A disc of dust and gas found around a newborn planet could be the birthplace of moons

- Written by Valentin Christiaens, Research Fellow in Astrophysics, Monash University

When Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei first spotted four moons of Jupiter through a telescope, he realised that not everything goes around the Earth, as was the prevailing theory in 1610.

The presumed origin of the Galilean moons was in a swirling circumplanetary disc of gas and dust around the newborn Jupiter.

Jupiter and the four Galilean moons, a composite of several images as seen through a telescope.

Flickr/Thomas Bresson, CC BY

Jupiter and the four Galilean moons, a composite of several images as seen through a telescope.

Flickr/Thomas Bresson, CC BY

But evidence of a circumplanetary disc eluded astronomers, despite an intensive search. Until now.

Read more: How we found a white dwarf – a stellar corpse – by accident

We detected the first evidence for one of these discs in the form of an infrared glow around a baby planet called PDS 70 b, the details published in two papers this week.

It was not easy to find

The discovery required one of the largest telescopes on Earth (the creatively named Very Large Telescope in Chile), a sophisticated spectrograph (SINFONI) to acquire images at different wavelengths in the infrared, and new image-processing algorithms developed specifically for the dataset we gathered.

The newborn planet orbits a star called PDS 70, which is young and relatively close to us (a trifling 369 light years away) in what is known as the Upper Centaurus-Lupus star-forming region of the Milky Way.

The star is just a baby itself, less than 10 million years old. In stellar terms PDS 70 is barely out of nappies (our Sun is 4.6 billion years old).

Apart from its youth and proximity, the main reason we chose to study PDS 70 is that previous observations showed a large hole or gap in the disc of gas and dust surrounding the star.

This hole, covering an area almost the size of our Solar System, hints at the presence of planets orbiting the star, which are responsible for carving away the disc material.

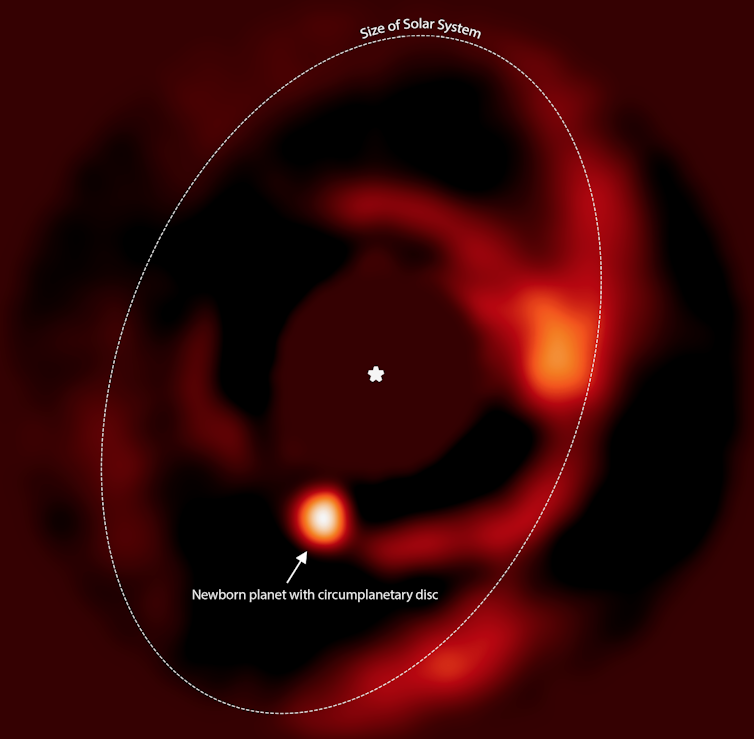

Infrared image of the newborn planet PDS 70 b (the bright spot, bottom left) and its circumplanetary disc. The actual star is in the centre of the image (marked by *) but its glare blocked out by the processing. The second brightest spot (above right) is thought to be another planet forming and is being studied by other researchers.

Valentin Christiaens et al./ESO, Author provided

Infrared image of the newborn planet PDS 70 b (the bright spot, bottom left) and its circumplanetary disc. The actual star is in the centre of the image (marked by *) but its glare blocked out by the processing. The second brightest spot (above right) is thought to be another planet forming and is being studied by other researchers.

Valentin Christiaens et al./ESO, Author provided

The new images we gathered show that the gap is not entirely empty. They reveal an arc of gas, spirals and a bright blob, which had first been detected and interpreted as a baby planet in two studies published last year.

And it’s a whopper planet - about 10 times heavier than Jupiter.

In the infrared

What is new in our analysis is that we probed red light from the planet in more detail than previous studies. We were able to show for the first time that the planet’s infrared colours cannot be explained by its atmosphere alone.

Instead, this excess infrared excess suggests the presence of a circumplanetary disc, just like the one imagined as the birthplace of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons – Io, Europe, Ganymede and Callisto.

Decades ago, the same argument was used as evidence for the presence of protoplanetary discs, the dusty discs of gas around baby stars that are the birthplaces of planets themselves.

An illustration of a protoplanetary disk: the rings around young star suggest planet formation in progress.

Shutterstock/Jurik Peter

An illustration of a protoplanetary disk: the rings around young star suggest planet formation in progress.

Shutterstock/Jurik Peter

Now we can use the same techniques but on a smaller scale to see the birthplace of moons.

The tricky part is that spotting planets with a telescope is like staring into car headlights and trying to spot a firefly. We first had to model and subtract the bright glare of the star, to spot the feeble glow of the planet.

In our processed image (above) we carefully deleted the starlight (we show the location with an asterisk), revealing both the planet and faint structures in the disc surrounding the star.

Possible moons

The discovery of the four largest moons of Jupiter four centuries ago gave astronomers a first hint that giant planets must form surrounded by a circumplanetary disc.

Plenty of work has been done since to try to understand their properties, but we finally have direct confirmation that they exist. It’s the culmination of a long search.

Read more: Observing the invisible: the long journey to the first image of a black hole

It’s also exciting. Our work shows that theoretical models of giant planet formation were not too far off. There is now the possibility that moons could be forming right now in the circumplanetary disc around PDS 70 b.

It’s hoped the new algorithm we developed can now be used to attempt to extract faint signals from other complex datasets of planets forming in other star systems.

It blows the mind to think we might see other planets and even moons in the process of formation, using the biggest telescope in the world. It’s just another reminder of how small and insignificant we really are.

Authors: Valentin Christiaens, Research Fellow in Astrophysics, Monash University