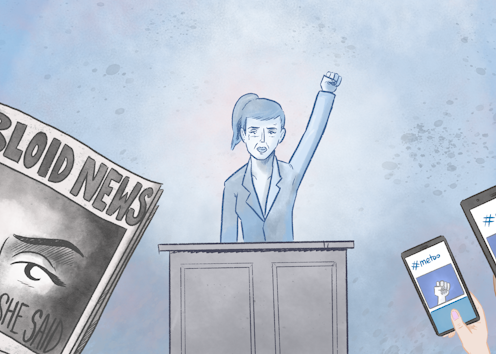

#MeToo has changed the media landscape, but in Australia there is still much to be done

- Written by Bianca Fileborn, Lecturer in Criminology, University of Melbourne

Emerging in October 2017 in response to allegations of sexual assault perpetrated by Hollywood movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo highlighted the potential for traditional and social media to work together to generate global interest in gender-based violence. Within 24 hours, survivors around the world had used the hashtag 12 million times.

Eighteen months later, #MeToo is showing few signs of slowing down. Stories continue to appear in world media about sexual harassment and assault. The accused are predominantly powerful men in the entertainment industry, with musician Ryan Adams providing a recent example.

Read more: What the Harvey Weinstein case tells us about sexual assault disclosure

More recently, we have seen the corporate world tapping into the potential of #MeToo to ask how men can do better to call out sexist attitudes and behaviours that condone violence against women. The one that caused the most debate was Gillette’s advertisement questioning whether this is the “best a man can be?”

The #MeToo movement has undoubtedly reverberated through our cultural and political landscape. It is hard to deny its impact.

What is less clear is whether it is changing how we discuss gender-based violence and gender equality, and whose experiences are able to be shared. This is especially so given the well-documented issues with media reporting on gender-based violence.

Mainstream media reporting on sexual violence

While sexual violence has received increased media attention in the wake of #MeToo, it is also important to interrogate how it is being talked about. Arguably, much of the #MeToo reporting reproduces problematic stereotypes and reinforces sexual violence as monstrous and removed from everyday life.

One analysis of journalists’ reporting on Harvey Weinstein in our forthcoming book on the #MeToo movement found that the media continued to reproduce stereotypes and problematic tropes of victim-blaming. They routinely ignore relevant reporting guidelines.

Media reporting on the divisive Aziz Ansari case has produced both problematic and heartening results.

Read more: Yes means yes: moving to a different model of consent for sexual interactions

Taking a look at Australian reporting on this case, it was clear some articles excuse pressure and coercion as simply “the reality of sex” for women. One article even stated that “relenting can often mean consenting”. This reproduces problematic understandings of sex and gender relations, in which men are naturally aggressive initiators of sex, and women the passive gatekeepers of sexual activity.

However, some articles provided more nuanced reporting that recognised “relenting is not consent” and that:

more commonplace circumstances of coercion … account for a decent proportion of people’s traumatic sexual experiences.

This kind of reporting helps to unpack the complexities of sexual violence. It highlights that there are also harms associated with more everyday “grey area” behaviours.

As journalist Jane Gilmore’s “Fixed It” series that rewrites media headlines demonstrates, there is still a serious issue with the language the media use to talk about sexual violence. However, some #MeToo reporting shows a promising start in shifting discourse around sexual violence, opening up space for nuance and diversity in survivors’ experiences.

Social media and survivors speaking out

The #MeToo movement has also been significant online, with millions of survivors sharing their experiences on social media. Indeed, simply writing “me too” has become a shortcut for referencing an experience of sexual harassment or assault for survivors without having to say what actually happened.

This collective disclosure is a powerful act and should not be dismissed. Disclosing online can act as a kind of informal justice.

Online disclosure also allows survivors to seek support and act in solidarity with each other. It can help survivors to recognise their own experiences and realise they are not alone.

Mass disclosure through #MeToo also demonstrates the “magnitude of the problem” of sexual violence.

However, it is difficult to know what, if anything, has changed in the absence of any systematic analysis of #MeToo social media activity in Australia. Emerging international research suggests some survivors joined in #MeToo to draw attention to the political and structural nature of sexual violence and to challenge a perceived silence around this violence.

LGBTQ+ survivors in this study indicated they spoke out to ensure the experiences of these communities were included in #MeToo and to shift how we talk about sexual violence.

This suggests that involvement in #MeToo goes beyond simply sharing stories. Some survivors are able to articulate and draw attention to the underlying causes of sexual violence.

Yet it is equally true that social media continue to be a site of harm for women and gender-diverse people. It is implicated in the perpetration of sexual violence and misogyny as much as it is also a space for survivors to “speak out” about their experiences.

It is unclear whether or how this potential for backlash and online violence might shape how survivors talk about their experiences online. But it certainly influences whether they choose to disclose online.

Australia’s notoriously strict defamation laws have also limited how survivors can talk about their experiences. For example, it has been difficult for Australian survivors to “name and shame” their perpetrators as part of #MeToo.

We also need to be wary of making overly positive interpretations of survivors’ speaking out online. While it can be positive, it is not necessarily progressive.

For instance, survivor speech (and responses to that speech) circulating on social media that “goes viral” or gets picked up by mainstream media can sometimes reinforce stereotypes of what “real” sexual violence is. This was evident in some public responses to the Aziz Ansari case.

In speaking out, survivors may also call for punitive, criminal justice responses that reinforce other systems of oppression and power.

Speaking out about experiences has long been a staple part of anti-rape activism. But after nearly four decades of mobilisation on the issue, it seems survivors are continually having to speak out. And it is often similar voices that are heard: usually those of white, middle-class, heterosexual, and cisgender women.

The #MeToo movement has faced critique for replicating these gendered and racial divisions, suggesting that the movement is limited in its potential to create space for all survivors to be seen and heard. As such, the ways sexual violence is discussed on social media continue to represent only a limited range of experiences.

Moving forward from #MeToo

The progress and outcomes of social movements are almost always uneven. In the case of #MeToo, while this was indeed a watershed moment, there is still much to be done.

In particular, it is clear that while #MeToo has generated some change in what types of sexual violence are being discussed in social and mainstream media, and how, these shifts have been patchy at best.

Better training for journalists and editors reporting on sexual violence is one avenue to pursue. Social media platforms must also take more responsibility for moderating online misogyny (and other forms of hate speech) that perpetuates myths and problematic attitudes about sexual violence.

Read more: Politics with Michelle Grattan: Anne Summers on #MeToo and women in politics

The #MeToo movement demonstrated how widespread sexual violence is in our communities. This shocked and outraged many people. But the work of effectively responding to and addressing the causes of these experiences remains – and is the most challenging piece of this project.

The National Sexual Assault, Family & Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Authors: Bianca Fileborn, Lecturer in Criminology, University of Melbourne