how the Islamic State honours its fallen soldiers – and how Australians do the same

- Written by Mark Alfano, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Delft University of Technology

The belief that we must not let our soldiers “die in vain” dates back to ancient Athens. During the Peloponnesian War, Pericles delivered a funeral oration in which he urged his compatriots to see themselves in the heroism of recently deceased fighters. Honouring these heroes, he argued, required continuing the struggle with Sparta. The living could prove themselves worthy of the sacrifice of the dead only by fighting for what they fought for and embodying the virtues (such as courage) they embodied.

In modern times, political scientists have argued that it is “important to say of those who died in war that they did not die in vain”. This notion was echoed by US President George W. Bush when he suggested that the people killed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks “did not die in vain”.

And, just like Pericles, Bush suggested the best way to prove that deaths in the so-called war on terror were not in vain was to continue the conflict. In this way, war becomes an end in itself. The fighting may never cease because there is always one more soldier to honour, one more civilian casualty to avenge.

Through a glass, darkly

The way people talk about the dead and the traits they hope to manifest by way of honouring them tell us what counts as a virtue in their community. In my previous research, I’ve show that different communities celebrate their dead in different ways. Most of my work has focused on civilians, but I recently began to investigate what is said about combatants killed in action.

One interesting and troubling comparison is between the obituaries of Western soldiers who have been killed in the Middle East and those of Islamic State fighters.

Read more: Must love jokes: why we look for a partner who laughs (and makes us laugh)

Here’s a little quiz: which of the following traits are associated with IS “martyrs” and which with Australians recently killed in action in Afghanistan, Iraq and nearby countries?

- dedicated

- steadfast

- respected

- patient

- humorous

- brave

- a leader

- humble

- inspiring

- loyal

The truth is that most of these traits are associated with both populations. To establish this, I coded every obituary published by the Islamic State in its two online magazines, Dabiq and Rumiyah, along with a matching sample of obituaries published in Vale by the Australian Department of Defence.

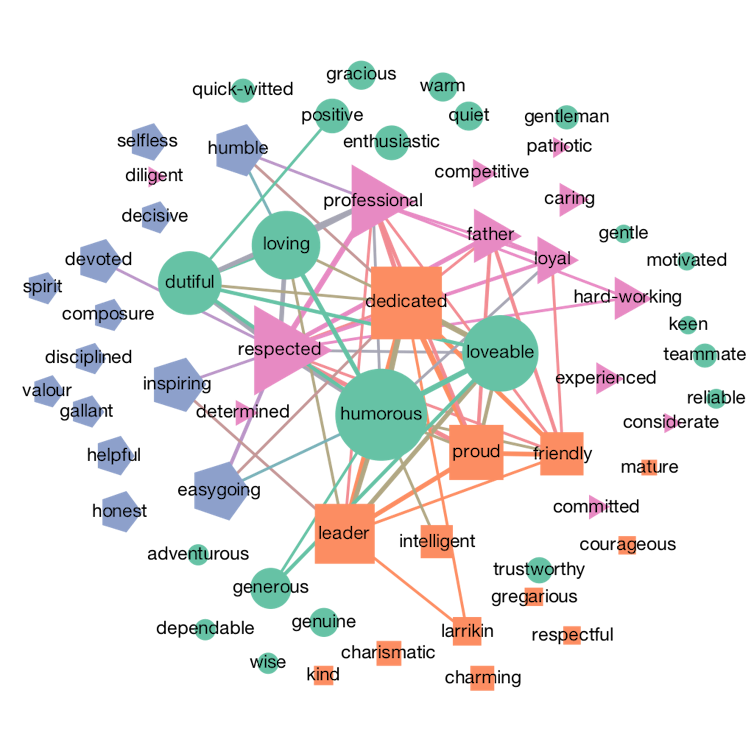

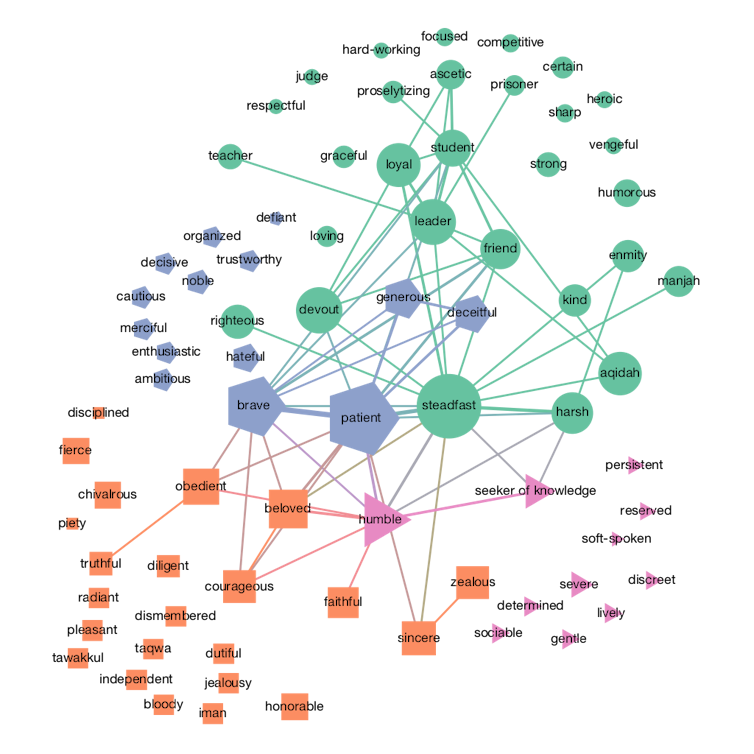

I then mapped out the patterns of co-occurrence among traits to see which virtues are associated with combatants in each community. Here’s what the Australian Department of Defence and IS have to say about their war dead:

Australia conflict obituaries.

Australia conflict obituaries.

ISIS conflict obituaries.

ISIS conflict obituaries.

Both the IS and the Australian data are available for examination. What these texts tell us is that ISIS and the Australian government speak of their dead in similar ways. And both use the occasion of martial grief to motivate the continuation of conflict. In so doing, they place death in the context of an ongoing narrative or trajectory that points to further violence as the only acceptable option.

There are, of course, some differences. Australian soldiers are more likely to be remembered as professional, easygoing and larrikin. IS fighters are more likely to be remembered as ascetic, deceitful and harsh (towards enemies – not in general). Their obituaries tend to refer to religious concepts such as aqidah (adherence to correct creed), manhaj (theological insight), and taqwah (pious humility).

These terms refer to values of the local community just as much as “larrikin” does for Australians. And IS fighters are praised not just for their religious or theological virtues but also for traits we find more familiar and congenial. Even someone as the bloody-minded as “Jihadi John” (Mohammed Emwazi) was praised in his obituary for his sense of humour.

Moreover, just as the obituaries published in Dabiq and Rumiyah tend to call others to continue the struggle, so the obituaries published in Vale often include and even conclude with calls to action. In one, the deceased soldier’s commanding officer declares:

We will honour his sacrifice by finishing what he helped us to start.

In another, the decedent’s family concludes that he “would want his colleagues to keep fighting the cause”.

From monuments to memorials

The philosopher Arthur Danto has suggested we “erect monuments so that we shall always remember, and build memorials so that we shall never forget”. Monuments express a community’s pride and commitment to victory; memorials express a community’s remorse and commitment to redress.

Monuments to those who die in battle also encourage and sometimes demand the interminable renewal of conflict. Even if it makes us queasy to recognise our shared humanity with killers as deeply evil as Jihadi John, perhaps a shift from monumentalising our war dead to memorialising them is necessary. Otherwise, we stand the risk of becoming what we rightly despise.

Authors: Mark Alfano, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Delft University of Technology