Tantangara. This is the last known population of the species.

Read more: Snowy 2.0 is a wolf in sheep's clothing – it will push carbon emissions up, not down

An invasive native fish, the climbing galaxias, lives in the Talbingo reservoir (it was introduced from coastal streams when the original Snowy project was built). Water pumped from Tantangara will likely transfer this fish to Talbingo.

From here, the climbing galaxias’ capacity to climb wet vertical surfaces would enable it to reach upstream creeks and compete for food with, and prey on, stocky galaxias – probably pushing it into extinction.

The stocky galaxias.

Hugh Allan

The stocky galaxias.

Hugh Allan

Snowy Hydro has applied for an exemption under NSW biosecurity legislation to permit the transfer of the climbing galaxias and two other fish species: the alien, noxious redfin perch and eastern gambusia.

Redfin perch compete for food with other species and produce many offspring. They are voracious, carnivorous predators, known to prey on smaller fish.

Redfin perch also allow the establishment of a fatal fish disease – epizootic haematopoietic necrosis virus – or EHN. This disease kills the endangered native Macquarie perch, the population of which below Tantangara is one of very few remaining.

If Snowy 2.0 is granted approval, it is likely to spread these problematic species through the headwaters of the Murrumbidgee, Snowy and Murray rivers.

The climbing galaxias, which threatens the native stocky galaxias.

Stella McQueen/Wikimedia

The climbing galaxias, which threatens the native stocky galaxias.

Stella McQueen/Wikimedia

Acid and asbestos pollution

Four million tonnes of rock excavated to build Snowy 2.0 would be dumped into the two reservoirs. Snowy Hydro has not assessed the pollution risks this creates. The rock will contain potential acid-forming minerals and a form of asbestos, which threaten to pollute water storages and rivers downstream.

When the first stage of the Snowy Hydro project was built, comparable rocks were dumped in the Tooma River catchment. Research in 2006 suggested the dump was associated with eradication of almost all fish from the Tooma River downstream after rainfall.

Read more: Snowy 2.0 will not produce nearly as much electricity as claimed. We must hit the pause button

Addressing the problems

The environmental impact statement either ignores, or pays inadequate attention to, these environmental problems.

For example, installing large-scale screens at water inlets would be the best way to prevent fish transfer from Talbingo Dam, but Snowy Hydro has dismissed it as too costly.

Snowy Hydro instead proposes a dubious second-rate measure: screens to filter pumped flows leaving Tantangara reservoir, and building a barrier in the stream below the stocky galaxias habitat.

The best and cheapest way to prevent damage from alien species is stopping the populations from establishing. Trying to control or eradicate pest species once they’re established is far more difficult and costly.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

We believe the measures proposed by Snowy Hydro are impractical. It would be very difficult to maintain a screen fine and large enough to prevent fish eggs and larvae moving out of Tantangara reservoir and such screens would be totally ineffective at preventing the spread of EHN virus.

A six metre-high waterfall downstream of the stocky galaxias habitat currently protects the critically endangered species from other invasive species threats. But climbing galaxias have an extraordinary ability to ascend wet surfaces. They would easily climb the waterfall, and possibly the proposed creek barrier as well.

Such an engineered barrier has never been constructed in Australia. We are informed that in New Zealand, the barriers have not been fully effective and often require design adjustments.

Read more:

The government's electricity shortlist rightly features pumped hydro (and wrongly includes coal)

Even if the barrier protected the stocky galaxias at this location, efforts to establish populations in other unprotected regional streams would be severely hampered by the spread of climbing galaxias.

Preventing redfin and EHN from entering the Murrumbidgee River downstream of Tantangara depends on the reservoir never spilling. The reservoir has spilled twice since construction in the 1960s, and would operate at much higher water levels when Snowy 2.0 was operating. Despite this, Snowy Hydro says it has “high confidence in being able to avoid spill”.

If dumped spoil pollutes the two reservoirs and Murrumbidgee and Tumut rivers, this would also have potentially profound ecological impacts. These have not been critically assessed, nor effective prevention methods identified.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

We believe the measures proposed by Snowy Hydro are impractical. It would be very difficult to maintain a screen fine and large enough to prevent fish eggs and larvae moving out of Tantangara reservoir and such screens would be totally ineffective at preventing the spread of EHN virus.

A six metre-high waterfall downstream of the stocky galaxias habitat currently protects the critically endangered species from other invasive species threats. But climbing galaxias have an extraordinary ability to ascend wet surfaces. They would easily climb the waterfall, and possibly the proposed creek barrier as well.

Such an engineered barrier has never been constructed in Australia. We are informed that in New Zealand, the barriers have not been fully effective and often require design adjustments.

Read more:

The government's electricity shortlist rightly features pumped hydro (and wrongly includes coal)

Even if the barrier protected the stocky galaxias at this location, efforts to establish populations in other unprotected regional streams would be severely hampered by the spread of climbing galaxias.

Preventing redfin and EHN from entering the Murrumbidgee River downstream of Tantangara depends on the reservoir never spilling. The reservoir has spilled twice since construction in the 1960s, and would operate at much higher water levels when Snowy 2.0 was operating. Despite this, Snowy Hydro says it has “high confidence in being able to avoid spill”.

If dumped spoil pollutes the two reservoirs and Murrumbidgee and Tumut rivers, this would also have potentially profound ecological impacts. These have not been critically assessed, nor effective prevention methods identified.

The Tumut 3 scheme, part of the existing Snowy Hydro scheme.

Snowy Hydro Ltd

Looking to the future

Snowy 2.0 will likely make one critically endangered species extinct and threaten an important remaining population of another, as well as pollute freshwater habitats. As others have noted, the project is also questionable on other environmental and economic grounds.

These potential failures underscore the need to immediately halt Snowy 2.0, and subject it to independent expert scrutiny.

In response to the issues raised in this article, a spokesperson for Snowy Hydro said:

“Snowy Hydro’s EIS, supported by numerous reports from independent scientific experts, extensively address potential water quality and fish transfer impacts and the risk mitigation measures to be put in place. As the EIS is currently being assessed by the NSW Government we have no further comment.”

The Tumut 3 scheme, part of the existing Snowy Hydro scheme.

Snowy Hydro Ltd

Looking to the future

Snowy 2.0 will likely make one critically endangered species extinct and threaten an important remaining population of another, as well as pollute freshwater habitats. As others have noted, the project is also questionable on other environmental and economic grounds.

These potential failures underscore the need to immediately halt Snowy 2.0, and subject it to independent expert scrutiny.

In response to the issues raised in this article, a spokesperson for Snowy Hydro said:

“Snowy Hydro’s EIS, supported by numerous reports from independent scientific experts, extensively address potential water quality and fish transfer impacts and the risk mitigation measures to be put in place. As the EIS is currently being assessed by the NSW Government we have no further comment.”

Authors: John Harris, Adjunct Associate Professor, Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW