Friday essay: George Eliot 200 years on

- Written by Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

Mary Ann Evans took the pseudonym “George Eliot” because she wanted to be taken seriously as a writer.

Other female authors – Maria Edgeworth and Jane Austen, for example – had penned work under their own names, but Evans feared that if her identity was discovered her books would be dismissed as “light” and “sentimental”.

Astonishingly, in an age of patriarchy, this was not the case.

Eliot’s reputation has grown steadily in the 200 years since her birth. And her Middlemarch (1871-2) is often claimed to be the greatest novel in the English language.

Eliot’s “incognito” was shattered shortly after her first bestselling novel, Adam Bede, was published in 1859. Critics were left marvelling not only that the author they collectively imagined to be a kindly country clergyman was a woman, but also that she was an atheist living openly with another woman’s husband.

In an age in which few women were educated or owned property, and few middle class women engaged in paid employment, Eliot overcame every obstacle.

She lived a scandalous life by Victorian standards. But she was one of Queen Victoria’s favourite writers.

And in the thousands of words that were to spill across the pages of the literary quarterlies about Eliot’s books, there was far less interest in salacious gossip than in the question of whether she had drawn a picture of the world as it “really” was.

No matter how much these 19th century - mostly male - critics attacked Eliot’s novels for their political and cultural heresies, it was obvious – indeed, astonishing – that they took them seriously as fundamentally important works.

A ‘great, horse-faced bluestocking’

Born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, on November 22, 1819, the third daughter of Robert and Christiana Evans, Eliot was afforded the sort of education not usually granted to women in this period. She was not considered physically attractive, and her father believed this would severely limit her prospects of marriage.

Eliot’s “incognito” was shattered shortly after her first bestselling novel, Adam Bede, was published in 1859. Critics were left marvelling not only that the author they collectively imagined to be a kindly country clergyman was a woman, but also that she was an atheist living openly with another woman’s husband.

In an age in which few women were educated or owned property, and few middle class women engaged in paid employment, Eliot overcame every obstacle.

She lived a scandalous life by Victorian standards. But she was one of Queen Victoria’s favourite writers.

And in the thousands of words that were to spill across the pages of the literary quarterlies about Eliot’s books, there was far less interest in salacious gossip than in the question of whether she had drawn a picture of the world as it “really” was.

No matter how much these 19th century - mostly male - critics attacked Eliot’s novels for their political and cultural heresies, it was obvious – indeed, astonishing – that they took them seriously as fundamentally important works.

A ‘great, horse-faced bluestocking’

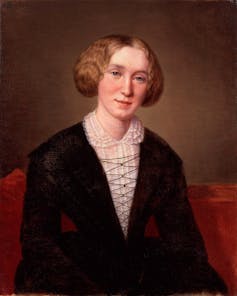

Born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, on November 22, 1819, the third daughter of Robert and Christiana Evans, Eliot was afforded the sort of education not usually granted to women in this period. She was not considered physically attractive, and her father believed this would severely limit her prospects of marriage.

Eliot’s father believed her looks would limit her marriage prospects.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1850, Eliot – then calling herself Marian Evans – moved from Coventry to London, determined to become a writer.

Just a few years before, she had published her English translation of David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined. Notoriously, Strauss argued that the “miracles” of the New Testament were myths and fabrications. The Earl of Shaftesbury promptly castigated Eliot’s translation as “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell”.

Eliot took up residence in the house of the radical publisher John Chapman, who appointed her assistant editor of the Westminster Review. She was deeply influenced by John Stuart Mill, particularly his groundbreaking essay on gender equality, Subjection of Women.

She sympathised with the 1848 revolutions on the continent. She held great hopes for women’s education. She supported female suffrage.

At this time, Eliot formed a series of attachments to married men, including Chapman and Herbert Spencer, before meeting the critic George Henry Lewes, with whom she shared a committed, life-long relationship.

Eliot’s father believed her looks would limit her marriage prospects.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1850, Eliot – then calling herself Marian Evans – moved from Coventry to London, determined to become a writer.

Just a few years before, she had published her English translation of David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined. Notoriously, Strauss argued that the “miracles” of the New Testament were myths and fabrications. The Earl of Shaftesbury promptly castigated Eliot’s translation as “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell”.

Eliot took up residence in the house of the radical publisher John Chapman, who appointed her assistant editor of the Westminster Review. She was deeply influenced by John Stuart Mill, particularly his groundbreaking essay on gender equality, Subjection of Women.

She sympathised with the 1848 revolutions on the continent. She held great hopes for women’s education. She supported female suffrage.

At this time, Eliot formed a series of attachments to married men, including Chapman and Herbert Spencer, before meeting the critic George Henry Lewes, with whom she shared a committed, life-long relationship.

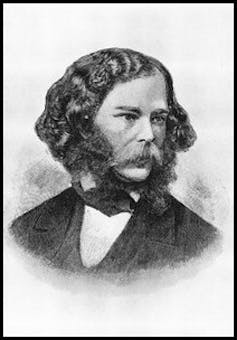

George Henry Lewes (1817-1878)

Wikimedia Commons

Lewes was married to Agnes Jervis, with whom he had three children. Unlike other unconventional literary liaisons of the period, Lewes and Eliot did not keep their relationship a secret.

Like so many other men, Lewes was drawn to the luminosity of Eliot’s intelligence. She had an awesome curiosity, an endless appetite for ideas.

Henry James famously characterised her as “magnificently ugly, deliciously hideous”.

And yet in his snarky, entitled way he also marvelled at his reaction to the force of Eliot’s personality. “Behold me, literally in love with this great horse-faced bluestocking!”

Her practical humanism

In 1854, Eliot translated Ludwig Feurerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, in which he declared God to be a figment of the human imagination. Instead, he wanted to think about what he called “species being” – that is, to consider what it means to think from the standpoint of being human, of being part of the wider social fabric.

Feurerbach’s ideas were fundamental in shaping the practical humanism that forms the beating heart of Eliot’s novels.

Eliot’s social consciousness, her vivid critiques of capitalism, are keenly displayed in her 1861 novel about a linen weaver, Silas Marner, and her 1876 masterpiece Daniel Deronda - a sprawling tale about a fatally self-absorbed heroine, Gwendolen Harleth, and the easy, ingrained prejudice of British society against the Jews.

Trailer for the television adaptation of Daniel Deronda.But it is their capaciousness - perhaps - that is the real theme of Eliot’s books. Her novels are held together by elaborate patterns of imagery, threads of gossip, networks of feeling and connection, linking character to character.

Background scenes of the social world are interwoven with the deeper dimensions of private life and even the fabric of human consciousness, so the novelistic structure reflects the fragile, web-like ties that hold society together.

Her characters’ motivations may be ego-satisfying, self-deceiving, or concealed, even from themselves, or all of these at once. And the tangled paradoxes they encounter as they journey through their novelistic worlds force readers to reassess themselves and their perspectives.

Nobody, in short, does honesty or frailty quite like Eliot. If you read her work, and really pay attention, you will likely find out things about yourself you didn’t know, and maybe would rather not.

As Virginia Woolf famously declared of Middlemarch, it is “one of the few English novels written for grown up people”.

George Henry Lewes (1817-1878)

Wikimedia Commons

Lewes was married to Agnes Jervis, with whom he had three children. Unlike other unconventional literary liaisons of the period, Lewes and Eliot did not keep their relationship a secret.

Like so many other men, Lewes was drawn to the luminosity of Eliot’s intelligence. She had an awesome curiosity, an endless appetite for ideas.

Henry James famously characterised her as “magnificently ugly, deliciously hideous”.

And yet in his snarky, entitled way he also marvelled at his reaction to the force of Eliot’s personality. “Behold me, literally in love with this great horse-faced bluestocking!”

Her practical humanism

In 1854, Eliot translated Ludwig Feurerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, in which he declared God to be a figment of the human imagination. Instead, he wanted to think about what he called “species being” – that is, to consider what it means to think from the standpoint of being human, of being part of the wider social fabric.

Feurerbach’s ideas were fundamental in shaping the practical humanism that forms the beating heart of Eliot’s novels.

Eliot’s social consciousness, her vivid critiques of capitalism, are keenly displayed in her 1861 novel about a linen weaver, Silas Marner, and her 1876 masterpiece Daniel Deronda - a sprawling tale about a fatally self-absorbed heroine, Gwendolen Harleth, and the easy, ingrained prejudice of British society against the Jews.

Trailer for the television adaptation of Daniel Deronda.But it is their capaciousness - perhaps - that is the real theme of Eliot’s books. Her novels are held together by elaborate patterns of imagery, threads of gossip, networks of feeling and connection, linking character to character.

Background scenes of the social world are interwoven with the deeper dimensions of private life and even the fabric of human consciousness, so the novelistic structure reflects the fragile, web-like ties that hold society together.

Her characters’ motivations may be ego-satisfying, self-deceiving, or concealed, even from themselves, or all of these at once. And the tangled paradoxes they encounter as they journey through their novelistic worlds force readers to reassess themselves and their perspectives.

Nobody, in short, does honesty or frailty quite like Eliot. If you read her work, and really pay attention, you will likely find out things about yourself you didn’t know, and maybe would rather not.

As Virginia Woolf famously declared of Middlemarch, it is “one of the few English novels written for grown up people”.

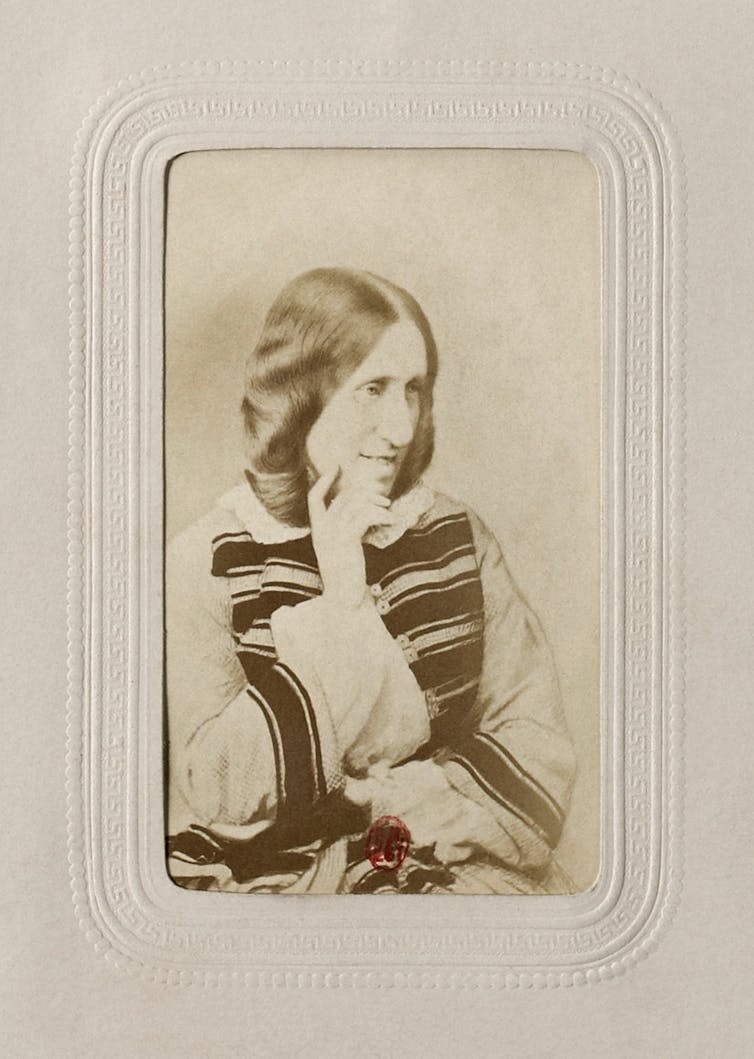

A photographic portrait (albumen print) of George Eliot circa 1865.

Wikimedia Commons

Middlemarch - the greatest novel in the English language

Middlemarch was published serially in eight parts at two monthly intervals from December 1871. It went on sale in December 1872 as four volumes for two guineas, selling 8,500 copies. But it was only when the cheap edition went on sale in 1874 that the novel found its real audience, selling another 31,000 copies by 1878.

The story - like those found in all Eliot’s novels - is multifaceted. It revolves mostly around Dorothea Brooke, an heiress who makes a terrible marriage to Edward Casaubon, a dusty clergyman, and the character of Tertius Lydgate, a London-trained doctor who wants to bring modern medicine to the Midlands, but chooses an unsuitable wife.

Trailer for the BBC adaptation of Middlemarch.But the deeper theme of Middlemarch is the moral drama around the interaction between character and social environment that is fundamental to contemporary appreciations of 19th century realism – but was often merely puzzling to Victorian critics.

They loved the scale of the novel’s social panorama, “like a portrait gallery” that has been “photographed from the life”; they even came to see that it had, as the Times put it, a “philosophical power”. But they did not immediately grasp that it was Eliot’s most important book. They bemoaned it was not as “delightful” as Adam Bede, her earlier bucolic tale about - among other things - seduction, infanticide, class and education.

In Middlemarch, Dorothea has money; unlike in Austen, there is no threat of penury hanging over her head. Indeed, there is no need for her to marry at all. And yet she does.

She has freedom, up to a point. But her largeness of soul is circumscribed by narrowness of opportunity. Nor is provincial society entirely to blame. Dorothea yearns to do something; to achieve something; but she knows not what. This is her - and our own - tragedy.

When Dorothea, in all her married misery, is confronted by an extraordinary vision of a suffering human society, we encounter one of the most heartbreakingly beautiful passages in Eliot’s ouevre. She writes,

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

This is the anguish that lurks in dark corners of Eliot’s novels – it is the measure of her greatness, and of our struggle to read her.

Dorothea’s quest for a substantial and meaningful life has resonated with the sensibilities of successive generations of feminists. How is she to achieve something? Where should she put her energies? How can she affect the lives of others?

We are all of us “Dorotheas”; all tragically yearning for something. As Virginia Woolf put it, Dorothea and the rest of Eliot’s heroines feel “a demand for something — they scarcely know what — for something that is perhaps incompatible with the facts of human existence.”

A photographic portrait (albumen print) of George Eliot circa 1865.

Wikimedia Commons

Middlemarch - the greatest novel in the English language

Middlemarch was published serially in eight parts at two monthly intervals from December 1871. It went on sale in December 1872 as four volumes for two guineas, selling 8,500 copies. But it was only when the cheap edition went on sale in 1874 that the novel found its real audience, selling another 31,000 copies by 1878.

The story - like those found in all Eliot’s novels - is multifaceted. It revolves mostly around Dorothea Brooke, an heiress who makes a terrible marriage to Edward Casaubon, a dusty clergyman, and the character of Tertius Lydgate, a London-trained doctor who wants to bring modern medicine to the Midlands, but chooses an unsuitable wife.

Trailer for the BBC adaptation of Middlemarch.But the deeper theme of Middlemarch is the moral drama around the interaction between character and social environment that is fundamental to contemporary appreciations of 19th century realism – but was often merely puzzling to Victorian critics.

They loved the scale of the novel’s social panorama, “like a portrait gallery” that has been “photographed from the life”; they even came to see that it had, as the Times put it, a “philosophical power”. But they did not immediately grasp that it was Eliot’s most important book. They bemoaned it was not as “delightful” as Adam Bede, her earlier bucolic tale about - among other things - seduction, infanticide, class and education.

In Middlemarch, Dorothea has money; unlike in Austen, there is no threat of penury hanging over her head. Indeed, there is no need for her to marry at all. And yet she does.

She has freedom, up to a point. But her largeness of soul is circumscribed by narrowness of opportunity. Nor is provincial society entirely to blame. Dorothea yearns to do something; to achieve something; but she knows not what. This is her - and our own - tragedy.

When Dorothea, in all her married misery, is confronted by an extraordinary vision of a suffering human society, we encounter one of the most heartbreakingly beautiful passages in Eliot’s ouevre. She writes,

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

This is the anguish that lurks in dark corners of Eliot’s novels – it is the measure of her greatness, and of our struggle to read her.

Dorothea’s quest for a substantial and meaningful life has resonated with the sensibilities of successive generations of feminists. How is she to achieve something? Where should she put her energies? How can she affect the lives of others?

We are all of us “Dorotheas”; all tragically yearning for something. As Virginia Woolf put it, Dorothea and the rest of Eliot’s heroines feel “a demand for something — they scarcely know what — for something that is perhaps incompatible with the facts of human existence.”

Authors: Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia