Gender diversity is more accepted in society, but using the pronoun 'they' still divides

- Written by Son Vivienne, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, RMIT University

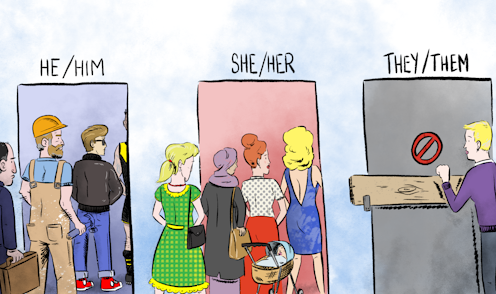

In recent months, there has been much heated discussion about the way gender-neutral pronouns (they, them, theirs) are being introduced as alternatives to the more conventional “he” and “she” in offices, schools and public institutions.

Earlier this year, for instance, Qantas encouraged staff to adopt gender-inclusive language with customers, using the term “partner” instead of “husband” or “wife”.

The Victorian state government backed a similar initiative for public servants and launched a “They Day” campaign on the first Wednesday of each month to encourage awareness of gender-neutral pronouns.

And last year, the Australian Defence Force issued a guide with recommendations on how to appropriately address gender-diverse members of the force.

Some critics argue that these language changes are radical and politically motivated, and are being forced upon unwilling employees.

After the ADF launched its guide on gender-neutral language choices, The Telegraph claimed the organisation was banning the use of “him” and “her” – an assertion the ADF quickly dismissed.

Australian universities were also forced to defend the launch of similar guides for staff and students after another Telegraph story accused them of banning the words “mankind” and “manpower”.

There’s been vocal opposition to these moves from Liberal leaders, as well. The new deputy leader, Josh Frydenberg, dismissed “They Day” as “political correctness gone mad”, while Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton decried “invading the minds of young people with this sort of garbage message.”

Increasing acceptance in society

Guides for respectful and inclusive language protocols are not new, nor are they aimed at erasing existing gender-specific pronouns.

The debate over gender-neutral language actually dates back to the mid-1980s, when ungendered job titles became more popular (for example, “firefighters” instead of “firemen”) and the pronouns “he/she” or “they” began appearing in texts instead of default “he” when the gender of the person being referred to is not known.

In recent years, the use of the pronoun “they” to refer specifically to non-binary people has become increasingly accepted by media outlets. The Washington Post, for example, updated its style guide in 2015 to include singular “they” for people who identify as neither male or female. The New York Times has introduced the new honorific Mx. And the Associated Press followed with its own change to the venerable AP Stylebook last year.

Not only does incorporating gender-neutral pronouns into the public sphere allow for more inclusivity, it can also bring standardisation to government functions, such as official documents and surveys (such as the census).

This enables more accurate self-identifications and brings greater visibility to previously unseen (and uncounted) groups of gender-diverse people.

The 2016 census was the first to allow an option for gender other than male or female on a special online form. The ABS provided the online form to a pilot group of 30,000 households to test their reactions. Gender-diverse people outside the pilot group were also able to access the form, but only if they sought it out on their own.

In total, 1,260 people in Australia were counted as gender diverse, but the ABS acknowledges this was probably lower than the actual figure due to fear of stigma and lack of widespread awareness over the new self-identifying option.

Still, the ABS found people in the pilot were over 50 times as likely as those outside the pilot to identify as gender diverse. Arguably, this suggests that simply offering the new option will provide an incentive for all gender-diverse people to choose how they are categorised and counted.

Higher counts in other surveys

Perhaps not surprisingly, there’s increasing acceptance of gender diversity among young people. In the US, a 2017 report by GLAAD indicated that 12% of Millennials (aged 18-35) identify as transgender or gender non-conforming – double the percentage of people in Generation X (people aged 35-51).

In 2016, research by the trend-forecasting Innovation group also found that 56% of American Gen Zers (aged 13-20) know someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns.

In our 2016 national survey of more than 1,200 young people aged 16-35, we found a proliferation of gender-diverse identities on online platforms like Tumblr, where discussion of gender non-conformity is the norm and the possibility of curating multiple identities is routine.

Overall, 20% of our participants identified as non-binary or chose to define their own gender identities as “other” than male or female.

Slowly adapting bureaucracy

Despite these changes, some workplaces, schools and social service providers have been slow to embrace change and provide exclusive spaces for gender-diverse people.

For example, bathrooms remain overwhelmingly binary and inflexible. Part of the problem are inconsistencies in the laws and policies at the state and national level and between organisational stakeholders. For example, sporting bodies such as AFL, NRL and Cricket Australia defer to individual venues to make decisions on gender-neutral spaces.

There are obstacles to accommodating gender diversity in official identification documents, as well. In Australia, we have a mix of approaches for gender registration, with passports and marriage certificates dealt with at the Commonwealth level, while birth certificates are issued by states and territories.

Gender-diverse people have been able to choose an “X” category in passports since 2013 (with supporting documentary evidence from a doctor or psychologist). But changing one’s gender on birth certificates is still only possible in ACT, NSW and SA. (It’s also currently being debated in Queensland.)

These difficulties in reconciling different forms of identification can act as barriers to employment, accessing medical treatment and higher education and travelling internationally.

Social change can be facilitated by making new categories available, whether that’s in architectural design (gender-neutral bathrooms) or digital infrastructures (non-binary options for official documents and surveys).

Using the pronoun “they” or allowing for more gender options in the public sphere isn’t political correctness gone awry. It’s just a small shift in the evolution of how we understand, categorise and define gender.

Most people inhabit multiple identities during their lives, such as daughter, student, professional and mother. The contradictions between some of these categories are evident in our online profiles - for example, we display a different version of ourselves on LinkedIn compared with Facebook or Instagram.

Gender is just another type of identity. We shouldn’t restrict this to binary terms, but rather embrace the diversity of all the perfectly valid “in-betweens”.

Authors: Son Vivienne, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, RMIT University