the Horne family study gets a second life

- Written by Julia Horne, University Historian and Principal Research Fellow, History, University of Sydney

The Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room will open today in a gracious space in the State Library of New South Wales. One side of it is adorned with objects from the home where I lived with my family, my father Donald Horne (1921-2005), author of The Lucky Country and numerous other books, and my mother, journalist and editor Myfanwy Horne (1933-2013) who wrote as Myfanwy Gollan.

The rest of the room is set aside for study based on ideals of scholarly curiosity, imaginative inquiry and intellectual creativity. As my father wrote shortly before he died, words like curiosity and imagination help “celebrate scholarship and the marvels of the intellectual life more generally”.

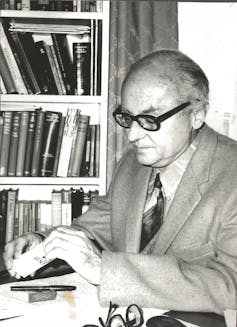

Donald Horne at his desk in 1969.

Author provided

Donald Horne at his desk in 1969.

Author provided

The State Library has selected certain objects from my family home to inspire their scholars and fellows program — an upholstered mid-20th century armchair, a large 19th century pedestal desk and a collection of some 4000 books.

The armchair, now upholstered in a dark green material over the original knobbly grey fabric, was acquired by my parents to furnish their first home in 1960, a small, rented two-bedroom garden flat in Sydney’s leafy Double Bay.

It was on this chair, in 1964, that my father sat “pen in hand, pad on knee”, as my mother later wrote, “to write The Lucky Country”. I was too young to remember this act of defiance, as some now see it — after all, surely a serious writer sits at a desk. The act itself was born out of necessity, and only later became symbolic (at least in my parents’ minds) when my father acquired a new string to his professional bow — a writer of books.

Read more: Donald Horne's 'lucky country' and the decline of the public intellectual

In the early years of their marriage in their small flat, my parents had a choice: to turn a spare room into a dining room or into a study with a desk. A dining room it became, and instead of a desk, they purchased a mahogany dining table. Not only does this choice show the importance of the dining room in middle class Australia, but also the consequence my parents gave to the well-planned dinner party. My father even brought to his marriage several signature dishes, including a delectable petit pois dish I still cook to this day as well as Ted Moloney’s and George Molnar’s Cooking for Bachelors (1959).

The Lucky Country came out of formal quests for knowledge, but also arose out of congenially robust discussion around the dining room table. My mother acquired a new professional role, as editor of all her husband’s books and much of his other published writing. The armchair, then, marks a state of transformation in my parents’ working and personal lives and in their home, as an enduring workshop of ideas.

Myfanwy Horne at her desk in the study, 1973.

Author provided.

Myfanwy Horne at her desk in the study, 1973.

Author provided.

In 1966, we moved from our rented flat to our new house, a late 19th century two-storey terrace with room for both a dining room and a study. It remained my parents’ home for the rest of their lives and was not sold until 2015. The spacious, high-ceiling upstairs room at the front was soon furnished as a writers’ study.

Book cases graced either side of the fireplace, one with a small built-in desk for my mother to work at on her typewriter. The French doors leading on to the front verandah were shaded by heavy, satin, mustard coloured curtains. The centrepiece was the large, 19th century pedestal desk chosen by my mother. Placed in the middle of the room at a slightly raffish angle, my father savoured the room as a place to write, surrounded by bookcase-lined walls.

As he later wrote, “sitting at the desk Myfanwy had chosen for me became one of our essential ceremonies” of intellectual life together. “My writing came from a joint workshop of which she was a part. Not only the dinners and lunch parties that helped keep things going: without her emotional support and intellectual support I don’t know that I would have ‘become a writer’.”

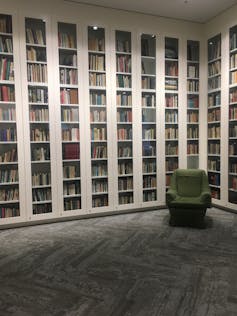

Books and the green armchair in the Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room.

Photo courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Books and the green armchair in the Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room.

Photo courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Books that influenced my father’s writing and thinking are now displayed in beautiful glass cabinetry in the State Library. You can peruse the spines for a quick trip through 20th century ideas, global politics and history, its revolutions, art, political philosophy, sociology. Well-thumbed copies include A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by the 18th century advocate of women’s rights, Mary Wollstonecraft, and The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies by the 20th century cultural theorist, Roland Barthes, for its critique of bourgeois culture.

Many of the books include his annotations — paper clips, discrete dots, vertical lines and squiggles — making it possible to trace some of what inspired his own social and political critique. The English translations of the writings of the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, for instance, were marked up for his favourite passages on hegemony, “common sense” and the idea that we are all intellectuals. They represent, in many ways, his scholarly footnotes.

“I’ll just go to the study to look it up,” is a refrain I often heard from my parents. Rather than reconstruct their study, the artefacts in the State Library’s Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room have been chosen to continue the intellectual pursuit of conversation and ideas.

You can work at the desk, sit in the green armchair and — by application to the librarian — peruse the books and decipher the scrawls left by my father. These objects are not only tokens of two productive writing lives, but an inspiration to future generations who believe that books and ideas matter.

Authors: Julia Horne, University Historian and Principal Research Fellow, History, University of Sydney