The Uncomformity festival embraces the power and peculiarity of Tasmania's wild west

- Written by Asher Warren, Lecturer, University of Tasmania

Of the many festivals dotted across the island state of Tasmania, The Uncomformity is particularly well named. It is an inherently unique event, responsive to the particularities of the western town of Queenstown’s unique geology, ecology and culture.

Queenstown is nestled in Tasmania’s mountainous West Coast Range, between Mt Owen and Mt Lyell, with an infamous reputation for inclement weather. And it is remote: at least three hours of winding drive from both Hobart and Launceston.

On a sunny day, the views are spectacular; some for their natural beauty, others for the demonstrable effects of over a century of mining, smelting and clearing. However, after three days of immersion in the town and the festival, I began to feel that Queenstown was somehow better evoked by the moments when the clouds hung low, only to occasionally break open, revealing unexpected and surprising views.

A central ethos of The Unconformity is the curatorial commitment to site-specific and locally engaged work. Many of the works are unique to the location and the people of Queenstown, and developed by artists through multiple visits to the town. Note must be made of the exceptional diversity of gallery-based works, including Lucy Bleach’s enigmatic Variations on an Energetic Field and the overwhelming scale of Raymond Arnold’s survey, 100 Etchings/35 Years in Tasmania. But I was particularly struck by the use of performance within this festival, as a model for engaging with the place that is “Queenie”.

Queenstown’s bare hills were denuded by over a century of mining.

Shutterstock

Queenstown’s bare hills were denuded by over a century of mining.

Shutterstock

The power of listening

The pedestrian bridge over the town’s Queen River became a makeshift stall for audiences wearing headphones for Tasdance’s Junjeiri Ballun – Gurul Gaureima (Shallow Water, Deep Stories). Using the banks and the river itself, the bodies of five dancers explored the Indigenous history of the area and this waterway, which mine tailings and effluent once turned silvery grey and which remains, despite the remedial work to date, stained a remarkable shade of orange.

Tasdance’s Junjeiri Ballun – Gurul Gaureima.

The Uncomformity festival

Tasdance’s Junjeiri Ballun – Gurul Gaureima.

The Uncomformity festival

Across the bridge, Prospect brought Dylan Sherridan’s deft and thoughtful engagement with sound together with Sam Routledge’s knack for engaging dramaturgical structures. Using hacked metal detectors, and again wearing headphones, prospectors walked through Passion Park, searching for sonic treasures. The dynamic score was a delight, and the uneven experience for participants (some struck it richer than others) an interesting counterpoint to the otherwise even distributions created by works for headphones.

Another work experienced with headphones, A Score to Scratch the Surface (Opening Scene) by momo doto (Tom Blake and Dominique Chen), offers a markedly different take on the roaming soundscape.

Beginning in the dress circle of the 1933 Paragon Theatre, looking out at the projection screen, we hear an assemblage of recordings taken in and around Queenstown. Curious sonic artefacts are woven with brief snippets of conversations with locals, which slip in and out. The audience of three is ushered out of the theatre, into a car, and driven on a meandering tour of the town by a local resident. These stories, like the sites on this particular tour, don’t cry out for attention, forcing the ear and the eye to search for details. It’s a subtle and meditative work, which engages deftly with diverse reflections on the value of Queenstown’s natural resources.

As artist Tom Blake explained to me, the work was built slowly, over a number of visits to the town: “We were fortunate to have a development period that provided an opportunity to visit and revisit places and people over an extended period. We wanted to avoid being a flash in the pan – dropping by to make a work, then disappearing into the night.”

A Score to Scratch the Surface gestures toward the surprising paradoxes of Queenstown. It’s a place of riches, of devastation and resilience. With the mines closed since a tragic accident in 2013, and uncertainty about their reopening, the town sits in an uneasy limbo and faces difficult decisions. The challenges of regeneration – economically, environmentally and culturally – loom large. There are no easy answers, but the festival offers an opportunity to listen, to share and to understand something of this complexity.

Lucy Bleach’s Variations On An Energetic Field (Variation 3)

The Unconformity

Lucy Bleach’s Variations On An Energetic Field (Variation 3)

The Unconformity

While not explicitly noted as a theme for the festival, the act of listening seemed to be a particular focus. This was most explicit in Jill Orr’s durational performance Listening (made in collaboration with sound artist Richie Cyngler), staged in an old limestone quarry on the edge of town. This work asked audience members to record three wishes, while Orr, with characteristically otherworldly endurance, stood still and listened as these wishes were broadcast by loudspeakers and echoed around the quarry.

In the Medical Union building, Babel, directed by Glen Murray, allowed audiences to roam freely, exploring a panoply of other languages. While a remarkably simple conceit, the experience of wandering and listening to the diverse cast of performers was surprisingly compelling.

Starting with a bang

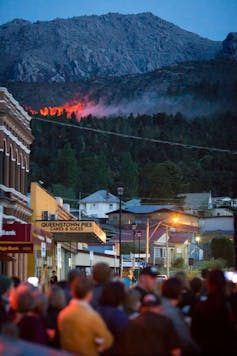

On a grander scale, the festival opened on Friday with Tectonica, a collaboration between Ian Pidd, Martyn Coutts and Dylan Sheridan, which closed down the main intersection to host a nine-tonne rock and some “bloody big speaker stacks”. The tremendous, visceral soundscape condensed some 500 million-odd years of geological activity into an hour of epic, quadrophonic sound and, in the distance, an ominous red fissure opened up in the mountainside. Not content to lie dormant, the speakers rumbled sporadically throughout the weekend, felt and heard throughout the small town.

Tectonica a display created by artists Martyn Coutts, Ian Pidd and Dylan Sheridan.

Unconformity festival

Tectonica a display created by artists Martyn Coutts, Ian Pidd and Dylan Sheridan.

Unconformity festival

The Falls, by Halcyon Macleod and Finegan Kruckemeyer, tells a story of young love, separation and return. It is a moving work, quite literally, as the audience dons headphones and climbs aboard a bus. The narrative of the play unfolds from a series of perspectives while journeying from one end of the Queen River – the Horsetail Falls – to the other, its confluence with the King River. It’s an ambitious and expansive work – and neatly staged – but at times the poetry of the script seemed to overextend, attempting to translate the narrative and connection to this site perhaps beyond its specifics.

An ominous red fissure opens in Tectonica.

Uncomformity

An ominous red fissure opens in Tectonica.

Uncomformity

Local works

For all the innovative contemporary work in this festival, and the influx of city slickers who pour in from Hobart (vying for the title of Australia’s new centre of hip) and the mainland, it would be all too easy to alienate the locals. But the festival does a remarkable job of keeping the West Coasters not only in the frame, but at the centre. While there was a palpable but subtle sense of reservation on the Friday night, by the closing Sunday the town seemed to reach a comfortable equilibrium.

Around noon on Sunday, after the ute muster took off and before the marquee football match on Queenstown’s notorious gravel oval, the bloody big speaker stacks gave a last hurrah and belted out a locally curated playlist of AC/DC’s greatest hits. An homage to the band’s 1976 performance in the town, the music slowly drew a crowd. It grew, as more joined in and danced around, and on, the rock left in the centre of the intersection.

This festival, which began as the Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival, and more recently reimagined as The Unconformity, has carved out a unique position in Tasmania and in Australia’s cultural landscape. It will next run in 2020, and its growing esteem and success raise an important question about growth and sustainability. One of the key features of this festival is its scale, which allows it to balance the influx of visitors and locals; they meet, rather than being overwhelmed.

Under proud West Coaster Travis Tiddy’s direction, however, the festival will hopefully approach its growth with the same focus and thoughtful reflection on place that made the 2018 version such a memorable success.

Authors: Asher Warren, Lecturer, University of Tasmania