How the moral lessons of To Kill a Mockingbird endure today

- Written by Anne Maxwell, Assoc. Professor, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne

In our series, Guide to the classics, experts explain key works of literature.

Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird is one of the classics of American literature. Never out of print, the novel has sold over 40 million copies since it was first published in 1960. It has been a staple of high school syllabuses, including in Australia, for several decades, and is often deemed the archetypal race and coming-of-age novel. For many of us, it is a formative read of our youth.

Read more: 'Great books', nationhood and teaching English literature

The story is set in the sleepy Alabama town of Maycomb in 1936 - 40 years after the Supreme Court’s notorious declaration of the races as being “separate but equal”, and 28 years before the enactment of the Civil Rights Act. Our narrator is nine-year-old tomboy, Scout Finch, who relays her observations of her family’s struggle to deal with the class and racial prejudice shown towards the local African American community.

Among Lee’s accolades were her 2007 Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Shawn Thew/AAP

Among Lee’s accolades were her 2007 Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Shawn Thew/AAP

At the centre of the family and the novel stands the highly principled lawyer Atticus Finch. A widower, he teaches Scout, her older brother Jem, and their imaginative friend Dill, how to live and behave honourably. In this he is aided by the family’s hardworking and sensible black housekeeper Calpurnia, and their kind and generous neighbour, Miss Maudie.

It is Miss Maudie, for example, who explains to Scout why it is a sin to kill a mockingbird: “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us.”

Throughout the novel, the children grow more aware of the community’s attitudes. When the book begins they are preoccupied with catching sight of the mysterious and much feared Boo Radley, who in his youth stabbed his father with a pair of scissors and who has never come out of the family house since. And when Atticus agrees to defend Tom Robinson, a black man who is falsely accused of raping a white woman, they too become the target of hatred.

A morality tale for modern America

One might expect a book that dispatches moral lessons to be dull reading. But To Kill a Mockingbird is no sermon. The lessons are presented in a seemingly effortless style, all the while tackling the complexity of race issues with startling clarity and a strong sense of reality.

Read more: William Faulkner diagnosed modern ills in As I Lay Dying

As the Finches return from Robinson’s trial, Miss Maudie says: “as I waited I thought, Atticus Finch won’t win, he can’t win, but he’s the only man in these parts who can keep a jury out so long in a case like that.”

Despite the tragedy of Robinson’s conviction, Atticus succeeds in making the townspeople consider and struggle with their prejudice.

Atticus Finch delivers his closing statement in the trial of Tom Robinson in the 1962 film.The effortlessness of the writing owes much to the way the story is told. The narrator is a grown Scout, looking back on her childhood. When she begins her story, she seems more interested in telling us about the people and incidents that occupied her six-year-old imagination. Only slowly does she come to the events that changed everything for her and Jem, which were set in motion long before their time. Even then, she tells these events in a way that shows she too young to always grasp their significance.

The lessons Lee sets out are encapsulated in episodes that are as funny as they are serious, much like Aesop’s Fables. A case in point is when the children return home from the school concert with Scout still dressed in her outlandish ham costume. In the dark they are chased and attacked by Bob Ewell the father of the woman whom Robinson allegedly raped. Ewell, armed with a knife, attempts to stab Scout, but the shapeless wire cage of the ham causes her to loose balance and the knife to go astray. In the struggle that ensues someone pulls Ewell off the teetering body of Scout and he falls on the knife. It was Boo Radley who saved her.

Another lesson about what it means to be truly brave is delivered in an enthralling episode where a local farmer’s dog suddenly becomes rabid and threatens to infect all the townsfolk with his deadly drool.

Scout and Jem are surprised when their bespectacled, bookish father turns out to have a “God-given talent” with a rifle; it is he who fires the single shot that will render the townsfolk safe. The children rejoice at what they consider an impressive display of courage. However, he tells them that what he did was not truly brave. The better example of courage, he tells them, is Mrs Dubose (the “mean” old lady who lived down the road), who managed to cure herself of a morphine addiction even as she was dying a horribly painful death from cancer.

The courthouse in Lee’s hometown, Monroeville, upon which Maycomb was modelled.

Dan Anderson/AAP

The courthouse in Lee’s hometown, Monroeville, upon which Maycomb was modelled.

Dan Anderson/AAP

He also teaches them the importance of behaving in a civilised manner, even when subjected to insults. Most of all Atticus teaches the children the importance of listening to one’s conscience even when everyone else holds a contrary view: “The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule”, he says, “is a person’s conscience.”

The continuing value in Atticus’ belief in the importance of principled thinking in the world of Black Lives Matter and the Australian government’s rhetoric of “African gangs”, is clear.

Atticus’ spiel on “conscience” and the other ethical principles he insists on living by, are key to the enduring influence of the novel. It conjures an ideal of moral standards and human behaviour that many people still aspire to today, even though the novel’s events and the characters belong to the past.

Lee herself was not one to shy away from principled displays: writing to a school that banned her novel, she summed up the source of the morality her book expounds. The novel, she said, “spells out in words of seldom more than two syllables a code of honor and conduct”.

Fame and obscurity

When first published the novel received rave reviews. A year later it won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature, followed by a movie version in 1962 starring Gregory Peck. Indeed, the novel was such a success that Lee, unable to cope with all the attention and publicity, retired into obscurity.

Interviewed late in life, Lee cited two reasons for her continued silence: “I wouldn’t go through the pressure and publicity I went through with To Kill a Mockingbird for any amount of money. Second, I have said what I wanted to say, and I will not say it again.”

The latter statement is doubtless a reference to the autobiographical nature of her book. Lee passed her childhood in the rural town of Monroeville in the deep south, where her attorney father defended two black men accused of killing a shopkeeper. The accused were convicted and hanged.

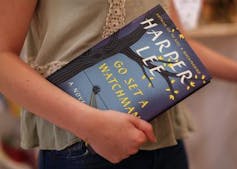

Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman met with a mixed reception.

Erik Lesser/AAP

Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman met with a mixed reception.

Erik Lesser/AAP

Undoubtedly influenced by these formative events, the biographical fiction Lee drew out of her family history became yet more complex upon the publication of her only other novel, Go Set a Watchman, in 2016. Critics panned it it for lacking the light touch and humour of the first novel. They also decried the fact that the character of Atticus Finch was this time around a racist bigot, a feature that had the potential to taint the author’s legacy.

Read more: Review/ Has Go Set a Watchman helped topple the notion of the white saviour?

Subsequent biographical research revealed that Go Set A Watchman, was not a sequel, but the first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird. Following initial rejection by the publisher Lippincot, Lee reworked it into the superior novel many of us know and still love today.

Lee gave us the portrait of one small town in the south during the depression years. But it was so filled with lively detail, and unforgettable characters with unforgettable names like Atticus, Scout, Calpurnia and Boo Radley that a universal story emerged, and with it the novel’s continuing popularity.

Authors: Anne Maxwell, Assoc. Professor, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne

Read more http://theconversation.com/how-the-moral-lessons-of-to-kill-a-mockingbird-endure-today-100763