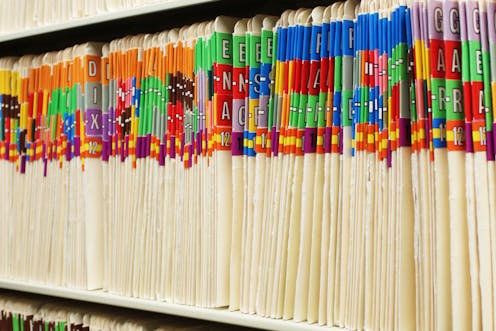

how the move to digital medical records is leaving us drowning in old paper files

- Written by Gillian Oliver, Associate Professor and Director, Centre for Organisational & Social Informatics, Monash University

The recent case of paper medical files from a Brisbane hospital found on a busy street highlights the need for secure, controlled disposal of medical records.

The files were said to be from out-patient clinics and contained patient names and their appointments, but not medical details. Now Queensland Health is investigating the circumstances of how the files came to be found in public, rather than being safely destroyed by a contractor.

So how are hospitals and clinics handling their old paper records as they move to electronic systems? How are they dealing with the tsunami of files that need to be safely disposed of?

Read more: The Cabinet Files show that we need to change the nature of record-keeping

Your medical records, whether paper or electronic, need to be kept while they’re relevant to your care, with restricted access to protect your privacy. But who decides when medical records are no longer needed? What happens then?

Governments at all levels have legislation for this. For instance, the Queensland health department specifies what is destroyed and when, according to a schedule from Queensland State Archives. This covers medical records in the public health care system in physical form (paper, photographs, film), in electronic form or a mixture of the two.

This, for example, says “records displaying evidence of clinical care to an individual or groups of adult patients/clients” should be kept “for ten years after last patient/client service provision or medico-legal action”. There are a number of exceptions relating to, for example, clinical trials, mental health and communicable diseases. For each exception, there is a specific time period of how long the file needs to be kept.

Queensland State Archives also advises on how records are to be securely destroyed, either by shredding, pulping or burning.

Read more: Our healthcare records outlive us – it's time to decide what happens to the data once we're gone

Hospitals can contract commercial services to destroy paper files. But the document owner, in this case the hospital, is ultimately responsible for ensuring this is carried out legally.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has established practice standards for GP clinics. These require the secure destruction (for instance, by shredding) of paper records before disposal.

So, hospitals and GP clinics need to develop and implement policies and procedures that state explicitly when and how medical records should be disposed of, and also keep a record of when that happens.

However, to determine whether an individual medical record among the vast quantities held has passed its “use by date” can be extremely resource-intensive for administrative staff.

This means the ultimate driver of paper record destruction is more likely to be the need to free up expensive office or storage space. It’s this sort of scenario that might eventually play out into records being accidentally or deliberately dumped wherever, whenever.

The move towards digital records

The Brisbane situation highlights the limitations of “business as usual” in relation to medical records, which includes paper records held in multiple locations, in hospitals, in GP clinics and with specialists.

Consider your own medical record “paper trail”, which may include files from hospital admissions, records held by your local doctor or other specialist, and results of blood tests and x-rays performed elsewhere.

At both a personal and whole-of-population level, there are clearly numerous opportunities for unintended access to these physical documents. Centrally and securely stored electronic records can address this risk, and also carry a number of other advantages.

Read more: Opting out of My Health Records? Here's what you get with the status quo

Privacy breaches relating to paper medical records are in part a function of a worldwide transition from a trusted familiar environment of paper records to electronic medical records.

This dramatically multiplies the volume of paper records needing to be destroyed — from only those that are “out of date” to every record that is scanned and made redundant.

The Brisbane case also highlights the sensitivity of medical records in all their forms, a factor also playing out in the My Health Record debate.

Read more: My Health Record: the case for opting out

Who do we trust to keep our sensitive medical records safe? Should our trust be placed in the old paper records (part of the the status quo) or a centralised electronic medical record?

The Brisbane situation, by highlighting the limitations of paper records, certainly challenges notions of trusting the familiar and favouring the status quo.

Read more: My Health Record: the case for opting in

So, what can we expect?

Like all transitions of this scale, there are a range of costs involved in moving from paper to electronic medical records, one of which is the prospect of further paper record data breaches as mountains of redundant records are destroyed. However these transition costs need to be balanced against the ultimate benefit of electronic records.

Even accepting these benefits doesn’t necessarily mean people will automatically become more comfortable with electronic medical records, like My Health Record. For that to occur, people also have to overcome a general lack of trust in government.

However, our research shows it is possible to encourage people to use online government services. By harnessing behavioural science, we have shown that providing customer support and promoting the benefits and ease of online services helps the transition from queuing and paper forms to using online services.

Hope for the future

In the rush to drag people to shiny new online platforms, this illustrates the simple act of talking people through the advantages and supporting their transition can address many of the psychological barriers to change.

Then, hopefully, we can see the end of paper medical records and services, and fewer paper records being dumped on the side of the road. As long as paper records exist they will be vulnerable to unauthorised access – either within a storage facility or in transit to destruction. However, each case of unauthorised access is dwarfed by the number of paper records successfully and securely destroyed, never able to be physically accessed again.

Authors: Gillian Oliver, Associate Professor and Director, Centre for Organisational & Social Informatics, Monash University