How we feel about our cars means the road to a driverless future may not be smooth

- Written by Raul A. Barreto, Senior Lecturer, University of Adelaide

There is a reasonable expectation that autonomous vehicles will dominate the future of transport. Utopian visions suggest these driverless vehicles will lead to dramatic changes to our cities and their transportation.

Autonomous vehicles operating on a network would allow traffic to move safely and seamlessly through cities. They would use less space per vehicle. Traffic flow would be unhindered by traffic lights or other traditional driver signals.

More efficient transportation would use less fuel. Urban spaces could be repurposed as parking needs virtually disappear.

But this utopian vision depends on a range of factors. In particular, these predictions largely rely on how current car drivers respond to the advent of autonomous vehicles.

Our research suggests people’s attitudes to driving and their cars could limit the predicted benefits to traffic flow and city efficiency, at least during the initial transition to driverless vehicles.

What did the research look at?

The research uses the city of Adelaide as a test case. We surveyed commuter preferences for the acceptance and use of driverless vehicles, as compared with their current preferences.

We then developed two scenarios. One is for the medium to long term, when vehicles are fully autonomous. The other is for the short-term transitional phase, during which a mix of conventional and driverless vehicles share the roads.

Using traffic-flow data for Adelaide, we analysed the implications of a shift towards driverless vehicles for:

- traffic flow

- the number of vehicles needed to service commuter demands

- parking

- broader land use in the city centre.

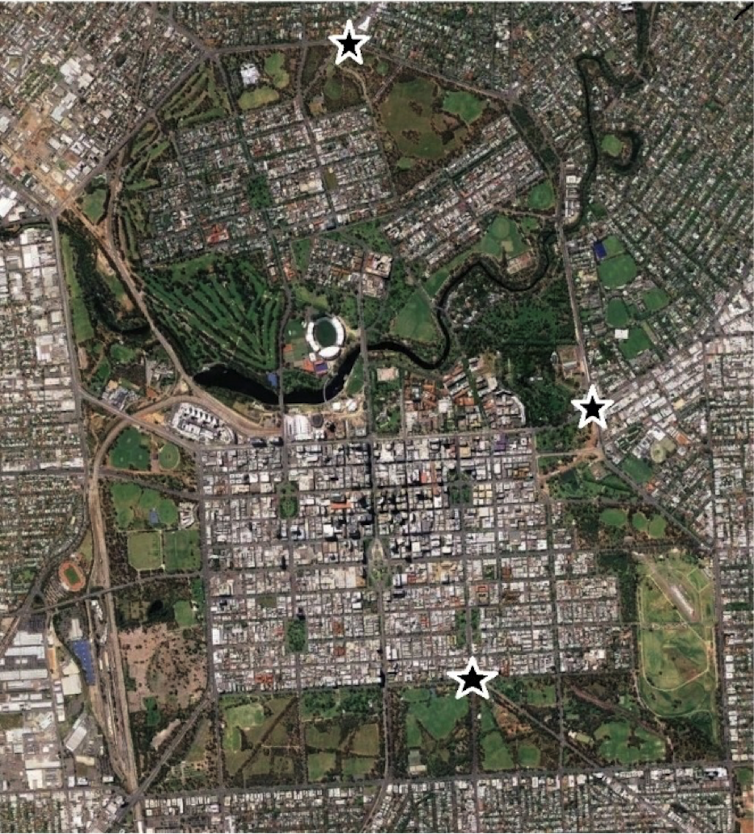

Adelaide is unusual, as a result of its history as a planned city, in having a discrete number of entry and exit points. This allows us to map more accurately average daily traffic flows into and out of the city centre.

Our analysis focuses on three of the city’s gateways, as shown below.

The three Adelaide city gateways analysed for the research.

Google Earth, Author provided

The three Adelaide city gateways analysed for the research.

Google Earth, Author provided

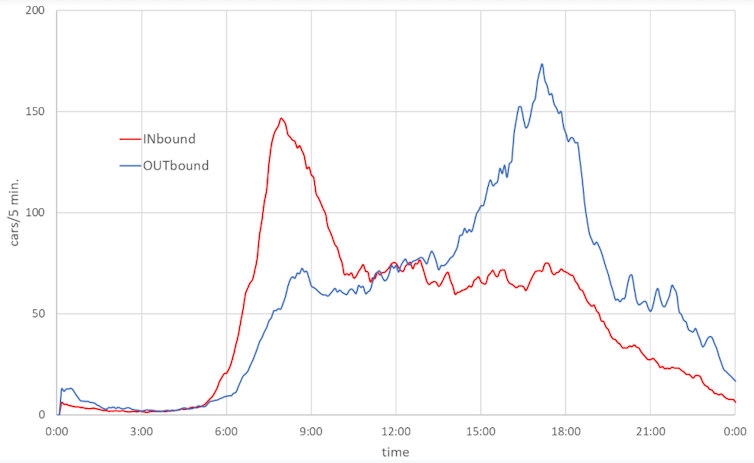

We measured flows through these intersections on a typical day. Using minute-by-minute real-time data, monitored at traffic signals, we created a picture of typical traffic flows into and out of the CBD.

Traffic flows at gateway site into and out of Adelaide city (Unley Rd/South Terrace).

Adelaide City Council, Author provided

Traffic flows at gateway site into and out of Adelaide city (Unley Rd/South Terrace).

Adelaide City Council, Author provided

We also surveyed commuters to discern their current transport preferences versus their perceptions of the hypothetical future.

Combining this information, we then describe possible outcomes of the transition to automated vehicles.

What did the survey find?

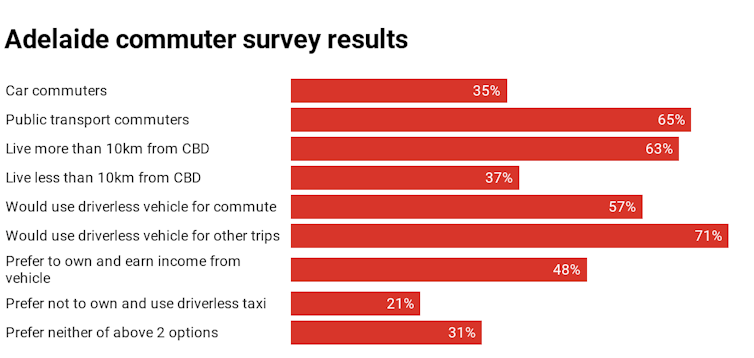

Below is a summary of the survey of a representative sample of 526 regular commuters into the Adelaide CBD.

Data: How Might Autonomous Vehicles Impact the City?, Author provided

We queried respondents’ willingness to carshare by taking advantage of common knowledge of real-world company Uber.

We also investigated respondents’ attitudes by positing a scenario in which driverless vehicles are the norm and conventional driving is a luxury. We assessed likely resistance to autonomous vehicles by considering their willingness to pay to continue to drive traditional vehicles in this scenario.

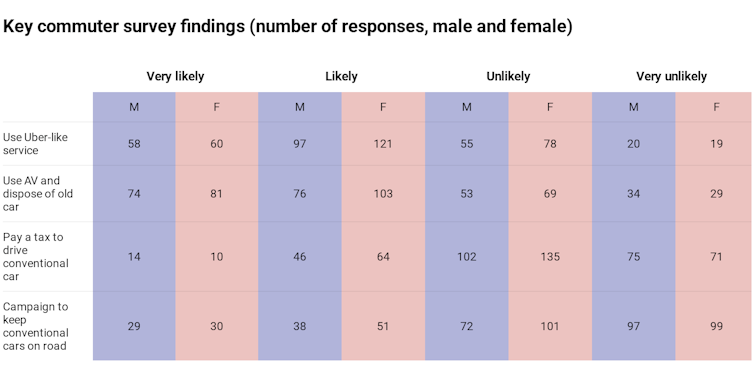

Key results are shown below.

Data: How Might Autonomous Vehicles Impact the City?, Author provided

We queried respondents’ willingness to carshare by taking advantage of common knowledge of real-world company Uber.

We also investigated respondents’ attitudes by positing a scenario in which driverless vehicles are the norm and conventional driving is a luxury. We assessed likely resistance to autonomous vehicles by considering their willingness to pay to continue to drive traditional vehicles in this scenario.

Key results are shown below.

Data: How Might Autonomous Vehicles Impact the City?, Author provided

Attitudes and costs will shape transition

Two observations flow from the responses.

First, it seems likely drivers’ prevailing attitudes to vehicle ownership may be influencing their attitudes to autonomous vehicles. For many, their car represents a status symbol. They feel a strong personal attachment to it.

Second, cost may be a crucial factor in take-up of driverless vehicles. As costs fall, most commuters might bow to financial pressure to shift to autonomous vehicles. However, a minority might lobby to keep a mix of driverless and conventional vehicles on the road.

Our analysis suggests Adelaide could reduce its current vehicle fleet by as much as 76% in the utopian driverless future. This is due to current high car dependence and long commuting times and distances at peak periods.

Yet some predicted benefits, notably the very large reduction in vehicle numbers and better traffic flows, might not be achieved in the near to medium term. This is due to uncertainty about how the transition to a totally driverless city will be achieved and how long it will take.

Key factors are commuter attitudes to driving and autonomous vehicles, the price of the technology, and consumer attitudes to car sharing. Attitudes to car ownership and driving appear to be central to how the transition will play out.

The survey suggests the pleasure of driving themselves, which a substantial minority of Adelaide drivers are unwilling to forgo, could limit the benefits that much of the academic literature optimistically predicts.

Public transport may also be adversely affected as riders switch to driverlesss vehicles. This shift could increase vehicle flows in peak periods, making congestion worse during the transition to complete adoption.

We support the oft-suggested argument that large-scale adoption of driverless vehicles risks stimulating an increase in urban sprawl. In the city centre, parking demand is likely to reduce greatly, allowing more diverse land uses and intensification of economic activity. But parking outside the CBD might increase, as driverless vehicles need not park near their users’ or owners’ workplace, at the expense of amenity.

Our analysis strongly suggests urban policy will be needed to counter the potential negative effects of introducing driverless vehicles.

Data: How Might Autonomous Vehicles Impact the City?, Author provided

Attitudes and costs will shape transition

Two observations flow from the responses.

First, it seems likely drivers’ prevailing attitudes to vehicle ownership may be influencing their attitudes to autonomous vehicles. For many, their car represents a status symbol. They feel a strong personal attachment to it.

Second, cost may be a crucial factor in take-up of driverless vehicles. As costs fall, most commuters might bow to financial pressure to shift to autonomous vehicles. However, a minority might lobby to keep a mix of driverless and conventional vehicles on the road.

Our analysis suggests Adelaide could reduce its current vehicle fleet by as much as 76% in the utopian driverless future. This is due to current high car dependence and long commuting times and distances at peak periods.

Yet some predicted benefits, notably the very large reduction in vehicle numbers and better traffic flows, might not be achieved in the near to medium term. This is due to uncertainty about how the transition to a totally driverless city will be achieved and how long it will take.

Key factors are commuter attitudes to driving and autonomous vehicles, the price of the technology, and consumer attitudes to car sharing. Attitudes to car ownership and driving appear to be central to how the transition will play out.

The survey suggests the pleasure of driving themselves, which a substantial minority of Adelaide drivers are unwilling to forgo, could limit the benefits that much of the academic literature optimistically predicts.

Public transport may also be adversely affected as riders switch to driverlesss vehicles. This shift could increase vehicle flows in peak periods, making congestion worse during the transition to complete adoption.

We support the oft-suggested argument that large-scale adoption of driverless vehicles risks stimulating an increase in urban sprawl. In the city centre, parking demand is likely to reduce greatly, allowing more diverse land uses and intensification of economic activity. But parking outside the CBD might increase, as driverless vehicles need not park near their users’ or owners’ workplace, at the expense of amenity.

Our analysis strongly suggests urban policy will be needed to counter the potential negative effects of introducing driverless vehicles.

Authors: Raul A. Barreto, Senior Lecturer, University of Adelaide