Queenslanders are among our heaviest drinkers on nights out, and changing that culture is a challenge

- Written by Jason Ferris, Associate Professor, Program Leader for Research and Statistical Support Service and Program Leader for Substance Use and Mental Health, Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland

This is the second in a series of articles discussing a recently released comprehensive evaluation of the Queensland government’s 2016 policy reforms to tackle alcohol-fuelled violence and the implications for liquor regulation and the night-time economy in Queensland and Australia. A summary report is also available.

Our evaluation of the Queensland government’s 2016 “Tackling Alcohol-Fuelled Violence” (TAFV) policy has found Queenslanders are still drinking more heavily than people in other states when going out at night.

Despite significant reductions in serious assaults and other health-related outcomes, reported levels of aggression are also high.

Read more: Lessons from Queensland on alcohol, violence and the night-time economy

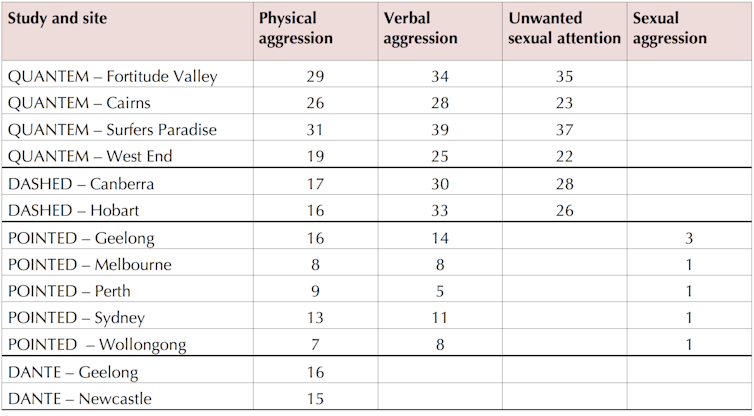

Queenslanders report much higher levels of aggression than reported in our previous studies, which asked the same question in Canberra, Hobart, Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, Wollongong, Geelong and Newcastle.

Table 1. Percentage of interviewees who report being involved in aggression in and around night-time entertainment precincts in the previous three months.

QUANTEM final report, Author provided

Table 1. Percentage of interviewees who report being involved in aggression in and around night-time entertainment precincts in the previous three months.

QUANTEM final report, Author provided

Female patrons reported experiencing more of all types of aggression than men across all precincts. The next article in this series highlights the worrying number of women who experience unwanted sexual attention while out.

To measure the impact of the 2016 policy changes on alcohol consumption, illicit drug use and aggression, our research teams conducted street intercept surveys on Saturday nights in Fortitude Valley (Brisbane), Surfers Paradise and Cairns between 2016 and 2018. All participants were breathalysed. Every fifth person was invited to participate in a saliva drug swab.

Across the precincts, 4,401 people – 57% of them male – completed surveys.

Blood alcohol concentration (BAC)

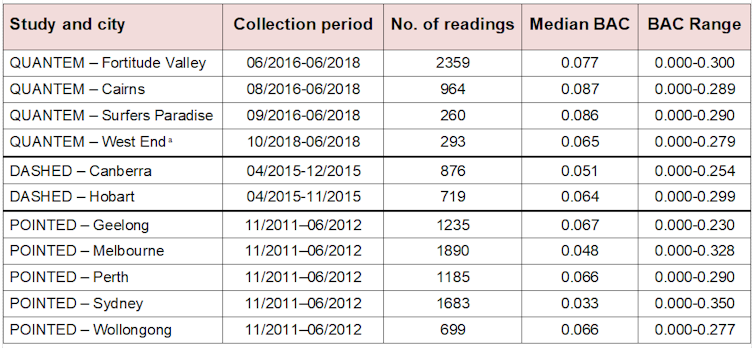

Half of patrons’ blood alcohol concentration (BAC in g/dL) readings were over 0.077 (the median value, with a range of 0.000-0.300) in Fortitude Valley, 0.086 (range 0.000-0.290) in Surfers Paradise and 0.087 (range 0.000-0.289) in Cairns. The highest reading, 0.300, is six times the legal driving limit.

These median BAC levels are much higher than other, previously studied cities. The results highlight the challenges of achieving change in Queensland’s drinking culture.

Table 2. Patrons’ median blood alcohol concentration (BAC in g/dL) and range of readings.

QUANTEM final report, Author provided

Table 2. Patrons’ median blood alcohol concentration (BAC in g/dL) and range of readings.

QUANTEM final report, Author provided

Interestingly, most patrons are more drunk than they think they are. Before undertaking a breath test patrons were asked to guess their level of intoxication. For example, in Cairns, patrons’ median guess of their BAC reading was 0.070, compared to the measured median of 0.087.

Pre-drinking

High alcohol consumption when going out to night-time entertainment precincts includes pre-drinking (drinking at home before going out; also known as pre-gaming, pre-partying or pre-loading in other countries). As our research teams have documented since 2012, pre-drinking has continued to increase.

With 84% of all patrons reporting pre-drinking before going out, Queensland shows higher levels than in most other previously studied cities.

Overall, male patrons drank significantly more than female patrons when pre-drinking. In Fortitude Valley, though, female patrons were significantly more likely to pre-drink than males.

Read more: Women's alcohol consumption catching up to men: why this matters

It’s a common belief that patrons choose to pre-drink to avoid buying more expensive drinks while they’re out in bars or clubs. But we found patrons who reported pre-drinking were more likely to drink more heavily across the night. They also reported drinking for longer than those who did not pre-drink.

Our report also shows the rate of pre-drinking across the precincts remained mostly stable in the two years after the TAFV policy was introduced in 2016. This suggests it did not affect rates of pre-drinking.

Illicit drug use

Rates of self-reported illicit drug use varied between precincts, from 13% of patrons in Fortitude Valley to 25% of all patrons in Surfers Paradise.

Ecstasy was the most commonly used illicit substance reported by patrons (5.5%), followed by cannabis (4%).

Among those who completed saliva drug swabs, the most commonly detected substances were amphetamines in Fortitude Valley and Cairns. In Surfers Paradise, however, it was methamphetamine; with 23.5% of patrons interviewed in Surfers Paradise testing positive for the substance.

Although rates of illicit drug use fluctuated in the two years after the TAFV policy was introduced, overall rates remained largely stable. This indicates the policy did not result in a clear increase or decrease in illicit drug use.

Read more: Fact check: only drugs and alcohol together cause violence

So what does it all mean?

Historically, Queensland has high levels of harmful consumption of alcohol, especially in high-risk groups. Around 46% of Queenslanders have exceeded single-occasion risk guidelines in the past year, higher than in New South Wales and Victoria.

There has been significant investment in education campaigns across social media and in schools. Despite this, Queenslanders continue to show hazardous levels of alcohol consumption, illicit drug use and experiences of aggression.

Changing cultural patterns relating to pre-drinking and alcohol-related harms will not be easy. Previous research suggests further tightening of licensed venues’ trading hours will help. Our report recommendations include introducing a minimum unit price on alcohol and promoting low-risk drinking guidelines at all points of sale across Queensland.

Our report also recommends trialling live music early in the night to try to bring people into entertainment districts earlier.

Despite the promising results of government policy efforts to date, our evaluation suggests the work to reduce alcohol-related harm across Queensland is not finished.

Read more: FactCheck: can you change a violent drinking culture by changing how people drink?

Authors: Jason Ferris, Associate Professor, Program Leader for Research and Statistical Support Service and Program Leader for Substance Use and Mental Health, Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland