how Romanticism rebelled against cold-hearted rationality

- Written by Matthew Ryan, Lecturer in Literature, Australian Catholic University

Romanticism is often fixed within a period running from the late-18th to early-19th century. But Romanticism as a cultural movement and as a set of ideas influencing visual art, literature, philosophy and politics, bleeds out beyond these designated boundaries.

Indeed, its influence continues in the 21st century. When we think about the qualities of imagination, the natural world or the composition of the self, we usually call upon an idea or two from what has come to be known as Romanticism.

In 21st-century culture, Romantic ideas usually appear when the human and the natural worlds are brought together. For example, the novels of Peter Carey or Tim Winton sometimes set up a type of metaphysical resonance between landscape and the formation (or dissipation) of the self.

Or, we see a fantasy of our integration with nature (tinged with Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “nascent humanity”) in James Cameron’s film Avatar. Even the feedback loop of depression and apocalypse that appears in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, owes something to Romanticism.

The term “Romanticism” derives from the attraction of some 18th-century German and English thinkers to the culture of the Middle Ages. “Romance” - such as that exhibited in the 13th-century French stories of King Arthur- provided a model of imaginative non-realism, intensity of feeling and decisiveness of action that appealed to young artistic rebels. The Middle Ages also offered an imagined community of integrated harmony that contrasted with the transformations and tumult of late 18th-century Europe.

Read more: Guide to the classics: the Arthurian legend

Often, Romanticism is seen as a counterpoint to the Enlightenment. In 1784, Immanuel Kant suggested a slogan for the Enlightenment: “Have courage to use your own understanding!” This prompted the question: what is the nature of that understanding?

Wikimedia Commons

The modern world can still be understood as swinging between, on one side, the cool work of quantification and observation in scientific rationality and, on the other, a desire for the heat of life lived with intensity, in the experience of emotion or of the ineffable. These latter qualities we find in imaginative and freedom-loving Romanticism, which made a home for itself in English poetry.

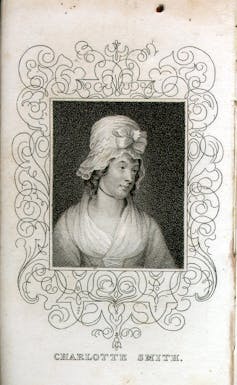

Poets such as Charlotte Smith, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Clare presented artistic critiques of what they saw as the exploitative and cold-hearted rationality of their times. These English poets found a refuge for their idea of free and creative humanity in nature and the imagination.

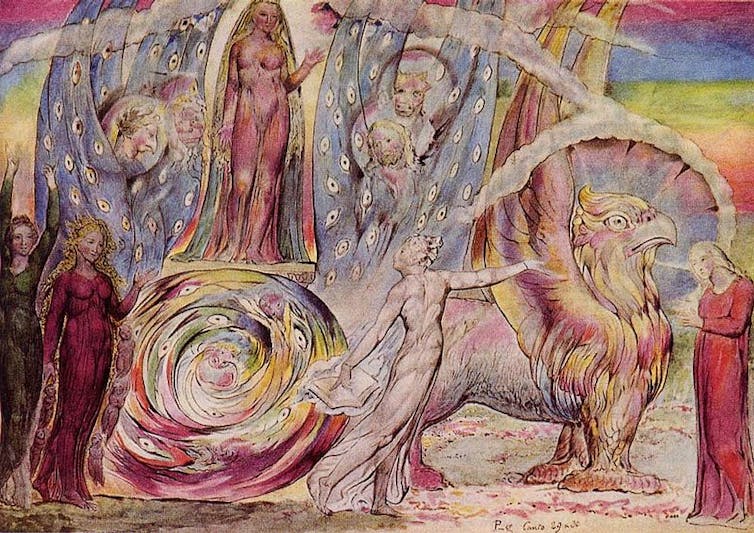

Blake achieved this with his religiously inspired poetic transformations of London. Blake imagines indentured child chimney sweeps set free by angels, even as he sees everywhere the “mind-forg’d manacles” of poverty and exploitation. Blake skewers the wretched present and envisages a transcendent future through poetic imagination.

Wikimedia Commons

The modern world can still be understood as swinging between, on one side, the cool work of quantification and observation in scientific rationality and, on the other, a desire for the heat of life lived with intensity, in the experience of emotion or of the ineffable. These latter qualities we find in imaginative and freedom-loving Romanticism, which made a home for itself in English poetry.

Poets such as Charlotte Smith, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Clare presented artistic critiques of what they saw as the exploitative and cold-hearted rationality of their times. These English poets found a refuge for their idea of free and creative humanity in nature and the imagination.

Blake achieved this with his religiously inspired poetic transformations of London. Blake imagines indentured child chimney sweeps set free by angels, even as he sees everywhere the “mind-forg’d manacles” of poverty and exploitation. Blake skewers the wretched present and envisages a transcendent future through poetic imagination.

Beatrice Addressing Dante by William Blake.

William Blake/Wikimedia Commons

Where Blake set out an idiosyncratic and radical religious revision, Wordsworth established a poetic interaction between imagination and nature in his landmark 1798 collection with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads. In his poem Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth outlines the idea of the sublime that would come to characterise the Romantic relationship between humanity and nature.

Wordsworth encounters nature but in it hears the “sad music of humanity”:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man

The Romantic sublime here casts nature as a stern teacher ready to impart wisdom if only humanity could be still and listen carefully. Edmund Burke went a little further with his theory of the sublime, in which the teacher is more like a crazed god who might overwhelm and annihilate us. Surviving the encounter, however, we are endowed with wonder and insight.

Beatrice Addressing Dante by William Blake.

William Blake/Wikimedia Commons

Where Blake set out an idiosyncratic and radical religious revision, Wordsworth established a poetic interaction between imagination and nature in his landmark 1798 collection with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads. In his poem Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth outlines the idea of the sublime that would come to characterise the Romantic relationship between humanity and nature.

Wordsworth encounters nature but in it hears the “sad music of humanity”:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man

The Romantic sublime here casts nature as a stern teacher ready to impart wisdom if only humanity could be still and listen carefully. Edmund Burke went a little further with his theory of the sublime, in which the teacher is more like a crazed god who might overwhelm and annihilate us. Surviving the encounter, however, we are endowed with wonder and insight.

The Romantic sublime in Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey casts nature as as a stern teacher ready to impart wisdom if only humanity could be still and listen carefully.

shutterstock

Wordsworth explained this control of the sublime experience in his poetic method. In his 1800 preface to Lyrical Ballads he describes the process of recreating the experience of nature and transforming it into poetry:

… poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origins from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.

Wordsworth argues that it takes a special kind of “mind” to recall the intensity of emotion that accompanies an encounter with a mountain or the roiling sea. As Shelley would reiterate later, the Romantic poet is cast as an almost priestly figure, mediating between humanity and nature through “his” capacious imagination.

The Romantic sublime in Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey casts nature as as a stern teacher ready to impart wisdom if only humanity could be still and listen carefully.

shutterstock

Wordsworth explained this control of the sublime experience in his poetic method. In his 1800 preface to Lyrical Ballads he describes the process of recreating the experience of nature and transforming it into poetry:

… poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origins from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.

Wordsworth argues that it takes a special kind of “mind” to recall the intensity of emotion that accompanies an encounter with a mountain or the roiling sea. As Shelley would reiterate later, the Romantic poet is cast as an almost priestly figure, mediating between humanity and nature through “his” capacious imagination.

An 1842 portrait of Wordsworth by Benjamin Robert Haydon.

Wikimedia Commons

But, of course, these “unacknowledged legislators” of human nature were not all men and not all so ready to present their special sensibilities. Charlotte Smith was an early Romantic poet who influenced Wordsworth. Smith’s melancholy nature poems present a less heroic vision of poetic imagination and the self. Her sonnet, To Night, includes a literary device that subsequent Romantic writers tended to neglect: irony.

Wordsworth and Shelley claim to access the transcendental voice of nature without conceding that they may, in fact, merely be hearing their own echo. Smith, on the other hand, acknowledges the vanity of communing with “the deaf cold elements”. It doesn’t stop her from anthropomorphising nature in its “sullen surges” and “viewless wind”. But she, at least, recognises the game she is playing.

Smith knows the human world is cruel and that nature can provide consolation, even when we admit it is actually indifferent to our suffering. In a way that Kant might not have anticipated, Smith presents a Romantic kind of enlightenment - a courage to use one’s own understanding of sorrow.

She addresses “Night” with some of the saddest and bravest lines in English poetry:

I still enjoy thee — cheerless as thou art;

For in thy quiet gloom the exhausted heart

Is calm, tho’ wretched; hopeless, yet resign’d.

This Romantic voice takes responsibility for itself by artfully imagining nature as a cool but consoling companion, rather than a distant sage or annihilating god. It is a knowing projection of our capacity for calm, set against a frantic and unjust world.

An 1842 portrait of Wordsworth by Benjamin Robert Haydon.

Wikimedia Commons

But, of course, these “unacknowledged legislators” of human nature were not all men and not all so ready to present their special sensibilities. Charlotte Smith was an early Romantic poet who influenced Wordsworth. Smith’s melancholy nature poems present a less heroic vision of poetic imagination and the self. Her sonnet, To Night, includes a literary device that subsequent Romantic writers tended to neglect: irony.

Wordsworth and Shelley claim to access the transcendental voice of nature without conceding that they may, in fact, merely be hearing their own echo. Smith, on the other hand, acknowledges the vanity of communing with “the deaf cold elements”. It doesn’t stop her from anthropomorphising nature in its “sullen surges” and “viewless wind”. But she, at least, recognises the game she is playing.

Smith knows the human world is cruel and that nature can provide consolation, even when we admit it is actually indifferent to our suffering. In a way that Kant might not have anticipated, Smith presents a Romantic kind of enlightenment - a courage to use one’s own understanding of sorrow.

She addresses “Night” with some of the saddest and bravest lines in English poetry:

I still enjoy thee — cheerless as thou art;

For in thy quiet gloom the exhausted heart

Is calm, tho’ wretched; hopeless, yet resign’d.

This Romantic voice takes responsibility for itself by artfully imagining nature as a cool but consoling companion, rather than a distant sage or annihilating god. It is a knowing projection of our capacity for calm, set against a frantic and unjust world.

Authors: Matthew Ryan, Lecturer in Literature, Australian Catholic University