Morrison's return to surplus built on the back of higher tax – Parliamentary Budget Office

- Written by Saul Eslake, Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow, University of Tasmania

First, the good news. The Parliamentary Budget Office’s latest medium-term budget projections provide independent reassurance that the government’s personal income tax cuts, announced in the May budget and passed through parliament in June, can be funded without pushing the budget back into deficit.

But they also sound warnings about the downside risks from weaker-than-assumed economic or wages growth, and from any relaxation of the spending restraint that successive governments have maintained since 2012.

More income tax

The PBO projects the federal government’s “underlying” cash balance to improve from 0.8% of GDP in 2021-22, the last year of the latest budget’s forward estimates period, to 1.3% of GDP in 2028-29.

Read more: Budget policy check: does Australia need personal income tax cuts?

That’s after allowing for the revenue forgone by the tax cuts. Without these, and in the absence of any other spending or revenue measures, the surplus would have reached 3.7% of GDP (my calculation, not the PBO’s), largely on the back of the “bracket creep” that would have occurred without some form of personal income tax cuts between now and then.

Even so, there’s an awful lot of bracket creep.

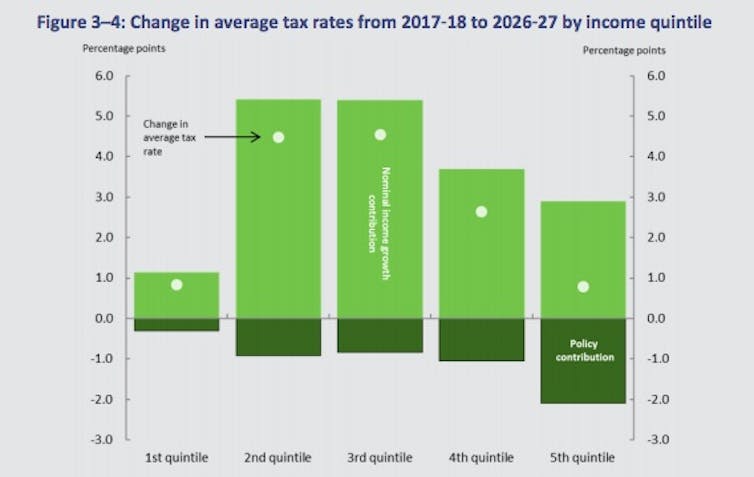

Projected change in average income tax rates by quintile.

Parliamentary Budget Office, 2018-19 Budget: Medium-Term Projections (September 2018), CC BY

Projected change in average income tax rates by quintile.

Parliamentary Budget Office, 2018-19 Budget: Medium-Term Projections (September 2018), CC BY

The average tax rate across all taxpayers is projected to increase from 22.9% to 25.2% – that is, by 2.3 percentage points. For taxpayers in the second and middle quintiles (the middle fifth and the second-to-bottom fifth) it’s even worse. They will see their average rates rise by more than 4 percentage points. The average tax rate for those in the top and bottom quintiles will climb by less than 1 percentage point.

The PBO’s projections allow for only slight additional relief; small reductions in 2027-28 and 2028-29, worth about 0.4% of GDP, to ensure tax receipts remain within the government’s “cap” of 23.9% of GDP in the final two years of the 10-year projection period.

A helpful backdown on company tax

The PBO’s forecasts don’t allow for the government’s recent decision to abandon the previously proposed cut in the corporate tax rate for companies with annual turnover exceeding $50 million, which it had been unable to pass through the Senate. That would add the equivalent of almost 0.5 of a percentage point of GDP to the surplus by 2028-29, unless offset by other measures (which it probably will be).

Read more: The full story on company tax cuts and your hip pocket

By law, the PBO is required to use the same economic assumptions in framing its medium-term projections as those used in the most recent federal budget.

Wishful economic thinking

These requirements mean the projections are conditioned on, among other things, “above-trend economic growth for much of the period” and “a return to close to trend wages growth” by 2021-22.

This week’s national accounts data lend some near-term support to the first of these assumptions, but they (and other data) cast further doubt on the likelihood of wages growth returning to trend in line with the budget assumptions.

Read more: This is what policymakers can and can't do about low wage growth

The PBO notes that, as a direct result of the government’s personal income tax plan, any weakness in future tax receipts flowing from “weaker economic circumstances” will “flow through directly to the budget bottom line”.

A decade of tight spending

The report highlights the importance of policy decisions in stemming the flow of new spending decisions and tightening eligibility for benefit payments since 2012.

Much of the impact of these will show up more clearly over the next decade. Apart from three areas – the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), aged care and defence, on which spending is projected to rise by a little over 1 percentage point of GDP over the next decade – other government spending is projected to fall by around 2 percentage points of GDP between 2017-18 and 2028-29.

Read more: Government spending explained in 10 charts; from Howard to Turnbull

The PBO notes that “the spending restraint seen over the past few years … may be increasingly difficult to maintain with an improving budget outlook”.

(Unintentionally) highlighting that risk, the PBO explicitly notes that the proposed further increase in the pension eligibility age to 70 between 2023 and 2035 – which the government abandoned this week – was “projected to have a significant impact on Age Pension spending … over the next decade”.

Authors: Saul Eslake, Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow, University of Tasmania