Modern Art from The Hermitage showcases the French gems of two great merchant collectors

- Written by Joanna Mendelssohn, Honorary Associate Professor, Art & Design: UNSW Australia. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, UNSW

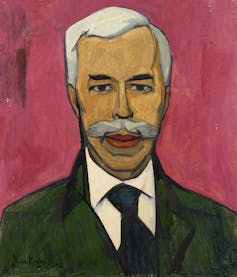

The first corner of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ summer blockbuster Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage is dominated by three giant black and white archival photographs, but visitors’ eyes are drawn to the intense colours of a single painting, Christian Cornelius Krohn’s 1915 portrait of the collector, Sergey Shchukin.

Unlike many of the great works in the Hermitage, which are very much a tribute to the collecting passion of Catherine the Great, most of the early 20th century paintings are a result of the collecting passion of two families – the Shchukins and the Morozovs.

Christian Cornelius Krohn (Xan Krohn) ‘Portrait of Sergey Shchukin 1915, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg Inv GE 9090.

© Estate of Christian Krohn/BONO.Copyright Agency, 2018

Christian Cornelius Krohn (Xan Krohn) ‘Portrait of Sergey Shchukin 1915, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg Inv GE 9090.

© Estate of Christian Krohn/BONO.Copyright Agency, 2018

Last year, much of Sergey Shchukin’s remarkable collection of early works by Picasso, Matisse and their circle, was shown in Paris. According to The Art Newspaper, French audiences packed the galleries as these were “some of the best paintings their culture has produced”. In Sydney, works from Shchukin’s collection mingle with paintings from the collection of the Morozovs, as well as other paintings “liberated” from their wealthy owners after the 1917 Revolution.

One of the photographs shows Shchukin’s Picasso room, where the walls are crowded with finely painted melancholy studies from the artist’s Blue Period, a few very early Cubist works – and two readily identifiable paintings from this exhibition.

Woman With a Fan and Farm Woman were both painted in 1908, when the artist was on the cusp of turning from Cézanne-inspired solid forms to Cubism. Woman With a Fan was loosely based on a study of his mistress, Fernande Olivier, while Farm Woman was based on Marie-Louise Putman, the owner of a house where Picasso was staying. Yet both have been rendered anonymous, reduced to pure geometry.

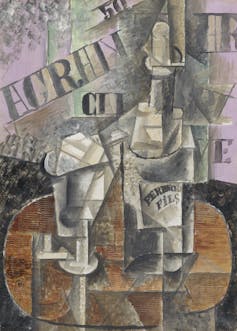

Pablo Picasso, ‘Table in a café (Bottle of Pernod)’ 1912 oil on canvas, 46 x 33 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 8920.

© Pablo Picasso/Succession Pablo Picasso/Copyright Agency 2018

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets

Pablo Picasso, ‘Table in a café (Bottle of Pernod)’ 1912 oil on canvas, 46 x 33 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 8920.

© Pablo Picasso/Succession Pablo Picasso/Copyright Agency 2018

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets

When the Shchukins and the Morozovs travelled to Paris for trade and pleasure they were following a path well trod by generations of Russians. Since the time of Peter the Great, Russia had turned to France for both intellectual and aesthetic nourishment. In music and dance this had long ceased to be one way traffic as Tchaikovsky melded elements from both Western and Russian traditions, while Russian Ballet took a French tradition and made it its own.

It is curious, but not surprising that the two great collectors of modern art were textile merchants. Their trade gave them an eye for fresh relationships between colour, line and texture.

By the end of the 19th century the Morozovs were one of the richest families in Russia. Ivan and Mikhail Morozov were passionate collectors of Bonnard, Sisley, Signac, Pissarro and Cézanne. The family was sympathetic to the aims of the Bolshevik Revolution (their grandfather had been a serf) and Ivan planned to eventually give his collection to the state.

Paul Cézanne, ‘Fruit’ 1879/80, oil on canvas, 46.2 x 55.3 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Inv GE 9026

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky

Paul Cézanne, ‘Fruit’ 1879/80, oil on canvas, 46.2 x 55.3 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Inv GE 9026

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky

But the state took it first. In 1923 his house and collection had become the State Museum of Modern Western Art, which eventually became the repository for looted art from other collections. By 1932, Stalin’s doctrinaire hegemony decreed that modern Western art was decadent and it vanished from public view until after his death. The preservation of Russia’s great collections in the face of totalitarian opposition is a tribute to the bravery of generations of dedicated museum professional staff.

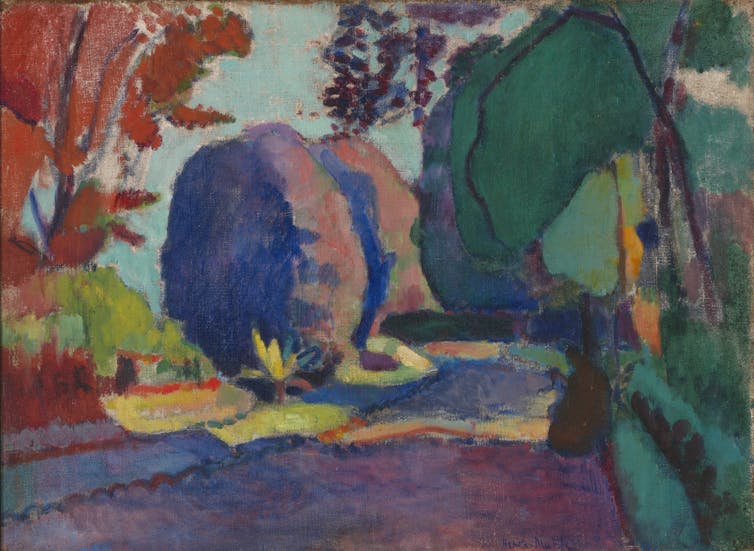

Sergey Shchukin, who first visited Paris in the 1890s, was a very early patron of that young radical, Henri Matisse. The earliest Matisse in this exhibition, The Luxembourg Gardens, circa 1901, takes a subject which is almost a cliché of French Impressionism, and makes it into a Fauve celebration of pure, intense colour.

Henri Matisse ‘The Luxembourg Gardens’ c1901, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg Inv GE 9041.

© Succession H Matisse/Copyright Agency, 2018

Henri Matisse ‘The Luxembourg Gardens’ c1901, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg Inv GE 9041.

© Succession H Matisse/Copyright Agency, 2018

It is a truly remarkable painting. Shchukin bought it from Matisse’s dealer, Galerie Druet, in 1907. A year later he bought the luminous Woman on a Terrace of 1906, a work of such stunning simplicity that it is worth seeing the exhibition for this alone. But Shchukin did not stop with collecting Matisse’s early masterpieces and befriending the artist. In 1911 Matisse visited Russia, as Shchukin’s guest.

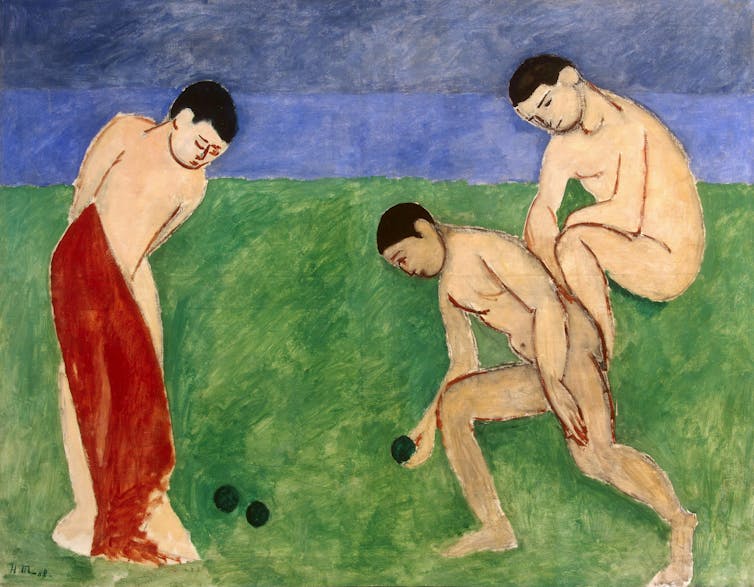

The portrait of Shchukin hangs next to an entrancing, but frustrating, photograph of the Pink Drawing Room in his mansion. The elaborate 18th century Roccoco room is covered in a crowd of masterpieces by Matisse - but the photograph is in black and white, with no sense of colour. From historic records we know that in order to prepare the room for his art, the artist arranged for the ceiling to be painted pink. The walls were given pale green wallpaper, the carpet was cherry red. Matisse then curated his personal selection of some of the paintings Shchukin had bought, including A Game of Bowls of 1908.

Henri Matisse ‘Game of bowls’ 1908, oil on canvas, 115 x 147 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9154.

© Succession H Matisse/Copyright Agency, 2018

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg 2018, Vladimir Terebenin

Henri Matisse ‘Game of bowls’ 1908, oil on canvas, 115 x 147 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9154.

© Succession H Matisse/Copyright Agency, 2018

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg 2018, Vladimir Terebenin

I can understand why this work, along with Nymph and Satyr, painted the following year, hangs at the entrance to the central court in the Sydney exhibition. Their fluidity of form and line, along with their limited palette, connect them to Matisse’s two great Dance and Music paintings.

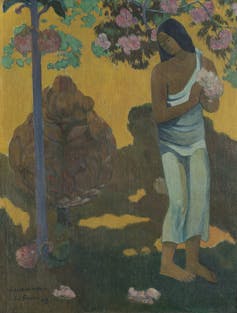

Paul Gauguin,‘The month of Mary (Te avae no Maria)’ 1899, oil on canvas, 96 x 74.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 6515.

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets

Paul Gauguin,‘The month of Mary (Te avae no Maria)’ 1899, oil on canvas, 96 x 74.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 6515.

Photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets

The opportunity to see this art up close and personal, to get a sense of how Matisse interacted with the culture of the man who so admired him, is rare indeed.

The Dance and Music paintings are not in the Sydney show. However, visitors can see Peter Greenaway and Saskia Boddeke’s five channel, multi-media installation that recreates the relationship between Shchukin, Matisse, radical Russian artists and two of the great paintings of the 20th century.

Shchukin was passionate about sharing the art he had bought. In 1907 he opened his house to visitors every Sunday. When the Bolshevik Revolution overturned the old order in 1917, he fled to France and his art was seized on the orders of Lenin.

The last work in the exhibition, Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, owes nothing and everything to the activities of the merchant collectors of modern art. In its stark denial of any resemblance to reality, it eliminates any consideration of possible decoration and challenges the very idea of what art may be.

The first version of Black Square was exhibited in St Petersburg in 1915 in the The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10. It therefore overlaps between the era of the merchant collectors and the creation of a new world.

If there had been no Revolution, no state confiscation of this great collection, would it have remained intact, or would it have been fragmented by the relentless art market?

The actions of the first Bolshevik revolutionaries, followed by the ethical scholarship and fortitude of generations of curators, enable us today to have a small window into the minds of these great experimental collectors and the art that they loved.

Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until March 3.

Authors: Joanna Mendelssohn, Honorary Associate Professor, Art & Design: UNSW Australia. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, UNSW