farmers in Far North Queensland are being left behind by the digital economy

- Written by Amber Marshall, Research fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Farming families and communities in Queensland’s remote north are being left behind by the digital economy, putting them at significant social and economic disadvantage.

Our report, launched in Cairns today, details the impacts of low levels of “digital inclusion” among farmers in Far North Queensland (FNQ), for whom reliable internet connection is not a given.

Read more: Australia's digital divide is not going away

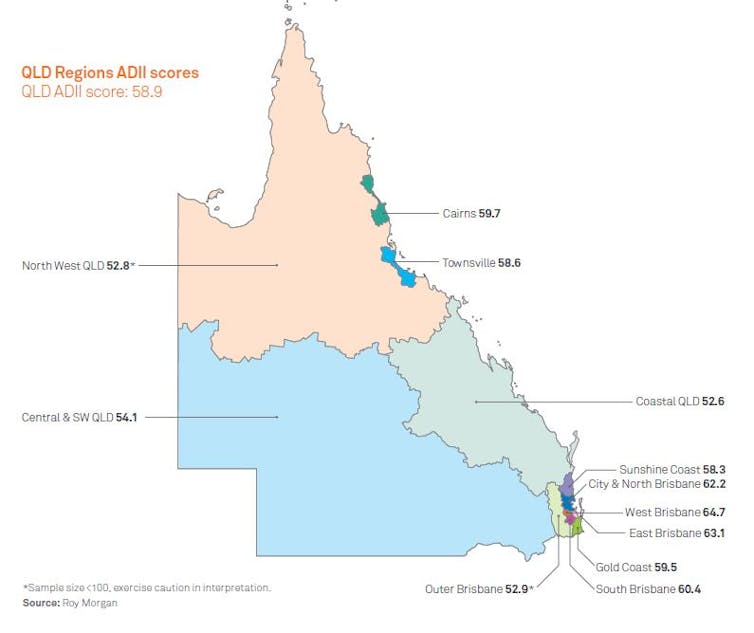

People in rural and remote areas – including Indigenous communities – score much lower than urban Australians on the Australian Digital Inclusion Index. This index – which measures access to technology, affordability of connections, and digital ability – shows that North West Queensland (which includes FNQ grazing lands) is one of the least digitally included regions in Australia.

The index also shows that farmers have lower digital inclusion scores than others in similar socioeconomic circumstances. Farmers’ experiences of digital exclusion are therefore worthy of investigation.

While some Australian farmers are getting online and adopting various forms of agricultural technology such as drones, sensors and automated vehicles, many are being left behind. Given that a 2018 federal government report on Australia’s tech future predicted that agriculture will be transformed by digital technologies, it is important to understand how best to help farmers in remote areas get on board.

Australian Digital Inclusion Index - Queensland (2018)

Australian Digital Inclusion Index - Queensland (2018)

Our research revealed a range of findings about the impacts of low levels of digital inclusion for FNQ farmers. Here are four of the main insights from the report.

Farmers pay more for less

Challenges with unreliable services, network congestion, slow internet speeds, and data caps in rural and regional Australia are well documented. In rural FNQ, mobile, internet and landline connections are often intermittent or drop out altogether. Therefore, many farmers “layer up” on service plans and devices.

For example, a FNQ farming family may have several mobile phones and plans with different providers, a satellite phone and plan, a home landline, and a wireless or satellite connection to the National Broadband Network (NBN). An urban family, meanwhile, may have just one provider that guarantees access and unlimited data to all devices in the household. Farmers pay more for less.

Data is scarce in remote households

Data scarcity is also an issue for farming families, particularly in remote households with only satellite internet connection. Unlike the unlimited fixed-line NBN plans available in urban areas, plans using NBN’s Sky Muster satellite are capped, and often more than half of the data is only available in off-peak times, such as between midnight and 7am.

Read more: Internet in space: nbn's plan to bring broadband to rural Australia

This affects how remote families live, and limits people’s access to digital opportunities. Farming women in particular have to monitor the data consumption of adults, kids, workers, and visitors – often there is not enough to go around.

Deciding what digital activities (banking, homework, job-seeking, video-calling) to prioritise – and who misses out – can be stressful and contentious.

Data scarcity is also an issue for farming families on the Savannah Way, Far North Queensland.

Amber Marshall

Data scarcity is also an issue for farming families on the Savannah Way, Far North Queensland.

Amber Marshall

Farmers need to be online to comply with the law

To meet their accreditation requirements, FNQ cattle producers must complete online modules on various topics including biosecurity, transport methods, and animal welfare. Complying with vegetation clearing laws also involves accessing maps that are only readily available online. Many farmers struggle to gain access to the internet, log in on a suitable device, navigate the online platforms, and complete the mandatory training. Many therefore risk noncompliance.

For similar reasons, some graziers are resisting digitisation of the National Livestock Identification System, which is used to track the movement of cattle nationally. This system is essential for biosecurity, meat safety, product integrity, and market access. Breaches to the system could have catastrophic consequences for the beef industry, for instance in the event of a freeze on the wider movement of cattle.

Farmers complete an online LPA animal welfare module at a Northern Gulf Resource Management Group toolbox talk, Almaden Pub.

Amber Marshall

Farmers complete an online LPA animal welfare module at a Northern Gulf Resource Management Group toolbox talk, Almaden Pub.

Amber Marshall

The network is essential

FNQ farmers rely on mobile and internet coverage across properties and between townships for all sorts of activities, from coordinating the everyday school run to responding to an emergency such as a bushfire. Although two-way radios still play an important role in emergency response, people can only respond if they are in range.

In many instances, FNQ farmers can only access reliable phone or internet from their house or the nearest township. While the national Mobile Black Spot Program is helping to bridge gaps in mobile phone service along major road routes, affordable solutions are needed to beam wifi signals substantial distances from the house.

Read more: Getting remote Indigenous communities online

What can we do to help?

There are several things government and industry could do to help improve digital inclusion in FNQ agricultural communities:

Improve mainstream telecommunications and internet infrastructure, and embrace alternative hardware solutions in communities and on properties. For example, Wi-Sky, which began as a rural cooperative, has built its own towers to offer alternative internet plans to locals in several remote sites in Queensland and New South Wales.

Redefine affordability to take account of the “layering up” phenomenon when developing telecommunications policy at all levels. Current methods to determine affordability do not accurately reflect the true cost and value for money of digital connectivity in rural areas. Telecommunications companies could revise their plans to give their rural customers better value for money, for instance by offering tailored mobile plans for intermittently heavy data users who are out of range for long periods.

Boost farmers’ digital ability to help them do business in the digital economy. Targeted digital ability programs could foster specific skills that farmers want and need, such as using the livestock identification system. These programs could be delivered in partnership with industry organisations such as AgForce that already have people on the ground in rural and remote areas.

Finally, give farmers a voice. Our policy-focused report was accompanied by two other reports focusing on participants and particular case studies. Farmers are telling us what they need to take part in the digital economy. It’s up to government and industry to listen, and to work with communities to devise solutions for improved access, affordability and digital ability.

Authors: Amber Marshall, Research fellow, Queensland University of Technology