Rossini’s William Tell, and its famous overture

- Written by Madeline Roycroft, PhD candidate and tutor in music history, University of Melbourne

Although it boasts one of the most famous sequences of music in existence, Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell is hardly a staple of the operatic repertoire. At five hours long in its original composition, and with a challengingly high male singing part, it is rarely heard in its entirety. Victorian Opera’s current production of William Tell, a three-hour abridged version, is the first in Australia in over 140 years.

The opera is certainly most famous for its 12-minute Overture, the piece that sets the scene for it. Few excerpts of classical music have been used (and indeed, parodied) in popular media as frequently. Now widely recognised as the theme to The Lone Ranger, the tune also appeared in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange (in an electronic arrangement by American composer Wendy Carlos). Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny and The Flintstones can all be credited for the Overture’s presence in popular cartoons.

The Flintstones take on Rossini’s William Tell Overture.The work premiered at the Paris Opéra in 1829, not long after Rossini settled in France following successful tours of Vienna, Bologna, Venice and London. Yet, after only three performances, sections of the score were already being cut for the comfort of the audience.

Rossini in 1829.

Wikimedia

Rossini in 1829.

Wikimedia

In 1830, the Vienna Court Opera staged their 1830 German-language version over two consecutive evenings. Accommodations like these inspired Rossini to prepare an “official” abridgement in 1831, but it was too late: a myriad of translations, adaptations and truncations had already appeared. Consequently, there are many versions of William Tell for present-day opera companies to consider.

A ‘grand’ opera

William Tell was the first serious opera the Italian-born Rossini authored in Paris. Upon granting his residency in 1824, the French government contracted him to produce a work for the Paris Opéra: an institution that demanded grandiose music with noble storylines, often based on heroic historical events. These productions were sung-through (dialogue detracted from the “seriousness” of the music), and the stage designs, effects and costumes were all suitably lavish. Throughout the 1830s, this style became known as “grand opera”.

As the composer responsible for the Italian opera craze that had swept Paris in earlier decades, it is no surprise that Rossini rose to the challenges of this elite new genre. For what would become a masterwork of the 19th century, Rossini borrowed the plot of a German play: Friedrich Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell (1804).

Appropriately grand in subject matter, the storyline follows the legendary Swiss marksman who inspired rebellion in 14th-century, Austrian-occupied Switzerland. The popularity of William Tell gave way to a golden age of Parisian grand opera.

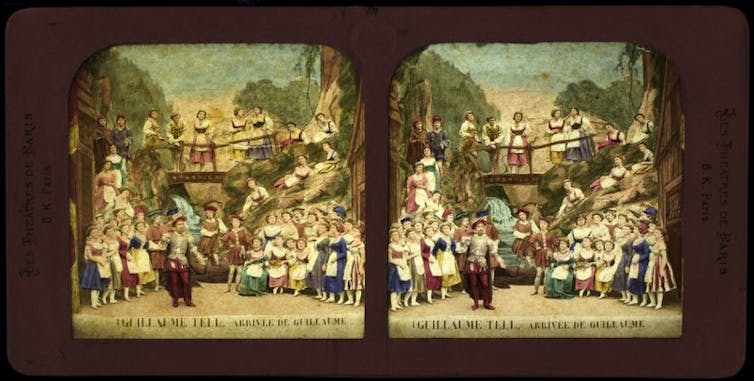

An 1860s French staging of William Tell.

Wikimedia

An 1860s French staging of William Tell.

Wikimedia

Read more: How Beethoven's 'mistake' became one of our most famous tunes

In addition to its use of fable, William Tell explores themes of paternal relations, and the conflicts of an occupied nation seeking independence and peace.

Tired of Switzerland’s continued oppression, the plot sees William Tell convince a young Austrian soldier, Arnold, to assist in a rebellion. Yet, Tell is arrested when he and his son Jemmy do not pay their respects on the hundredth anniversary of Austrian rule.

The Austrian governor Gesler orders Tell to shoot an apple off Jemmy’s head: if he refuses, both of them will die. In the poignant solo “Sois immobile” (“Be motionless”), Tell urges Jemmy to stand completely still and think of his mother. Despite being a male character, Rossini intended Jemmy to be performed by the higher-pitched voice of a female soprano, in line with the bizarre operatic tradition known as the “trouser role”.

Although Tell successfully shoots the apple, Gesler only releases Jemmy. Upon learning of Tell’s imprisonment, Arnold becomes set on revenge, and with a rousing call “Amis, amis, secondez ma vengeance” (“Friends, friends, second my revenge”), he inspires a group of Swiss confederates to storm the capital. The repeated and sustained high notes make this one of the most demanding tenor arias in the repertoire.

An iconic overture

The overture’s popularity in isolation from the larger work began with Austrian composer Johann Strauss Snr’s Wilhelm Tell Galop (premiered in 1829, mere months after the original opera). Hungarian composer Franz Liszt’s 1838 transcription for solo piano also contributed to the appeal; it was standard practice in the 1830s for touring pianists to show off with virtuosic arrangements of opera highlights, and William Tell was at the core of Liszt’s repertoire.

While the Finale is undoubtedly the most recognisable, the Overture is actually structured in four contrasting sections. It tells a story within itself, making it structurally distinct from anything Rossini had composed before.

Representing daybreak and functioning as a prelude to the upcoming three parts, the Overture opens with a gentle passage in the lower strings. A solo cello presents the melody, which then enters into dialogue with the remaining players in the section.

Double basses gradually thicken the texture; meanwhile, two distant timpani rolls hint at an incoming storm. For the French composer Hector Berlioz, the prelude evoked “the calm of profound solitude, the solemn silence of nature when the elements and human passions are at rest.”

The upper strings (violins and violas) announce the transition to the Overture’s energetic second phase. Shimmering string phrases are punctuated by short interjections from the woodwinds, which build in intensity until dynamic brass and percussion announces the arrival of the storm. As the chaos subsides, sections of the orchestra fade away until only a solo flute remains.

In the pastoral third movement, we meditate upon the plaintive tone of the cor anglais (a larger member of the oboe family). Rossini turns a ranz des vaches (a traditional Swiss herdsman’s melody) into a duet between cor anglais and flute, in what is now one of the most renowned orchestral woodwind solos.

Suddenly, the peaceful scene is interrupted by a fast-paced, high-intensity galop, which was a popular style of ballroom dance at the time. Titled “The March of the Swiss Soldiers”, it points toward the majestic final scenes of the opera, where the Swiss Armed Forces free their homeland from Austrian rule. (For the full impact of the abrupt transition, it’s best to listen to these two sections in sequence.)

Despite living for another 40 years, William Tell was last opera Rossini would compose. In stark contrast to today’s circumstances, the financial viability of William Tell was such that Rossini was able to enter semi-retirement, composing only cantatas, sacred and secular vocal music until his death in 1868.

William Tell is being staged by Victorian Opera until July 19.

Authors: Madeline Roycroft, PhD candidate and tutor in music history, University of Melbourne