Can Ne Zha, the Chinese superhero with $1b at the box office, teach us how to raise good kids?

- Written by Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University

There is a new challenger to Disney’s hold on the global animation industry, and he is a Chinese demon child.

Ne Zha: Birth of the Demon Child, from Chengdu Coco Cartoon, tells the story of an unlikely hero. Released in China in July, and in Australia, New Zealand, and North America in August, the film has made over CN¥4.97 billion (A$1.02 billion) at the box office.

It has set box-office records for non-English language and non-US animated films, and is the second-highest-grossing Chinese film ever.

But Ne Zha is much more than a cinema phenomenon: this children’s film has a surprising story to tell about contemporary parenting and citizenship in China.

Stories from literature

Animation in China began in the 1920s, and experienced a golden age in the 50s and 60s, coming to an end with the onset of the Cultural Revolution.

This century has seen increased funding for Chinese filmmakers. With stronger state support, animation is predicted to grow and films like Ne Zha that draw from Chinese literature are increasingly popular.

Directed by Jiaozi, the screenplay is loosely based on the 16th-century novel Fengshen Yanyi (Investiture of the Gods), a fantasy story of how the righteous King Wu defeats the ruler of the Shang dynasty.

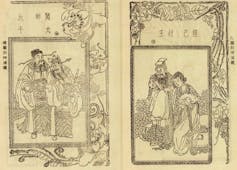

Illustrations from Fengshen Yanyi.

Wikimedia Commons

Illustrations from Fengshen Yanyi.

Wikimedia Commons

Ne Zha is a rebellious boy with supernatural powers who wreaks destruction. When his parents are faced with celestial punishment for his behaviour, Ne Zha takes his own life to save them. With the help of his mentor, Ne Zha is reincarnated as a boy-god and fights for King Wu.

This movie is not the first to draw upon this character: he appeared in the 1979 animation Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King and the 2003-2004 children’s TV series, The Legend of Nezha. But unlike previous adaptations, which focus on Ne Zha’s suicide as an act of self sacrifice, Jiaozi’s film encourages young people to be masters of their own fate.

Anxieties about raising a ‘good’ child

Bad-tempered and foul-mouthed, Ne Zha is uncontrollable. His parents are anxious because he doesn’t conform to expectations of the ideal guai child.

Loosely translated as “good”, guai is a cultural concept that includes ideals of obedience, sensibility, and academic achievement. This centuries-old concept guides parenting in Chinese communities around the world.

Our research into film and TV representations of Chinese childhood shows guai carries mixed meanings. Chinese parents encourage guai children to be “useful” and contribute to their families, communities, and nation. At the same time, they require children to make their own decisions. Children should be obedient but also make sensible choices.

Ne Zha’s parents want their son to be guai. They argue about how they should raise him. Eventually, they trick Ne Zha into training with a mentor to become a demon-slayer like them. They want him to learn self-control and redeem himself.

Ne Zha’s parents want him to learn self-control and become a useful person.

Chengdu Coco Cartoon

Ne Zha’s parents want him to learn self-control and become a useful person.

Chengdu Coco Cartoon

Ne Zha’s parents hope his mentor can tame their son. This desire echoes Chinese parents’ belief education can guide their children into moral and successful citizens.

In mainland China, child-rearing has become increasingly complex. Parents want their children to prosper in a highly competitive and consumption-driven society, but still feel the need to instil moral values in their children.

They worry about raising children who lack important life skills. Psychologist Wu Zhihong controversially claims adults in China are “giant babies”: they don’t know how to take care of themselves and have trouble distinguishing between good and bad.

Like Ne Zha’s parents, the question of how to raise a “good” child looms large in the minds of Chinese parents. The rhetoric used by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reflects a similar desire.

Raising ‘good’ citizens for the state

People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the CCP, upholds Ne Zha as a role model. It urges readers to be enterprising and persistent like him. This signals the party-state wishes to cultivate guai citizens who will contribute to China’s efforts to become a global player.

The irony is, in order to save his village, Ne Zha has to defy authority: the film’s message about what it means to be guai differs from the CCP’s interpretation. Ne Zha refuses to be bound by his fate. He decides to take matters into his own hands to demonstrate there is more than one way to contribute to one’s family and community. Despite Ne Zha’s flaws, he is ultimately a guai child.

Ne Zha’s choices point to an alternative to the CCP line. To be guai, is not necessarily to be a good citizen working only for CCP interests: it is to follow one’s own path.

Serious themes aside, the film is great fun to watch. There are plenty of laugh-out-loud moments, and the abundance of fart jokes are bound to tickle the child audience. Older audiences will find the final showdown breathtaking. Some might shed a tear or two over the love between Ne Zha and his parents.

Nobody predicted Ne Zha’s phenomenal box office success. He is a good demon boy with supernatural powers who also challenges authority. Beloved by millions of fans and endorsed by the government, Ne Zha has cemented his status as China’s surprising new superhero.

Authors: Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University