The jobs market is nowhere near as good as you've heard, and it's changing us

- Written by Michael Keating, Visiting Fellow, College of Business & Economics, Australian National University

We are continually being told that more of us are employed than ever before.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe points out (correctly) that a higher proportion of us are in jobs than at any other time. Prime Minister Scott Morrison says an extra 1.5 million Australians have found jobs since the Coalition took office, 260,000 of them in the past year.

Yet in many ways the job market is weak, as unusually low wage growth and an uncommon reluctance to change jobs make clear.

A deeper look into the statistics provides clues as to why.

First, many of the extra jobs created have been part-time.

Part-time work, service industries

Over the life of the Coalition government between 2013 and 2019, total employment grew at an annual rate of 2% but the total hours worked increased at an annual rate of only 1.1% – that’s about half the rate of 1.9% that hours grew during the Hawke/Keating Labor era.

It means the underemployment rate hasn’t come down as much as the unemployment rate.

In fact, it has risen. The proportion of workers who are underemployed – who would like to work more hours than they do – has climbed from 7.9% to 9.1% during the life of the Coalition government.

Over the same period the unemployment rate has fallen only a few points, from 5.7 to 5.3%.

Read more: Jobs but not enough work. How power keeps workers anxious and wages low

The few industries in which hours worked have increased faster than the average have been mainly service industries, more likely than others to employ women.

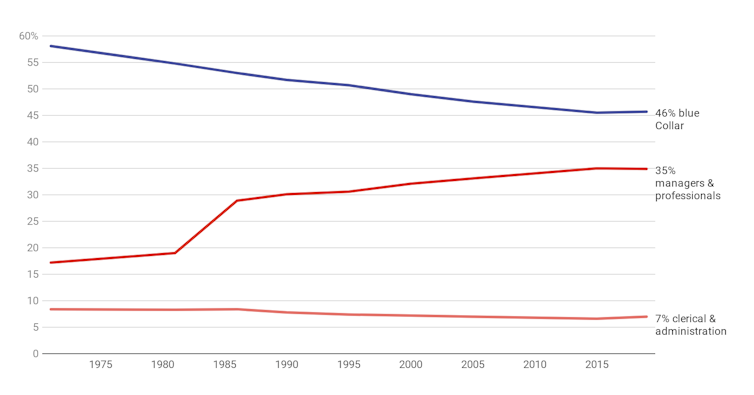

The change in the distribution of industries has also been reflected in the a change in the distribution of occupations.

For both men and women, the proportion in blue collar, clerical and sales jobs has fallen over time.

Type of occupation by share of employment, men

(Shares of community & personal service and sales are each under 10%)

Source: Bell & Keating, Fair Share, ABS 6291.0.55.003

(Shares of community & personal service and sales are each under 10%)

Source: Bell & Keating, Fair Share, ABS 6291.0.55.003

The share of jobs that do not require a university degree has consequently fallen. The share that require higher skills has risen.

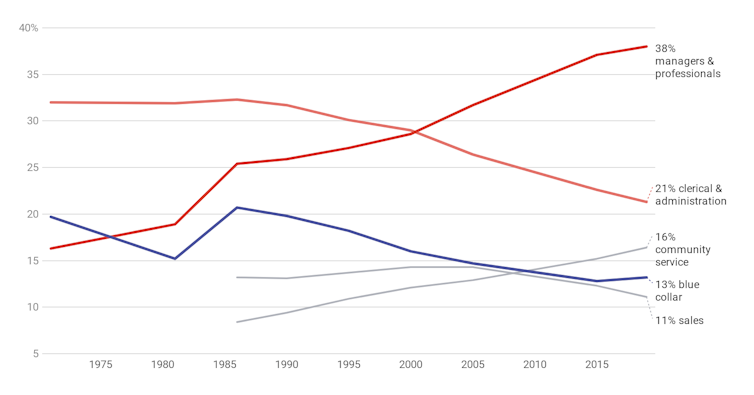

By and large, these changes in the distribution of jobs by industry and occupation and the growth of part-time opportunities has tended to favour women.

Type of occupation by share of employment, women

Blue collar includes technicians and trades, machinery operators and drivers and labourers.

Source: Bell & Keating, Fair Share, ABS 6291.0.55.003

Blue collar includes technicians and trades, machinery operators and drivers and labourers.

Source: Bell & Keating, Fair Share, ABS 6291.0.55.003

Many men now find themselves in jobs that don’t have good growth prospects.

It means that their job security is less than in the past and their bargaining power for higher wages is less than in the past.

In sum, the skewed distribution in where the jobs are being created suggests that many Australians, particularly men, are missing out. Highly educated men (and women) can still get good jobs, but in most industries and occupations, prospects are stagnating.

Risk averse workers

A likely consequence is that workers, and perhaps especially male workers, have become less keen to take risks, including the risk of asking to be paid more.

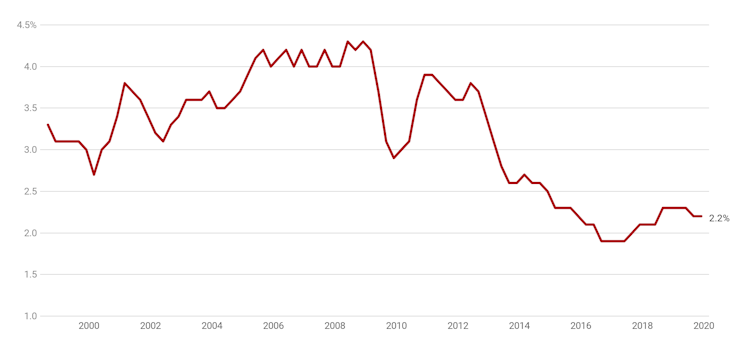

Another risk is attempting to change jobs. Job-switching typically leads to higher pay – not only for those who switch, but also, to a lesser extent, for those who stay as higher pay flows through.

Recent treasury research found that job-switching rates fell by about 2 percentage points between 2003 and 2015 (the end-date of its data). It is very likely to have fallen since.

The treasury research found that each 1 percentage point decline in job-switching was associated with a ½ percentage point decline in average annual wage growth – meaning the decline of 2 percentage points or more would account for a substantial part of the recent decline.

Wage growth, annual

Annual change in total hourly rates of pay excluding bonuses.

Source: ABS 6345.0

Annual change in total hourly rates of pay excluding bonuses.

Source: ABS 6345.0

Broad implications

The less fluid and less dynamic labour market might also be impacting the transmission of technological change and productivity growth.

Adoption of new technologies accelerates when workers switch to the most productive firms.

The treasury finds that the difference in employment growth between high and low productivity firms has fallen by 1½ percentage points since 2012, the point at which productivity growth began to slow.

And declining confidence about job prospects might also be affecting political attitudes.

Read more: You are what you vote: the social and demographic factors that influence your vote

Today, the Labor Party no longer has the exclusive loyalty of workers. Instead, ever since John Howard targeted and gained the support of “tradies”, the Coalition has increasingly sought support from workers who feel less secure, both about their own jobs and also about the future more broadly.

Often these people respond to what they see as a loss of security and status by attaching themselves to strong leaders. They can become loyal to inherited values, and can be hostile to outsiders or change, viewing them as challenges to inherited values. They can mistrust experts, especially when the advice of those experts clashes with their inherited beliefs and what they see as their traditional way of life.

It is possible that Morrison won the last election because (like Trump) he appealed to people who felt they have lost security and status, and opposed change. He offered reassurance, partly because of his style, but also because of his resistance to change.

If Labor is to become competitive, it needs to develop policies that will restore confidence among workers that they have a good future. It isn’t an impossible task.

Authors: Michael Keating, Visiting Fellow, College of Business & Economics, Australian National University