can your employer sack you for what you say or do in your own time?

- Written by Anthony Forsyth, Professor of Workplace Law, RMIT University

It probably wasn’t exactly how egg-tossing activist Amber Holt thought her hit on prime minister Scott Morrision would go down. The egg bounced off his head. He cracked jokes about it. She’s been charged with common assault, and may yet lose her job for her efforts.

“I’ve got to go to work, no comment,” she told media after the incident, with a Cotton On Kids lanyard visible around her neck. The clothing company has since confirmed Holt is a casual employee and that it is “investigating” the incident.

“The Cotton On Group is disappointed to hear about yesterday’s incident involving one of our team members,” it said in a statement. “While individuals are entitled to hold their own opinions, we do not condone this behaviour and it does not align with our company values.”

Does Cotton On, or any other employer, have the right to sack an employee for something they say or do in their own time?

The short answer is, in many cases, yes – especially if the business can show the employee’s actions reflect badly on it. In this case the company might find Holt has breached her obligations as an employee to protect the company’s image.

Amber Holt, with Cotton On Kids lanyard, after attempting to egg Scott Morrison on Tuesday, May 7, 2019.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Amber Holt, with Cotton On Kids lanyard, after attempting to egg Scott Morrison on Tuesday, May 7, 2019.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Employment law

Australian employment law requires that an employee cooperate with their employer, and not engage in any conduct that would undermine the business or bring it into disrepute.

These are terms implied into every employee’s contract of employment by the common law. Over the past 30 years or so, the courts have increasingly interpreted these principles to enable employers to control the private or out-of-hours conduct of employees.

You could therefore find yourself lawfully sacked for untoward behaviour at a work Christmas party, or for posting derogatory comments about the business on Facebook – so long as your employer can show there is a sufficient connection to the employment.

That connection will exist where, for example, drunken behaviour at a party affects your workplace relationships (or constitutes sexual harassment), or where your “private” Facebook post damages the employer’s reputation.

This is why Fair Work Australia upheld a Good Guys franchise dismissing an employee because of his Facebook comments about colleagues, including one interpreted as a threat.

On the other hand Fair Work ruled lighting company LED Technologies had unfairly dismissed an employee for “rude and vulgar” Facebook comments, which he argued was about his mother’s workplace, not his own.

Codes of conduct

Employers have also sought to extend the common law obligations of employees through company policies and codes of conduct. Typically these documents impose very high standards of employee behaviour in a wide range of situations. The employer is then able to discipline or dismiss you for behavioural breaches, even outside the workplace or work hours, especially where (as is common) you have signed a contract in which you agree to observe company policies.

In the past five years we have seen many examples of the collision between “corporate values” and employees’ right to a “private life”.

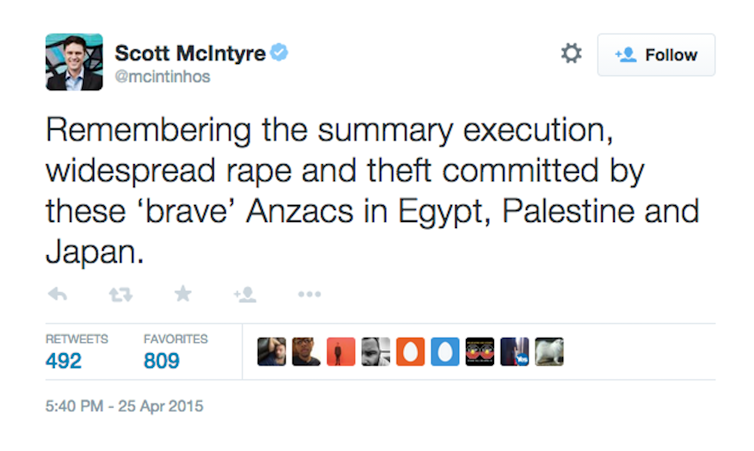

In 2015, SBS dismissed sports journalist Scott McIntyre for tweeting on Anzac Day a series of comments critical of Australia’s obsession with the Anzac legend. McIntyre’s Twitter account identified him as an SBS employee, and he had more than 30,000 followers. SBS sacked him the next day on the grounds his “disrespectful” comments breached the public broadcaster’s code of conduct and social media policy.

One of Scott McIntyre’s offending tweets.

One of Scott McIntyre’s offending tweets.

McIntyre contested his dismissal in the Fair Work Commission. He argued he had a legal right to express a political opinion and had been discriminated against for exercising that right. The parties reached a settlement out of court, so we didn’t get a ruling on a few important issues. Did the tweets amount to “political opinion”? If they did, would anti-discrimination laws have trumped employer policies?

Read more: Anzacs behaving badly: Scott McIntyre and contested history

Last month, the Federal Circuit Court ruled James Cook University had unlawfully dismissed a physics professor, Peter Ridd, for making public comments critical of university colleagues for their research on the effects of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef.

This case was a bit different, though. The university argued Ridd breached its code of conduct. But the court decided Ridd had a right to intellectual freedom under the university’s enterprise agreement (a common feature of academic employment).

Later this year the High Court will consider an appeal by Comcare, the federal workers’ compensation agency, against an Administrative Appeals Tribunal ruling that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection unfairly dismissed public servant Michaela Banerji in 2013 for (anonymously) tweeting comments critical of the federal government’s immigration policy.

The tribunal determined Banerji’s right to make such comments was protected by the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. Her dismissal therefore constituted unlawful administrative action. The tribunal likened seeking to control the anonymous political comments of a departmental employee to the Orwellian notion of “thoughtcrime” in 1984.

Read more: Is liking something on Facebook 'protected political speech'? It depends

In 2017 the Australian Public Service Commission was widely criticised for issuing a new social media policy seen to intrude excessively on the right of government employees to engage in free speech.

And of course we’re now witnessing the Israel Folau case. A Rugby Australia panel this week decided he breached the players’ contract through his social media posts critical of homosexuality. It is yet to decide on a penalty but if he’s sacked, I can definitely see this one being challenged, Folau arguing discrimination on the basis of his religion.

Employer’s prerogative

Cotton On’s employee code of conduct is not publicly available – possibly because of the adverse publicity it received in 2015, when it was revealed its code required employees to “keep it real” and observe other company values like being “fun”, “ethical” and “entrepreneurial”.

However, I expect the code of conduct would include language broad enough for Cotton On to argue Holt has engaged in misconduct that has damaged its public reputation. An important factor here is that she is charged with high-profile criminal behaviour. She might try to argue she was expressing political views, protected by discrimination law, but this doesn’t look like the right “test case” to win that argument.

Only where there are clear protections of employee free speech (such as for academics) is the steady march of employer policies controlling employees’ private conduct likely to be halted. Unfortunately most of the Australian workforce is not covered by these protections.

Authors: Anthony Forsyth, Professor of Workplace Law, RMIT University