will the universe expand forever, or contract in a big crunch?

- Written by Tamara Davis, Professor, The University of Queensland

This is an article from Curious Kids, a series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky!

What’s more likely - that the universe will expand forever, or that it will contract in a big crunch, causing the end of the cosmos? – Mushahid, aged 16, Chitral, Pakistan.

About a century ago, we didn’t even know that galaxies existed.

Then, in the 1910s, astronomers figured out how to measure the distance to features called “spiral nebulae” they were seeing in the sky. Although these looked like clouds of gas nearby to us, the scientists realised they were whole galaxies containing billions of stars, really far away.

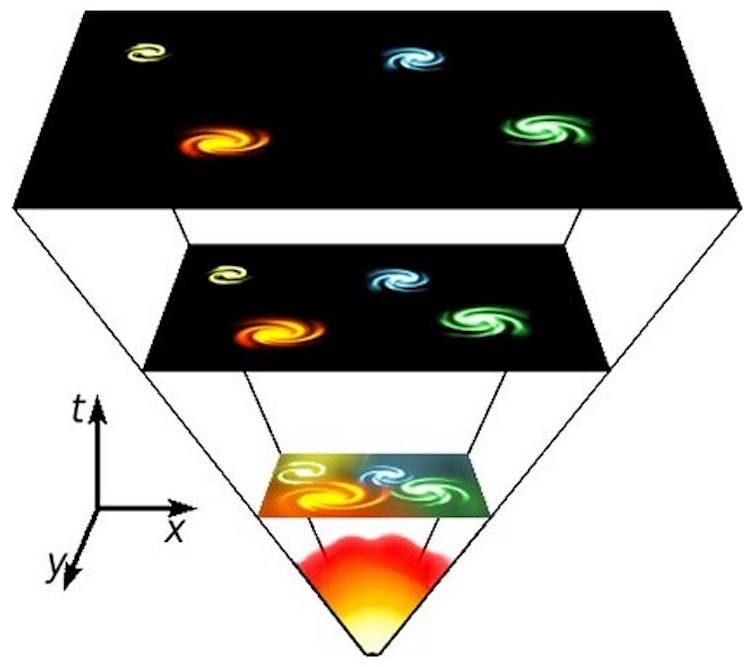

Pretty much as soon as we understood what galaxies were, we discovered that they are all moving away from each other, and the ones that are further away are moving faster — in other words, the universe is expanding.

The expansion of the universe is everywhere - all points are moving away from each other.Ever since then the question has been: will the universe expand forever, or will it one day recollapse in a “big crunch”?

Read more: Curious Kids: Does space go on forever?

There’s a reason this was a puzzle: it’s because gravity should be slowing down the expansion. All the galaxies pull on each other in the same way that the earth pulls on us and brings us back down when we jump.

When I throw a ball up into the air, initially it may be going fast, but then it slows down, stops going up, and falls back to Earth.

However, if I throw it fast enough so it’s travelling at more than 11 kilometres per second (that’s very fast!), then it will never come back to Earth. It will have what’s called the “escape velocity” – this is the speed at which Earth’s gravity will not be strong enough to pull it back down.

If I was on the Moon, it gets even easier because the mass of the Moon is smaller: its almost 100 times lighter than Earth. That means the force due to gravity there is less, and therefore I could throw the ball much more slowly and it would still escape the moon’s gravity. Just over 2 kilometres per second would do it.

So the question becomes: how heavy are all the galaxies, and are they moving fast enough away from each other to have the escape velocity? If so, the universe would expand forever.

After the Big Bang (shown at bottom), everything expanded away from everything else.

physicsoftheuniverse.com

After the Big Bang (shown at bottom), everything expanded away from everything else.

physicsoftheuniverse.com

We had to wait until the 1990s when measurements became precise enough to figure out the answer. And the answer came as a big surprise. When astronomers finally measured how the expansion was changing, they discovered that gravity wasn’t actually slowing it down at all. In fact, the expansion was speeding up!

That’s sort of crazy, because it means that gravity is working in reverse: something is pushing the galaxies away from each other. It is as strange as if I threw a ball gently up in the air and watched it accelerate off into space.

We don’t know what is causing the acceleration, but we give it the name dark energy.

Read more: Curious Kids: Why do you have to wear a helmet in space?

Even though we don’t actually know what dark energy is, we can now answer the original question — yes, the universe will expand forever and we’ll experience a “big freeze”, not a “big crunch”.

The galaxies will all keep getting further apart from each other, the universe will get colder and colder, and eventually any galaxies beyond our local group will become so faint and distant that we won’t be able to see them at all — their light won’t even be able to reach us.

There’s even a chance that the acceleration might get so extreme that it rips apart our own galaxy, and eventually even rips apart atoms… destroying us all. That would be called the “big rip”. Most likely, though, we’re headed for a big freeze.

So the universe is going to last a very long time, but the future will be cold and dark.

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. They can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au * Tell us on Twitter

CC BY-ND

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.

CC BY-ND

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.

Authors: Tamara Davis, Professor, The University of Queensland