the surprisingly swift end to evolution's big bang

- Written by Mike Lee, Professor in Evolutionary Biology (jointly appointed with South Australian Museum), Flinders University

The Cambrian explosion more than 500 million years ago is often considered biology’s “big bang”.

Virtually all the major kinds of animals evolved in life’s greatest ever burst of evolution, rapidly populating a weird and biologically sparse planet with everything from jellyfish to vertebrates, and turning it into the Earth we recognise today.

But our recent study, published this week in PNAS, shows this burst of rapid evolutionary innovation also ended surprisingly quickly.

Read more: New study confirms what scientists already know: basic research is under-valued

Animals took perhaps only 20 million years to fill most of the empty ecological niches (ways to make a living) on our entire planet. From then on, the pace of evolution slowed drastically, reverting to rates considered more normal and which have held sway for most of the subsequent 520 million years up to the present.

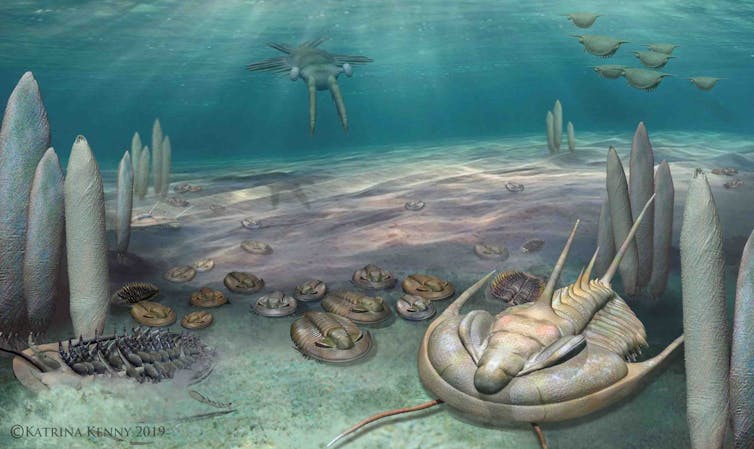

Cambrian seascape off South Australia, dominated by large (Redlichia) and small (Estaingia) trilobites.

Katrina Kenny, CC BY-NC-ND

Cambrian seascape off South Australia, dominated by large (Redlichia) and small (Estaingia) trilobites.

Katrina Kenny, CC BY-NC-ND

Our work suggests that evolution can fill even huge ecological vacuums extremely rapidly.

This has implications given the widespread global changes currently being wrought by humans. Ecological niches are being destroyed and created more rapidly than at any time since the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

The largest adaptive radiation of all time

Adaptive radiation is when a species finds itself surrounded by empty niches, and rapidly evolves into a range of different species with different lifestyles (such as herbivores or carnivores) to fill the entire vacuum.

As the environment becomes saturated, evolution gradually slows down to normal rates. Famous examples of adaptive radiation include marsupials in Australia and anole lizards in the Caribbean.

The biggest adaptive radiation of all is the Cambrian Explosion. Life first appeared at least 3.5 billion years ago, but for the subsequent 3 billion years little more than microbes and simple blobs existed.

At (or shortly before) the start of the Cambrian Period (541 million years ago), modern animals evolved. They rapidly diversified into all the major groups (phyla) of animals we see today, such as jellyfish and corals, segmented worms (such as earthworms), molluscs (such as snails), arthropods (such as crabs), and even vertebrates (backboned animals, which eventually included ourselves).

The strange-yet-familiar evolutionary products of the Cambrian period are exquisitely preserved in spectacular fossil sites around the world, such as the Burgess Shale in Canada and Chengjiang in China. Australia has its own: the Emu Bay Shale on Kangaroo Island.

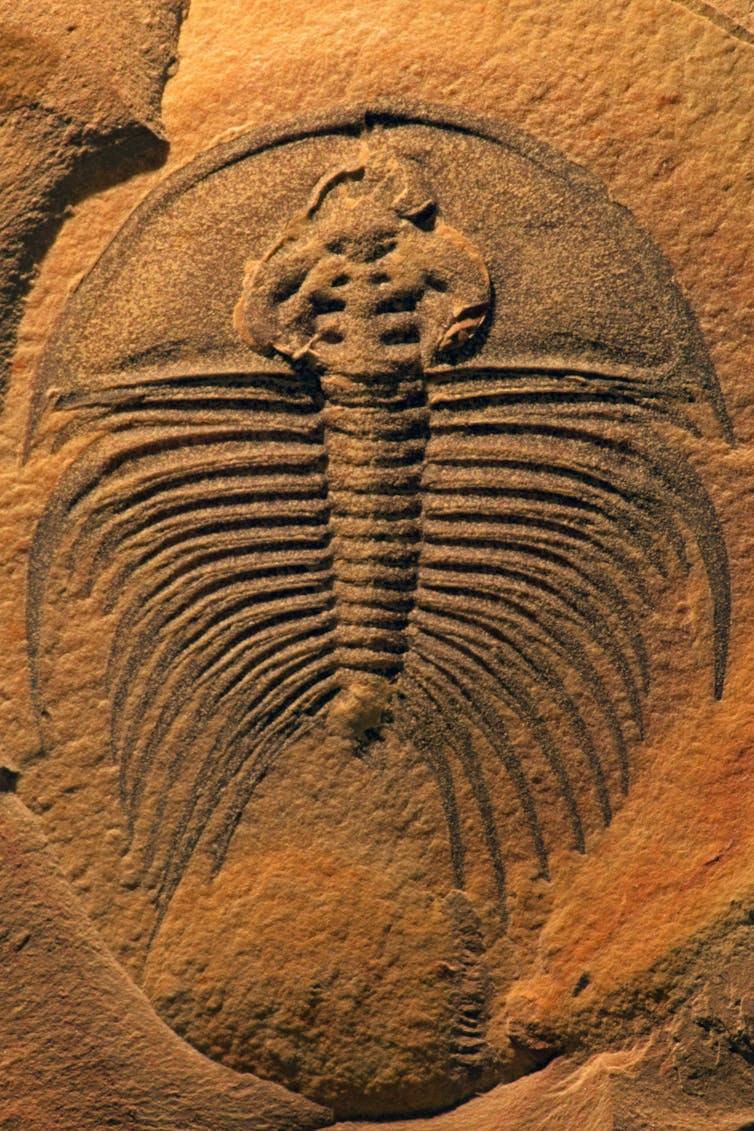

Trilobites (Estaingia) freshly excavated from Cambrian rocks (Emu Bay Shale) on Kangaroo Island.

John Paterson, University of New England, CC BY-NC-ND

Trilobites (Estaingia) freshly excavated from Cambrian rocks (Emu Bay Shale) on Kangaroo Island.

John Paterson, University of New England, CC BY-NC-ND

There is widespread agreement that evolution must have been turbocharged during the Cambrian explosion. But we didn’t really know for sure how long this unprecedented burst of rapid innovation and adaptation lasted.

If sustained across most of the Cambrian Period (which stretches from 541 million to 485 million years ago), then this would suggest that animals took more than 50 million years to fill up our planet.

Over in a (geological) eyeblink

Our study is the most thorough and mathematically precise measurement of evolution across the Cambrian Period.

Evolutionary rates are usually hard to calculate, partly because of the patchy fossil record. The complicated chain of events required for a dead organism to turn to stone means most carcasses are lost to time.

There are certainly rare instances where an evolving population is preserved across successively younger deposits, providing irrefutable evidence of evolution-in-action. More often, though, we find (say) a jaw bone in one place, followed by a limb bone on a different continent that is millions of years younger.

We circumvented the patchiness of the Cambrian fossil record in two ways. First, we focused on the dominant creatures of the Cambrian, the trilobites (an extinct group of marine arthropods related to other jointed-legged creatures like crabs, spiders and insects).

Trilobites are diverse and abundant (giving us a large and dense sample of fossils to work with), and also have very complex, robustly mineralised exoskeletons or “shells” (giving us lots of anatomical traits to measure).

Trilobites, such as this Olenellus, were the most diverse and abundant animals in the Cambrian.

Russell Bicknell, University of New England; Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, CC BY-NC-ND

Trilobites, such as this Olenellus, were the most diverse and abundant animals in the Cambrian.

Russell Bicknell, University of New England; Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, CC BY-NC-ND

Second, we used powerful new Bayesian methods called Markov-Chain Monte Carlo, which fully account for the uncertainty generated by missing data (such as gaps in the fossil record).

When faced with incomplete data, these methods don’t try to do the impossible and spit out a single precise answer. Rather, they cleverly infer the universe of probable answers given the fuzzy information at hand.

Our study reveals that evolution had subsided to the more normal rates within the early Cambrian – by at least 520 million years ago. Thus, the Cambrian explosion was over much earlier than many had suspected, indeed almost as soon as the first trilobites appeared.

If modern animals first evolved at the very beginning of the Cambrian, then their global adaptive radiation took a mere 20 million years.

While this is still substantial, it represents only 0.5% of the 3.5-billion-year history of life on Earth: a surprisingly brief interval to fill the Earth with body plans as disparate as starfish, snails, shrimps and fish.

Life finds a way

The rapid rise of animals suggested by our study emphasises the ability of evolution to quickly take advantage of every opportunity.

As the fictional mathematician Ian Malcolm put it in the first Jurassic Park (1993) movie, “life finds a way”!

The Cambrian explosion represented the first time animals evolved to fill the planet. Since then, several mass extinctions – such as the meteorite impact that contributed to the extinction the non-avian dinosaurs and much else – have partially cleared the decks.

Every time, life has rebounded rapidly.

Today, as humans transform and stress our planet, we are facing another mass extinction. Evolutionary niches are being destroyed and created at a rate faster than at any time since the dinosaur age.

The rapidity of evolution in the past might lead to optimism that life might adapt to the worst that humans can throw at it.

Read more: Climate change is killing off Earth’s little creatures

But this artificially rapid global change might be too fast for many species. Furthermore, much of the rapid evolution triggered by humans is far from desirable.

Swallows that evolve wingshapes to better manoeuvre through heavy traffic might be cute. But superbugs resistant to every known antibiotic, and subterranean mosquitos adapted to feast on London tube commuters, are less so!

A particularly vicious subspecies of mosquito has evolved on the London underground to bite humans.

francok35/pixabay

A particularly vicious subspecies of mosquito has evolved on the London underground to bite humans.

francok35/pixabay

Authors: Mike Lee, Professor in Evolutionary Biology (jointly appointed with South Australian Museum), Flinders University