The financially well-off defy the stereotypes. They include retirees, and mortgagees

- Written by David C. Ribar, Professorial Research Fellow, University of Melbourne

Financial well-being is hard to get a handle on.

That’s because it’s a mix of how people feel and how they objectively are.

And it’s multifaceted, including things such as spending, saving, investing, borrowing, and insuring, and competing goals that involve trade-offs, such as whether to spend or save.

To help, the Melbourne Institute and the Commonwealth Bank have pulled the dimensions together in a collection of measures we think are the first of their kind: the Reported and Observed Financial Well-being Scales.

The results released this week show most Australians are doing OK. They report no difficulty paying necessary expenses, can cover unexpected expenses, and feel on track to provide for their financial futures. However, a substantial minority struggle.

As expected, people’s income, assets, and home ownership play big roles in their financial well-being. But their attitudes, capabilities, and behaviour are probably even more important, meaning good financial well-being is possible even at modest levels of income and wealth.

Two ways of examining well-being

Adapting definitions that have been proposed for Australia and elsewhere, we define financial well-being as the extent to which people both perceive and have

- financial outcomes in which they meet their financial obligations

- financial freedom to make choices that allow them to enjoy life

- control of their finances, and

- financial security

now, in the future, and under possible adverse circumstances.

To construct the scales, we sieved through 33 self-reported survey measures and 17 bank-record measures that captured different elements of our definition. Formal analyis resulted in our two distinct but related scales.

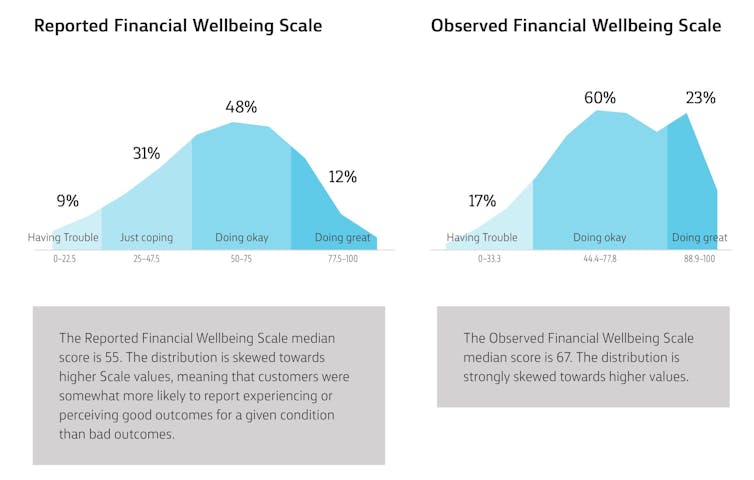

The first, which we call the CBA-MI Reported Financial Well-being Scale, uses people’s answers to 10 survey questions about how they feel; about things such as dealing with their expenses, building up savings, and control over their finances.

The second, which we call the CBA-MI Observed Financial Well-being Scale, uses data from people’s bank records about their balances, payment problems, and ability to cover unexpected expenses.

The two scales move together. People with high levels of financial well-being on one scale tend to have high levels on the other.

However, the two scales are distinct and capture different aspects of well-being, complementing each other and jointly providing a fuller picture than either could alone.

Melbourne Institute - Commonwealth Bank

What do the measures tell us?

On average, Australians enjoy moderate to high levels of financial well-being, but many experience problems. About a quarter of people report difficulty meeting their necessary expenses, and more than a third report not being able to handle a major unexpected expense or not having enough money for future financial needs.

When it came to characteristics associated with financial well-being, we find that people who earn more and own more assets enjoy higher well-being on average. Home-owners, healthier people, and married couples also tend to have a higher financial wellbeing. But within these categories financial well-being can vary.

Read more:

Why single women are more likely to retire poor

Both measures of well-being are higher for people who balance their spending and savings, have strong savings habits, always pay their credit card balances, sacrifice for the future, and actively plan and budget.

And there are surprises.

Retirees and older people tend to enjoy higher financial well-being than younger people, contrasting with the view that retirement is accompanied by financial distress.

People with high mortgage debt and large housing costs also experience higher levels of well-being, although this may be associated with the wealth that is associated with their homes.

Read more:

Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5%

The strong agreement between the two scales reassures us that they are indeed measuring financial well-being. However, the scales sometimes diverge, particularly when measuring the financial well-being of people with complex financial situations, including immigrants and business owners.

Improving financial well-being

The low levels of financial well-being experienced by some Australians are a cause for concern. Our measures can help identify these people and their circumstances.

More importantly, they tell us that people in similar circumstances can experience very different levels of financial well-being, telling us there is considerable scope for improving outcomes.

And the strong associations of well-being with financial attitudes, capabilities, and behaviours — all characteristics that can be changed — point to promising avenues for interventions.

Melbourne Institute - Commonwealth Bank

What do the measures tell us?

On average, Australians enjoy moderate to high levels of financial well-being, but many experience problems. About a quarter of people report difficulty meeting their necessary expenses, and more than a third report not being able to handle a major unexpected expense or not having enough money for future financial needs.

When it came to characteristics associated with financial well-being, we find that people who earn more and own more assets enjoy higher well-being on average. Home-owners, healthier people, and married couples also tend to have a higher financial wellbeing. But within these categories financial well-being can vary.

Read more:

Why single women are more likely to retire poor

Both measures of well-being are higher for people who balance their spending and savings, have strong savings habits, always pay their credit card balances, sacrifice for the future, and actively plan and budget.

And there are surprises.

Retirees and older people tend to enjoy higher financial well-being than younger people, contrasting with the view that retirement is accompanied by financial distress.

People with high mortgage debt and large housing costs also experience higher levels of well-being, although this may be associated with the wealth that is associated with their homes.

Read more:

Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5%

The strong agreement between the two scales reassures us that they are indeed measuring financial well-being. However, the scales sometimes diverge, particularly when measuring the financial well-being of people with complex financial situations, including immigrants and business owners.

Improving financial well-being

The low levels of financial well-being experienced by some Australians are a cause for concern. Our measures can help identify these people and their circumstances.

More importantly, they tell us that people in similar circumstances can experience very different levels of financial well-being, telling us there is considerable scope for improving outcomes.

And the strong associations of well-being with financial attitudes, capabilities, and behaviours — all characteristics that can be changed — point to promising avenues for interventions.

Authors: David C. Ribar, Professorial Research Fellow, University of Melbourne