Australia imports almost all of its oil, and there are pitfalls all over the globe

- Written by Anthony Richardson, Research Fellow, Future Social Service Institute, RMIT University

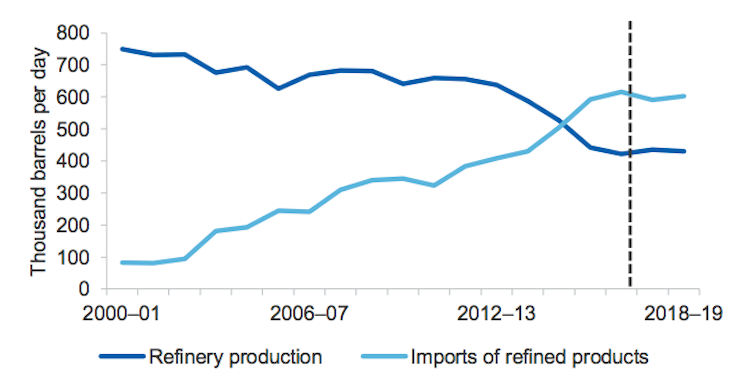

Australia’s fuel security is far more precarious than we might realise. Not only do we not have the internationally mandated 90-day stockpile, but the ongoing closure of Australia’s refineries means we are on track to be 100% reliant on imported petroleum by 2030.

Read more: Australia's fuel stockpile is perilously low, and it may be too late for a refill

Australian refineries import roughly 83% of the crude oil they process from more than 17 countries, mainly in Asia (40%), but also Africa (18%) and the Middle East (17%). We are a significant oil producer, but export 75% of our crude production, with the largest recipients being Indonesia and Singapore.

At the same time, the importance of importing refined petroleum from overseas is only increasing as our local production declines.

Australia’s imports and production of refinery products.

Dept Environment and Energy/Dept Industry, Innovation and Science

Australia’s imports and production of refinery products.

Dept Environment and Energy/Dept Industry, Innovation and Science

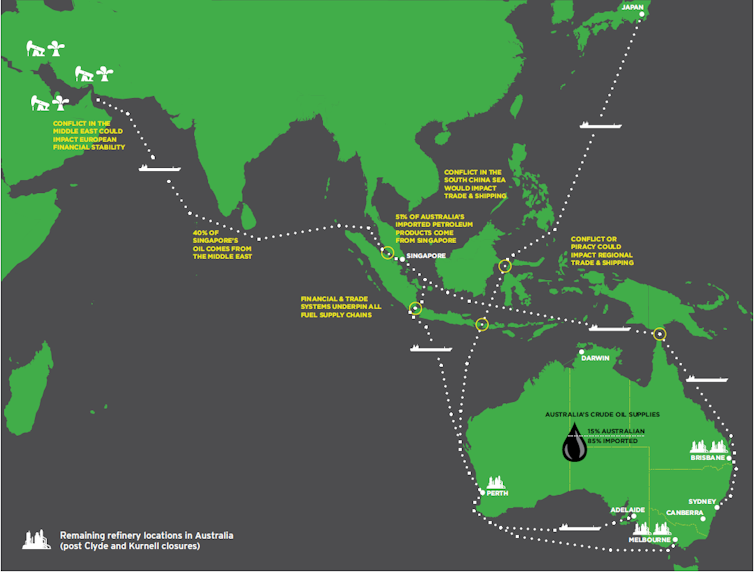

Currently, 51-53% of our imported refined petrol comes from Singapore’s refineries, with 18% from South Korea, 12% from Japan and the rest from a range of other countries. Asian refineries in particular are extremely competitive in terms of production and transport costs.

Australia’s fuel supply routes.

NRMA

Australia’s fuel supply routes.

NRMA

The consequences of disruption

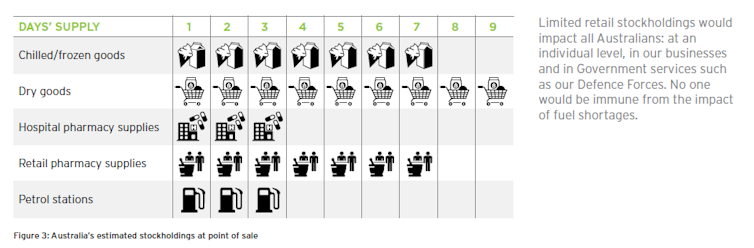

Without significant fuel reserves, Australia could face serious consequences in the event of disruption to these imports. In any complex system, even temporary disruptions can cause “cascading failures” across other parts of the system, and these effects don’t stop the moment the supply is restored.

Maintaining our oil supply is not just about keeping our cars on the road. Any serious disruption would have consequences within days for our food supplies, medication stocks, and military capacity.

Australia’s liquid fuel reserves compare poorly with stockpiles of other goods.

NRMA

Australia’s liquid fuel reserves compare poorly with stockpiles of other goods.

NRMA

If a complex system is to be resilient, it needs redundancy. This means that it has backup processes that enable the overall system to continue to function even when some part of it breaks down.

Unfortunately, such backup systems are not efficient, because the system is doubling up on resources. Efficiency is therefore one of the enemies of system resilience – this is best demonstrated by the concept of “just in time” supply chains, in which stock arrives when it is needed, minimising the costs of holding excess inventory in stock. Such an approach is certainly efficient, but it is also fragile. This is a pretty good description of Australia’s current oil supply chains.

The 90-day oil reserve recommended by the International Energy Agency is a textbook example of system redundancy, as are local oil refineries. They provide onsite reserves (5-12 days) and local refining capacity. But in the interests of economic efficiency we have chosen not to invest in this redundancy.

Possible causes of disruption

Australia’s geographically dispersed oil supply chains mean that there are several places around the world where they can potentially be disrupted.

More than 40% of the world’s oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz, the only sea passage out of the Persian Gulf. Controlling the strait remains a clear (and possibly achievable) aim of Iran in any military confrontation.

This has arguably been made more likely by the US administration’s decision to reimpose economic sanctions on Iran. At the same time, the recent shale gas revolution in the United States has weakened the traditional US strategic imperative to keep the strait open.

The ongoing tensions in the South China Sea also threaten Australia’s other major supply route for oil, not least because of our difficult geopolitical position in the middle of the heavyweight rivalry between the US and China.

Finally, the apparent defeat of the Islamic State group in Iraq and Syria has led to concerns that radicalised Indonesians are returning home to continue the fight. The vulnerability of our supply lines through Indonesia has already been recognised.

Trading places

Oil is often described as a “fungible commodity”. This means that oil from different suppliers is interchangeable, so if supply is disrupted we can just buy it from somewhere else.

But it is not as straightforward as that. First, the point in the system at which supply is disrupted is crucially important. For example, Australia’s fuel ports represent particularly problematic junctions, as a 2013 fuel security review for the National Roads and Motorists Association pointed out:

For example, the primary fuel port in South Australia is at Port Adelaide; a single, narrow, shipping channel services the port. A blockage of that channel, as the result of a shipping accident/incident, could result in significant and prolonged disruption to fuel supplies for Adelaide and a large part of the state … given the inability to transport sufficient fuel stocks overland to South Australia.

What’s more, while it is generally true that oil is fungible within an open global market, not all suppliers necessarily share this assumption. Thus China, faced with rising domestic consumption, is planning to outbid Western oil companies for contracts, or else buy the entire companies outright.

Just like the US, China sees oil more as a national security concern than as a fungible global commodity. Access to even a share of the global oil supply can be a tool of political or economic influence, as the OPEC embargo in the 1970s infamously showed.

Read more: Four decades later, has America finally got over the oil crisis?

In the end, while other countries move to secure their national fuel supplies, we continue in our misguided faith in an unfettered global oil market being able (or willing) to supply our needs in situations of crisis. Hopefully the proposed Fuel Security review will mean these challenges are finally taken seriously.

Authors: Anthony Richardson, Research Fellow, Future Social Service Institute, RMIT University