diverting population growth to the regions

- Written by John Daley, Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute

This week we’re exploring the state of nine different policy areas across Australia’s states, as detailed in Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018. Read the other articles in the series here.

A dangerous fantasy is taking hold in Australia: that government policy can divert population growth from our bulging capital cities to our needy regions. It’s a fantasy because a century of Australian history shows it won’t work. And it’s dangerous because it gives governments an excuse to avoid the hard decisions on planning and transport needed to make housing more affordable and cities more liveable.

Since Federation, state and federal governments have tried to lure people, trade and business away from the capital cities. These efforts have mostly been expensive policy failures.

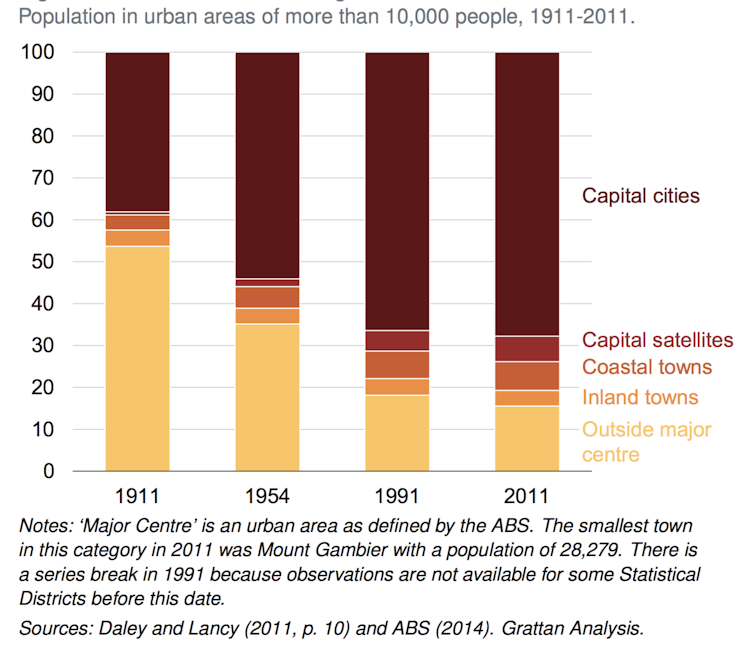

Despite substantial government spending on regional development aimed at promoting decentralisation, Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 shows the trend to city-centred growth has accelerated in the past decade. Less than a third of us now live outside the capital cities.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

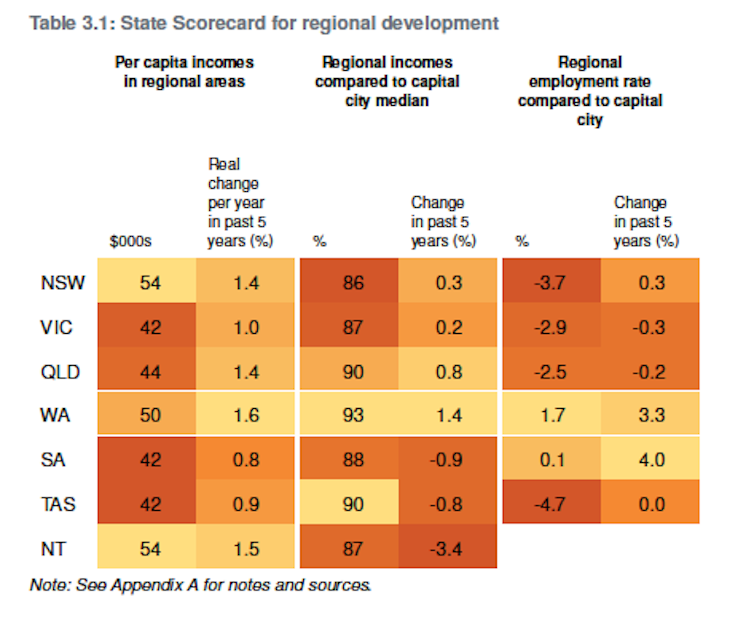

With the exception of Western Australian and Queensland mining regions, capital city economies over ten years have grown faster than regional economies. That’s mainly because their populations have grown faster.

Incomes per capita, on the other hand, have generally grown at about the same pace. Employment participation for women is similar too, although 25-to-64-year-old men in regions are 7% less likely to work than men in cities.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

With the exception of Western Australian and Queensland mining regions, capital city economies over ten years have grown faster than regional economies. That’s mainly because their populations have grown faster.

Incomes per capita, on the other hand, have generally grown at about the same pace. Employment participation for women is similar too, although 25-to-64-year-old men in regions are 7% less likely to work than men in cities.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

Why do most people choose to live in cities?

These are global trends. Large cities around the world are typically growing much faster than less densely populated areas. Even in Japan, where the national population is declining, Tokyo continues to grow.

The economic advantages of cities over regions appear to be increasing as people spend more of their incomes on services rather than goods. Services businesses often prefer to be close to other services businesses, typically in large cities.

Regional growth programs in Australia have a poor record of trying to push economic water uphill against these trends.

Take for example the New South Wales home buyers’ grant of $7,000 for people who move from cities to regions. Some 10,000 people were expected to take up the offer in the first year. In fact, only 4,800 grants were made over three years. Many of those probably went to people who would have moved anyway – perhaps to retire to “the bush”.

The key problem is that people will only move to regions if there are extra jobs. And policies to encourage more jobs in regional areas also have a poor track record. The money on offer from government is rarely enough to outweigh the economic advantages for a business of locating in a city instead.

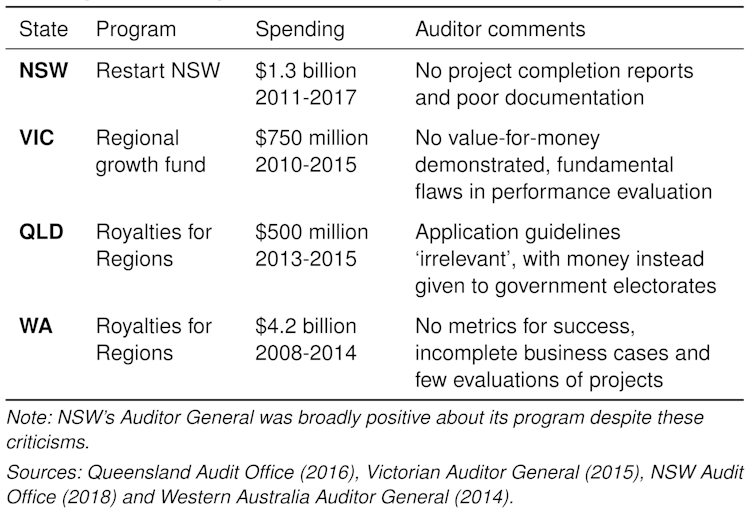

Most of the time we don’t even know whether regional development programs work because they are so badly administered. Auditors-general in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and WA have all found substantial regional development money being spent with no business case, or poor documentation, or without reference to application guidelines, and with no evaluation of whether the programs achieved the promised outcomes.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

Why do most people choose to live in cities?

These are global trends. Large cities around the world are typically growing much faster than less densely populated areas. Even in Japan, where the national population is declining, Tokyo continues to grow.

The economic advantages of cities over regions appear to be increasing as people spend more of their incomes on services rather than goods. Services businesses often prefer to be close to other services businesses, typically in large cities.

Regional growth programs in Australia have a poor record of trying to push economic water uphill against these trends.

Take for example the New South Wales home buyers’ grant of $7,000 for people who move from cities to regions. Some 10,000 people were expected to take up the offer in the first year. In fact, only 4,800 grants were made over three years. Many of those probably went to people who would have moved anyway – perhaps to retire to “the bush”.

The key problem is that people will only move to regions if there are extra jobs. And policies to encourage more jobs in regional areas also have a poor track record. The money on offer from government is rarely enough to outweigh the economic advantages for a business of locating in a city instead.

Most of the time we don’t even know whether regional development programs work because they are so badly administered. Auditors-general in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and WA have all found substantial regional development money being spent with no business case, or poor documentation, or without reference to application guidelines, and with no evaluation of whether the programs achieved the promised outcomes.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

The overwhelming impression is that governments don’t really want programs evaluated because they know all too well what the answers will be.

What if regional population policies did work?

In the unlikely event that government policy actually succeeded in encouraging many more people and employers to move to regional areas, it would probably slow growth in incomes. Cities are more productive, and this is reflected in higher wages.

Cities are important for innovation and economic growth. Cities offer more opportunities to share ideas, which both attracts skilled people and increases their skills once they arrive. Despite the rise of the internet and reduced telecommunication costs, innovation seems to rely on regular face-to-face contact between people in different firms, which therefore tend to aggregate in large cities.

So pushing extra people to regional areas runs the risk of reducing Australia’s productivity growth and per capita incomes.

So what about regional ‘dormitory’ suburbs?

Another strategy, much discussed in Victoria as it heads into a state election campaign, is to encourage the growth of regional towns as dormitory suburbs for people working in cities. Obviously this only works for regional towns that are relatively close to capital cities, with good transport links. Hence the big-spending promises to upgrade regional rail services.

But it is unclear why regional dormitories should be considered better than building suburbs on the city fringe. These fringe suburbs often provide access to more jobs in the other suburbs nearby.

In any case, the transport infrastructure needed to ferry people from homes in regional areas to jobs in the city is not cheap. Far better to relax planning laws to allow higher-density living where people want to live and can be close to a wide range of jobs – that is, in the established middle and inner suburbs of the capital cities.

The danger of distorted spending priorities

The fantasy that governments can divert population growth from cities to regions is also dangerous because it distorts spending priorities in regions. Government services probably improve regional lives more than government spending that is supposed to promote business growth. Government spending on regional arts and sports facilities probably has a much bigger impact per dollar than an extra kilometre of dual-lane highway.

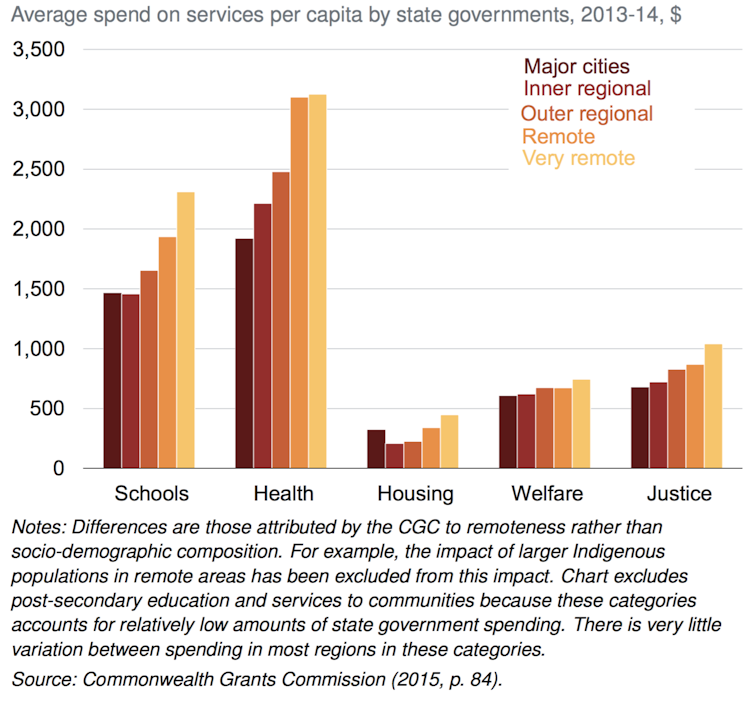

Government spending per person on education and health is in fact already higher in regions than in cities, even if service levels are often lower because they cost more to deliver. But if governments are going to spend more on regional services, the money may need to be spent differently.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

The overwhelming impression is that governments don’t really want programs evaluated because they know all too well what the answers will be.

What if regional population policies did work?

In the unlikely event that government policy actually succeeded in encouraging many more people and employers to move to regional areas, it would probably slow growth in incomes. Cities are more productive, and this is reflected in higher wages.

Cities are important for innovation and economic growth. Cities offer more opportunities to share ideas, which both attracts skilled people and increases their skills once they arrive. Despite the rise of the internet and reduced telecommunication costs, innovation seems to rely on regular face-to-face contact between people in different firms, which therefore tend to aggregate in large cities.

So pushing extra people to regional areas runs the risk of reducing Australia’s productivity growth and per capita incomes.

So what about regional ‘dormitory’ suburbs?

Another strategy, much discussed in Victoria as it heads into a state election campaign, is to encourage the growth of regional towns as dormitory suburbs for people working in cities. Obviously this only works for regional towns that are relatively close to capital cities, with good transport links. Hence the big-spending promises to upgrade regional rail services.

But it is unclear why regional dormitories should be considered better than building suburbs on the city fringe. These fringe suburbs often provide access to more jobs in the other suburbs nearby.

In any case, the transport infrastructure needed to ferry people from homes in regional areas to jobs in the city is not cheap. Far better to relax planning laws to allow higher-density living where people want to live and can be close to a wide range of jobs – that is, in the established middle and inner suburbs of the capital cities.

The danger of distorted spending priorities

The fantasy that governments can divert population growth from cities to regions is also dangerous because it distorts spending priorities in regions. Government services probably improve regional lives more than government spending that is supposed to promote business growth. Government spending on regional arts and sports facilities probably has a much bigger impact per dollar than an extra kilometre of dual-lane highway.

Government spending per person on education and health is in fact already higher in regions than in cities, even if service levels are often lower because they cost more to deliver. But if governments are going to spend more on regional services, the money may need to be spent differently.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

Grattan Institute analysis shows that poorer health and educational outcomes in some regional areas are primarily the result of socio-economic status and other risk factors – not remoteness. In health, for example, the substantial gap in mortality between regions and cities appears to result not from more distant hospitals but from people in regions tending to exercise less and have poorer diets.

Economic theory and policy experience, in Australia and other advanced economies, expose the “repopulate the regions” push as wishing thinking. As this series of articles based on Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 will show, there are better ways for governments to promote a growing Australia.

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018

Grattan Institute analysis shows that poorer health and educational outcomes in some regional areas are primarily the result of socio-economic status and other risk factors – not remoteness. In health, for example, the substantial gap in mortality between regions and cities appears to result not from more distant hospitals but from people in regions tending to exercise less and have poorer diets.

Economic theory and policy experience, in Australia and other advanced economies, expose the “repopulate the regions” push as wishing thinking. As this series of articles based on Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 will show, there are better ways for governments to promote a growing Australia.

Authors: John Daley, Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute