Guinea flowers are fierce and golden

- Written by Betsy Jackes, Adjunct professor, James Cook University

Welcome to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian. Read more about the series here or get in touch to pitch a plant at batb@theconversation.edu.au.

I first became interested in guinea flowers when I heard of a plant growing in Queensland’s White Mountains nicknamed “excruciating” by all who handled it, because of the pungent needle-like leaves which attached themselves to fingers and clothes.

This species is a guinea flower, now scientifically named Hibbertia ferox, meaning “fierce”. Guinea flowers grow across Australia, from the rainforest to semi-arid areas.

Read more: Sandpaper figs make food, fire, medicine and a cosy home for wasps

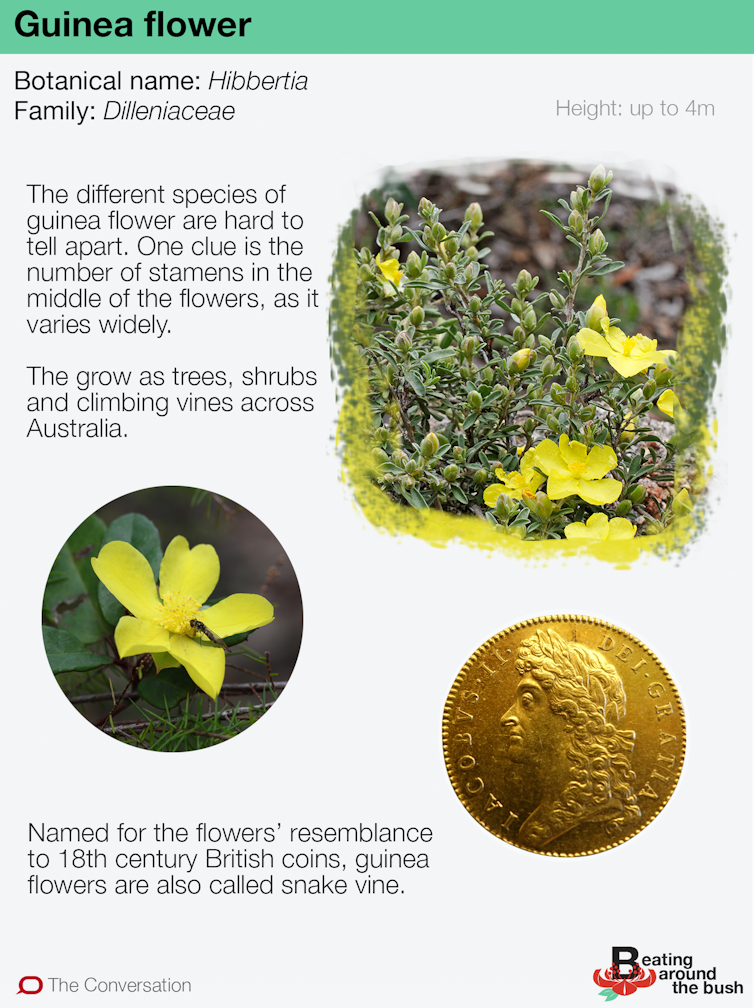

Guinea flowers belong to the genus Hibbertia, which dates back to Gondwana. Members of the genus are easy to recognise, but individual species are hard to tell apart. Their brilliant yellow (or sometimes orange) flowers have petals with a notch at the apex, and they were thought to resemble the appearance of the 18th-century coin known as a golden guinea. As usual there are a couple of exceptions – at least two species have petals that lack a notch.

All too often these small shrubs and woody climbers grow in areas likely to be razed for urban sprawl or mining.

The Conversation

What we know about Hibbertia

English merchant and amateur botanist Henry Charles Andrews named the genus Hibbertia after his friend George Hibbert (1757-1837). Andrews was an artist and engraver as well as a botanist, and the first species he named was based on a plant collected around Port Jackson.

Around 200 species are recognised but there are many unnamed varieties, particularly in tropical areas. Probably the most widespread species and one of the few cultivated is the climbing guinea flower (Hibbertia scandens). It can be grown readily from cuttings but germinates slowly from seeds.

Most species have hairs covering the leaves, which can be critical for identifying a species. Under a good hand lens or a simple microscope their variety and beauty is obvious. In some species the hairs are straight. In others they are branched with arms resembling the spokes on a star, the so-called “stellate hairs”.

Some species have scales – flat, plate-like structures – on their leaves and flowers. Sometimes there are large and small scales on the one surface.

The leaves are also diverse in shape and form: some leaves are shaped like spear and thick, as in Hibbertia banksii of the eastern Cape York area, others are needle-like with margins rolled towards the lower midrib, with a sharp, blood-drawing tip, as in Hibbertia ferox.

The Conversation

What we know about Hibbertia

English merchant and amateur botanist Henry Charles Andrews named the genus Hibbertia after his friend George Hibbert (1757-1837). Andrews was an artist and engraver as well as a botanist, and the first species he named was based on a plant collected around Port Jackson.

Around 200 species are recognised but there are many unnamed varieties, particularly in tropical areas. Probably the most widespread species and one of the few cultivated is the climbing guinea flower (Hibbertia scandens). It can be grown readily from cuttings but germinates slowly from seeds.

Most species have hairs covering the leaves, which can be critical for identifying a species. Under a good hand lens or a simple microscope their variety and beauty is obvious. In some species the hairs are straight. In others they are branched with arms resembling the spokes on a star, the so-called “stellate hairs”.

Some species have scales – flat, plate-like structures – on their leaves and flowers. Sometimes there are large and small scales on the one surface.

The leaves are also diverse in shape and form: some leaves are shaped like spear and thick, as in Hibbertia banksii of the eastern Cape York area, others are needle-like with margins rolled towards the lower midrib, with a sharp, blood-drawing tip, as in Hibbertia ferox.

A 1795 guinea coin from the reign of George III.

Wikipedia

The flowers are usually solitary and roughly 2cm in diameter, but in some of the northern species they grow in spikes roughly 4-5cm across.

Five sepals surround the five petals, which are broadest towards the top. The flowers usually close at night and reopen the next day.

A distinctive feature is the arrangement of the stamens (the male parts). These may be all on one side of the carpels (the structures containing the unfertilised seeds at the centre of the flower) or may form a form a ball in the centre. The number varies between species from fewer than 10 to more than 100.

A 1795 guinea coin from the reign of George III.

Wikipedia

The flowers are usually solitary and roughly 2cm in diameter, but in some of the northern species they grow in spikes roughly 4-5cm across.

Five sepals surround the five petals, which are broadest towards the top. The flowers usually close at night and reopen the next day.

A distinctive feature is the arrangement of the stamens (the male parts). These may be all on one side of the carpels (the structures containing the unfertilised seeds at the centre of the flower) or may form a form a ball in the centre. The number varies between species from fewer than 10 to more than 100.

Hibbertia ferox was nicknamed ‘excruciating’ because of its needle-like leaves.

Shutterstock

Floral frolics

For a plant to be involved in sex of a floral kind it needs to offer rewards for services rendered. Sometimes guinea flowers grow sterile stems, which add to the floral display and provide a food source, particularly for beetles. They are messy eaters, chewing on various plant tissues as they wander around the flower’s surface, but they do help to transfer pollen to the stigmas, or female parts (and no doubt are involved in sex with their own kind).

Guinea flowers don’t produce nectar to tempt pollinators, but people have reported them producing weak fragrance. There’s some dispute over how pleasant the smell is, with some describing it as sweet and others insisting it smells like cow dung. There have been only a couple of reports of what this smell resembles, so we need you to go and stick your nose in a freshly open flower. (Make sure to check – is the fragrance there all day or only in the morning?)

However, there is plenty of pollen. If you look closely at the anthers, those yellow sacs on the top of a thin stalk, you will see either an opening or pore at the top, or a slit down the side through which pollen can escape. Whether the marauding bug causes the pollen to spray out through the top or it accidentally falls on the bug through the slit, the bug gets dusted in pollen and then this can get brushed off on the female parts or stigma. Bees and flies are the most common bugs seen around guinea flowers.

The fruit is composed of 2-5 loosely adhering capsule-like follicles, surrounded by the five sepals, which remain and do not fall off.

Hibbertia ferox was nicknamed ‘excruciating’ because of its needle-like leaves.

Shutterstock

Floral frolics

For a plant to be involved in sex of a floral kind it needs to offer rewards for services rendered. Sometimes guinea flowers grow sterile stems, which add to the floral display and provide a food source, particularly for beetles. They are messy eaters, chewing on various plant tissues as they wander around the flower’s surface, but they do help to transfer pollen to the stigmas, or female parts (and no doubt are involved in sex with their own kind).

Guinea flowers don’t produce nectar to tempt pollinators, but people have reported them producing weak fragrance. There’s some dispute over how pleasant the smell is, with some describing it as sweet and others insisting it smells like cow dung. There have been only a couple of reports of what this smell resembles, so we need you to go and stick your nose in a freshly open flower. (Make sure to check – is the fragrance there all day or only in the morning?)

However, there is plenty of pollen. If you look closely at the anthers, those yellow sacs on the top of a thin stalk, you will see either an opening or pore at the top, or a slit down the side through which pollen can escape. Whether the marauding bug causes the pollen to spray out through the top or it accidentally falls on the bug through the slit, the bug gets dusted in pollen and then this can get brushed off on the female parts or stigma. Bees and flies are the most common bugs seen around guinea flowers.

The fruit is composed of 2-5 loosely adhering capsule-like follicles, surrounded by the five sepals, which remain and do not fall off.

Hibbertia scandens, a climbing guinea flower, is commonly known as snake vine.

Shutterstock

The fruit contains one or two seeds that are covered by a reddish coating or aril. This nutritious tissue is a valuable food source for dispersers such as ants and birds; birds have been recording spreading the seeds of Hibbertia scandens. However, in the drier areas where these plants are commonly found, ants appear to be the common dispersers.

So next time you are in the bush don’t just ignore that small shrubby plant with yellow flowers and notched petals. Stop and admire their beauty.

Read more:

Sustainable shopping: your guilt-free guide to flowers this Valentine's Day

Note if there are any bugs visiting and what they might be doing. Why not record their presence on iNaturalist – an app that lets us record and share your nature encounters – particularly if you are off the beaten track?

Hibbertia scandens, a climbing guinea flower, is commonly known as snake vine.

Shutterstock

The fruit contains one or two seeds that are covered by a reddish coating or aril. This nutritious tissue is a valuable food source for dispersers such as ants and birds; birds have been recording spreading the seeds of Hibbertia scandens. However, in the drier areas where these plants are commonly found, ants appear to be the common dispersers.

So next time you are in the bush don’t just ignore that small shrubby plant with yellow flowers and notched petals. Stop and admire their beauty.

Read more:

Sustainable shopping: your guilt-free guide to flowers this Valentine's Day

Note if there are any bugs visiting and what they might be doing. Why not record their presence on iNaturalist – an app that lets us record and share your nature encounters – particularly if you are off the beaten track?

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.. Read previous instalments here.

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.. Read previous instalments here.

Authors: Betsy Jackes, Adjunct professor, James Cook University

Read more http://theconversation.com/guinea-flowers-are-fierce-and-golden-109189