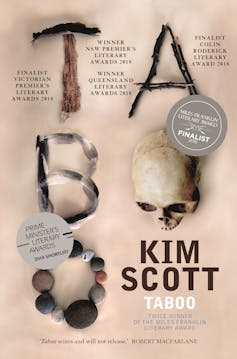

the all-knowing narrator in Kim Scott's Taboo

- Written by Julienne van Loon, Vice Chancellor's Principal Research Fellow, School of Media & Communication, RMIT University

Why do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In this series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

The omniscient narrator – an all-knowing, third-person voice – is making a return to contemporary fiction. Indigenous Australian author Kim Scott, in choosing this technique for his latest award-winning novel, Taboo, is not alone: we can also find it in recent fiction by Zadie Smith (White Teeth; On Beauty) and Richard Powers (The Overstory).

Readers might be surprised by this trend. Isn’t the penchant to narrate in this way – like a kind of god – long dead? Curiously, the answer is no.

Along with several of his peers, Kim Scott is playing with a mode of omniscience deeply informed by the legacy of postmodernism in literature, a movement characterised by, among other things, a critique of the unreliable narrator. As with all of Kim Scott’s fiction, it matters deeply who it is that is speaking.

Literary scholar Paul Dawson has argued that the reappearance of the omniscient narrator in recent fiction can be read as “a performance of narrative authority”. He suggests one reason omniscience has returned is the anxiety many writers now feel about the role and place of storytelling in contemporary culture, where freely available digital media stories, peppered with fake news, produce and reproduce endlessly. As a result, there is very little about in the way of the consistently reliable narrative authority.

Pan Macmillan

Enter Kim Scott’s omniscient narration in Taboo. Here is a narration that is playfully performative, in part to acknowledge and perhaps counter the many problems with narrative authority in contemporary life, but also to approach a very difficult topic.

This is a novel about a massacre site, and the question of how to adequately acknowledge what such a site means for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in the present.

Questions around power and narration are entirely pertinent in this context. Whose history is this? And who can tell it adequately? Who has the authority? Who, even, has an adequate handle on the story?

The sense of the flesh-and-blood Indigenous Australian author, Kim Scott, is ever present behind the text. Curiously, he even inserts an Afterword, a non-fiction commentary on his intentions with the novel, directly following the final page. It is an exegesis, or explanation, of sorts. But in and through the novel itself, the omniscient voice is not the implied voice of the author. It is something else entirely.

Read more:

From Benang to Taboo, Kim Scott memorialises events we don't want to remember

Reviewing Taboo for the Sydney Morning Herald, literary critic Peter Pierce describes the novel as having an “oracular” voice. Pierce may simply mean that the voice of the novel is enigmatic, but Scott’s narration is also oracular in the sense of employing a voice that claims the authority of an oracle – a source of wisdom from some higher, more ancient order of meaning.

Sometimes this makes the book feel like a work of magic realism, where the magical creeps into the real world, as in the opening pages:

We thought to tell a story with such momentum; a truck careering down a hillside, thunder in a rocky riverbed, a skeleton tumbling to the ground. There must be at least one brave and resilient character at its centre (one of us), and the story will speak of magic in an empirical age; of how our dead will return, transformed, to support us again and from within.

Reviewer Jane Gleeson-White has described the voice of the book as belonging to “‘undead’ Noongar ancestors who rise from the riverbed to narrate”. This is functionally correct, but Scott’s text is not a conventional ghost story, nor is the first-person plural, with its sense of a haunting presence, heavily laboured.

Pan Macmillan

Enter Kim Scott’s omniscient narration in Taboo. Here is a narration that is playfully performative, in part to acknowledge and perhaps counter the many problems with narrative authority in contemporary life, but also to approach a very difficult topic.

This is a novel about a massacre site, and the question of how to adequately acknowledge what such a site means for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in the present.

Questions around power and narration are entirely pertinent in this context. Whose history is this? And who can tell it adequately? Who has the authority? Who, even, has an adequate handle on the story?

The sense of the flesh-and-blood Indigenous Australian author, Kim Scott, is ever present behind the text. Curiously, he even inserts an Afterword, a non-fiction commentary on his intentions with the novel, directly following the final page. It is an exegesis, or explanation, of sorts. But in and through the novel itself, the omniscient voice is not the implied voice of the author. It is something else entirely.

Read more:

From Benang to Taboo, Kim Scott memorialises events we don't want to remember

Reviewing Taboo for the Sydney Morning Herald, literary critic Peter Pierce describes the novel as having an “oracular” voice. Pierce may simply mean that the voice of the novel is enigmatic, but Scott’s narration is also oracular in the sense of employing a voice that claims the authority of an oracle – a source of wisdom from some higher, more ancient order of meaning.

Sometimes this makes the book feel like a work of magic realism, where the magical creeps into the real world, as in the opening pages:

We thought to tell a story with such momentum; a truck careering down a hillside, thunder in a rocky riverbed, a skeleton tumbling to the ground. There must be at least one brave and resilient character at its centre (one of us), and the story will speak of magic in an empirical age; of how our dead will return, transformed, to support us again and from within.

Reviewer Jane Gleeson-White has described the voice of the book as belonging to “‘undead’ Noongar ancestors who rise from the riverbed to narrate”. This is functionally correct, but Scott’s text is not a conventional ghost story, nor is the first-person plural, with its sense of a haunting presence, heavily laboured.

Author Kim Scott employs an omniscient voice in his latest novel.

Pan Macmillan

Read more:

Explainer: magical realism

For much of the novel, we are focused upon the key protagonist, Tilly, in a way that could easily be mistaken for conventional realism. Except that it isn’t. Scott regularly disrupts that notion through shifts of perspective, a regular pulling back to the bigger picture. Here is one example, where the reader’s “sitting” on Tilly’s shoulder as she looks out the window of her group’s tour bus is interrupted by another viewpoint, one she cannot be simultaneously aware of:

Seen through the insect-smeared windscreen: scarcely undulating, dry and bleached ground; fence lines beside the road and dividing, at wide intervals, a mostly bare landscape. A fence is just the posts holding hands, thought Tilly, and such long arms in between them … “This place, Tilly, where we’re going” Gerry began, but Tilly was not listening and he let the words die. No one took up the conversation.

Taboo’s omniscient narration is gently provocative. It prods us to think about being or existence, for the novel’s unseen collective voice is more-than-human. As an ancestral voice, it is possible to understand our narrator(s) as a life expanded beyond the human form to encompass land, water, fire and curlew. We are encouraged to shift our thinking beyond the human-centric and towards the relation between human and other forms, especially ecological ones.

Consider, for example, this passage from the end of the novel, when an elderly Tilly is pictured at some point in the future, contemplating a pile of tree branches in a forest:

[She] would see not timber limbs but the bones of something new and ancient, something recreated and invigorated, and would think of when she first heard a voice rumbling from a riverbed, and how something reached out to her.

Did Scott just suggest that a riverbed might have a voice? That an energy without form might have reach?

To some extent, the meaning we take from Taboo depends upon how we think about the whole notion of omniscience. In my view, Scott’s choice of narrative technique works to ask of us as humans an increasingly important question: where are our limits? His use of omniscient narration might therefore be understood as a not just a literary choice, but a philosophical and ethical one.

Author Kim Scott employs an omniscient voice in his latest novel.

Pan Macmillan

Read more:

Explainer: magical realism

For much of the novel, we are focused upon the key protagonist, Tilly, in a way that could easily be mistaken for conventional realism. Except that it isn’t. Scott regularly disrupts that notion through shifts of perspective, a regular pulling back to the bigger picture. Here is one example, where the reader’s “sitting” on Tilly’s shoulder as she looks out the window of her group’s tour bus is interrupted by another viewpoint, one she cannot be simultaneously aware of:

Seen through the insect-smeared windscreen: scarcely undulating, dry and bleached ground; fence lines beside the road and dividing, at wide intervals, a mostly bare landscape. A fence is just the posts holding hands, thought Tilly, and such long arms in between them … “This place, Tilly, where we’re going” Gerry began, but Tilly was not listening and he let the words die. No one took up the conversation.

Taboo’s omniscient narration is gently provocative. It prods us to think about being or existence, for the novel’s unseen collective voice is more-than-human. As an ancestral voice, it is possible to understand our narrator(s) as a life expanded beyond the human form to encompass land, water, fire and curlew. We are encouraged to shift our thinking beyond the human-centric and towards the relation between human and other forms, especially ecological ones.

Consider, for example, this passage from the end of the novel, when an elderly Tilly is pictured at some point in the future, contemplating a pile of tree branches in a forest:

[She] would see not timber limbs but the bones of something new and ancient, something recreated and invigorated, and would think of when she first heard a voice rumbling from a riverbed, and how something reached out to her.

Did Scott just suggest that a riverbed might have a voice? That an energy without form might have reach?

To some extent, the meaning we take from Taboo depends upon how we think about the whole notion of omniscience. In my view, Scott’s choice of narrative technique works to ask of us as humans an increasingly important question: where are our limits? His use of omniscient narration might therefore be understood as a not just a literary choice, but a philosophical and ethical one.

Authors: Julienne van Loon, Vice Chancellor's Principal Research Fellow, School of Media & Communication, RMIT University

Read more http://theconversation.com/inside-the-story-the-all-knowing-narrator-in-kim-scotts-taboo-117587