How Australia's response to the Spanish flu of 1919 sounds warnings on dealing with coronavirus

- Written by Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Most Australians - Indigenous people under the protection acts were an exception - have long taken for granted their right to cross state borders. They have treated them much as they do the often unmarked boundaries dividing their suburbs. Not any more.

Australia has closed its international borders to non-residents. South Australia has announced it will close its borders, New South Wales is moving closer to lock-down over the next two days, with Victoria set to follow suit. The Tasmanian government is forcing non-essential travellers into 14 days of quarantine. The Combined Aboriginal Organisations of Alice Springs called for severe restrictions on entry to the Northern Territory, and its government has now followed Tasmania’s example. Queensland has reciprocated by imposing controls on part of its western border.

Indigenous representatives are right to be concerned. The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1919 devastated some Aboriginal communities. There are many other echoes of that crisis of a century ago in the one we face now.

Read more: Grattan on Friday: We are now a nation in self-isolation

COVID-19 represents the worst public health crisis the world has faced since the Spanish flu. Estimates of global deaths from the flu in 1919 vary, often beginning at around 30 million but rising as high as 100 million. Australian losses were probably about 12,000-15,000 deaths.

The outbreak did not originate in Spain, but early reports came from that country, where the Spanish king himself went down with the virus. It happened at the end of the first world war and was intimately connected with that better-known disaster.

The virus likely travelled to Europe with American troops. As the war ended, other soldiers then carried it around the world. The virus would kill many more people than the war itself.

Australia was fortunate in its relatively light death toll; lighter, for instance, than South Africa’s or New Zealand’s.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes was in Europe, at first in London and then at the Paris Peace Conference. But the Commonwealth acted early. The imposition of a strict maritime quarantine in late 1918 and early 1919 helped slow the spread and was decisive in producing a lower rate of infection. But the authorities were ultimately unable to provide a uniform response as the crisis worsened.

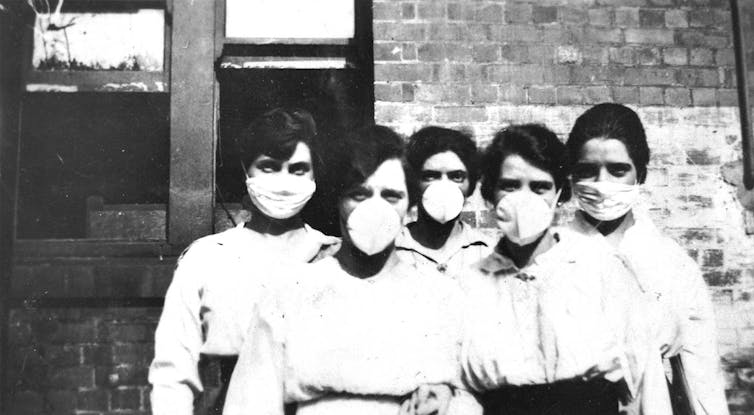

Women wearing surgical masks in Brisbane in 1919.

National Museum of Australia

Women wearing surgical masks in Brisbane in 1919.

National Museum of Australia

Confusion caused by a milder form of influenza that arrived in Australia in September 1918 didn’t help matters. Some authorities, such as the Commonwealth director of quarantine, J.H.L. Cumpston, erroneously believed cases diagnosed in the early months of 1919 were part of this earlier wave. As the historian Anthea Hyslop has shown, having been the architect of the successful maritime quarantine, Cumpston became a victim of his own success. He clung to the theory that new infections were a result of the local epidemic, rather than being a new and more virulent form arriving from overseas.

The Spanish flu came in waves and was extraordinarily virulent. There were reports of people seeming perfectly health at breakfast and dead by evening.

An illness lasting ten or so days, followed by weeks of debility, was more common. An early sign was a chill or shivering, followed by headache and back pain. Eventually, an acute muscle pain would overcome the sufferer, accompanied by some combination of vomiting, diarrhoea, watering eyes, a running or bleeding nose, a sore throat and a dry cough. The skin might acquire a strange blue or plum colour.

Unlike with COVID-19, which has so far had its worst effects on older people, men between the ages of about 20 and 40 seem to have been especially vulnerable. The well-known Victorian socialist and railway union leader, Frank Hyett, seen by some as a future Labor prime minister, lost his life on Anzac Day 1919 at just 37. Five thousand attended his funeral, probably not wise in the circumstances, but testament to his standing.

Almost a third of deaths in Australia were of adults between 25 and 34. The Spanish flu probably infected 2 million Australians in a population of about 5 million. In Sydney alone, 40% of residents caught it.

For Australia, the flu came after a most divisive and traumatic war in which Hyett himself had been a prominent anti-conscriptionist. Many Australians then and now believe the war made the nation. The federation of the colonies had occurred less than two decades before, but it is supposedly the blood sacrifice of war that melded what were still quasi-colonies into a nation in the emotional and spiritual sense. Gallipoli and the Anzac legend are credited with strengthening a national outlook.

Medical staff in Surry Hills, NSW, 1919.

NSW State Archives

Medical staff in Surry Hills, NSW, 1919.

NSW State Archives

But that outlook was hard to discern during the crisis of 1919. In November 1918, the various state authorities had entered into an agreement for dealing with the threat, but it did not long hold. In his groundbreaking social history of the Spanish influenza epidemic, Humphrey McQueen suggested that in relation to many matters, “the Commonwealth of Australia passed into recess”.

“The dislocation of interstate traffic is quite unavoidable,” commented the Tamworth Daily Observer on January 31 1919, “as naturally the clean States could not be expected to continue communications with the infected.”

The flu probably came into the country via returning soldiers, many of whom broke quarantine. The precise source of the first known infection – in Melbourne in January 1919 – was never discovered.

Under the federal agreement, Victorian health authorities should have promptly reported the case to the Commonwealth, which would then have closed the borders with New South Wales and South Australia. Once cases were reported in other states, the Commonwealth would then lift the border controls. As with the rabbit-proof fence ridiculed by Henry Lawson, there was not much point in trying to prevent the border crossing of a disease already on both sides, especially considering the threat to interstate commerce.

It was a cumbersome plan and it did not work. Melbourne authorities did not report its early cases to the Commonwealth. With the delay of a week, the flu reached Sydney by train from Melbourne. Authorities in New South Wales quickly declared that state’s small number of infections a day before a dilatory Victoria reported its much larger number, now over 350.

There were too few doctors and nurses to deal with the crisis – many were still with the armed forces overseas, and others caught the flu. Health facilities were overrun. In Melbourne, the Exhibition Building was turned into a large hospital, as were some schools. Schools shut down at various times in different states during 1919, but widespread disruption was caused either by government decisions to close or the illness of teachers.

National Museum of Australia

Individual states did their own thing as the national agreement fell apart. Tasmania imposed a strict quarantine and had the lowest mortality rate in Australia – 114 per 100,000 – but the pandemic did its economy great damage. Western Australian authorities impounded the transcontinental train and placed its passengers in isolation.

Queensland imposed border control. Travellers had to cool their heels in Tenterfield, in tents and public buildings adapted to house them. There was irony here: this was the town where, in a famous address, Henry Parkes initiated the move toward federation of the colonies in 1889.

Land quarantine was likely ineffective. And while maritime quarantine had almost certainly slowed the rate of infection, its prolongation by the states did great damage to an already fragile economy devastated by the war. Coal was the lifeblood of an industrialising economy, and it was mainly carried by the coastal shipping trade.

There were shortages of other goods, too. Tasmania was running low on flour, and its developing tourism industry was badly knocked about. But such a price was surely worth paying for Australia’s moderate rate of infection and death compared with international standards.

As with COVID-19, doctors bickered about the best way of dealing with the crisis. Newspapers raised alarm with their regular comparisons with the Black Death of medieval times. Advertisements for quack cures abounded, just as dodgy advice – along with plenty of good sense – can be found at a glance on social media today.

Read more:

100 years later, why don't we commemorate the victims and heroes of 'Spanish flu'?

Inoculation was widely practised and might have had a positive effect on those not yet infected. For a time, it was compulsory to wear a mask in the street. Places of entertainment such as theatres, cinemas and dance halls closed, as did churches. The Sydney Easter Show was called off in 1919, as it has been for 2020.

Some good came of the crisis. The formation of a federal Department of Health in 1921 was a response to the failure of the states to cooperate.

But there are also plenty of warnings for us in the Spanish flu pandemic. Some thought the crisis under control early in the autumn of 1919, with state governments lifting some restrictions. But it came to life again and carried off many Australians with it.

The Spanish flu might have hit working-age men most seriously because they were more likely than others to have multiple social contacts. Vulnerable communities such as Indigenous people were very badly affected.

And Australia at times suffered from deficiencies of political, medical and administrative decision-making.

The recent move by Tasmania, and the announcements over the weekend that other state premiers are moving beyond the nationally agreed restrictions on activity, might presage future divisions between Australian governments.

National Museum of Australia

Individual states did their own thing as the national agreement fell apart. Tasmania imposed a strict quarantine and had the lowest mortality rate in Australia – 114 per 100,000 – but the pandemic did its economy great damage. Western Australian authorities impounded the transcontinental train and placed its passengers in isolation.

Queensland imposed border control. Travellers had to cool their heels in Tenterfield, in tents and public buildings adapted to house them. There was irony here: this was the town where, in a famous address, Henry Parkes initiated the move toward federation of the colonies in 1889.

Land quarantine was likely ineffective. And while maritime quarantine had almost certainly slowed the rate of infection, its prolongation by the states did great damage to an already fragile economy devastated by the war. Coal was the lifeblood of an industrialising economy, and it was mainly carried by the coastal shipping trade.

There were shortages of other goods, too. Tasmania was running low on flour, and its developing tourism industry was badly knocked about. But such a price was surely worth paying for Australia’s moderate rate of infection and death compared with international standards.

As with COVID-19, doctors bickered about the best way of dealing with the crisis. Newspapers raised alarm with their regular comparisons with the Black Death of medieval times. Advertisements for quack cures abounded, just as dodgy advice – along with plenty of good sense – can be found at a glance on social media today.

Read more:

100 years later, why don't we commemorate the victims and heroes of 'Spanish flu'?

Inoculation was widely practised and might have had a positive effect on those not yet infected. For a time, it was compulsory to wear a mask in the street. Places of entertainment such as theatres, cinemas and dance halls closed, as did churches. The Sydney Easter Show was called off in 1919, as it has been for 2020.

Some good came of the crisis. The formation of a federal Department of Health in 1921 was a response to the failure of the states to cooperate.

But there are also plenty of warnings for us in the Spanish flu pandemic. Some thought the crisis under control early in the autumn of 1919, with state governments lifting some restrictions. But it came to life again and carried off many Australians with it.

The Spanish flu might have hit working-age men most seriously because they were more likely than others to have multiple social contacts. Vulnerable communities such as Indigenous people were very badly affected.

And Australia at times suffered from deficiencies of political, medical and administrative decision-making.

The recent move by Tasmania, and the announcements over the weekend that other state premiers are moving beyond the nationally agreed restrictions on activity, might presage future divisions between Australian governments.

Authors: Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University