The new 100% recyclable packaging target is no use if our waste isn't actually recycled

- Written by Atiq Zaman, Lecturer, Curtin University

Commonwealth, state and territory environment ministers last week agreed on an ambitious target that 100% of Australian packaging be recyclable, compostable or reusable by 2025. This is no doubt sensible, given the turmoil sparked by China’s crackdown on waste imports.

Having a 100% target is fantastic. But this does not mean that all of the waste we generate in 2025 will necessarily find its way to one of these destinations.

For one thing, the definitions of different waste categories vary by state and territory, so there is no commonly accepted working definition of what constitutes “recyclable, compostable or reusable”.

Read more: China's recycling 'ban' throws Australia into a very messy waste crisis

In practice, these terms depend largely on the infrastructure available. Single-use plastic bags are a good example of a product that is technically recyclable but which is not accepted in most councils’ kerbside recycling collection. That’s because they are often contaminated with food waste and many councils lack the machinery to process them.

On its own, the new 100% target is not enough, because it doesn’t guarantee that recyclable or reusable items will definitely be recycled or reused. To really make a difference, we also need policies and market incentives to ensure that these things end up where we want them to.

Driving recycling

We can see this principle in action by looking at the issue of drink containers. Glass and plastic bottles are already 100% recyclable, yet there is a stark difference in recycling rates between states that do have container deposit schemes, and those that don’t.

In South Australia, which has had container deposit legislation for more than 40 years, almost 80% of drink bottles are recycled. But in Western Australia, where similar legislation is only at the discussion stage, the rate is just 65%.

Despite the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ attempt at a National Waste Account in 2013, little nationwide data are available, thanks to a lack of a consistent reporting framework across different jurisdictions.

Plastic not fantastic

In sectors where not all waste is fully recyclable, the problem is more complex still. Of the seven categories of plastic packaging, only three are economically viable to recycle: PET (soft drink bottles); HDPE (milk bottles); and PVC (shampoo bottles). The other four – LDPE (garbage bags); PP (microwaveable cookware); PS (foam hot drink cups); and other plastics – are less economically viable and so are recycled at much lower rates. While these plastics will still be allowed under the new target as they are technically recyclable, the new target might prompt a switch to less problematic materials.

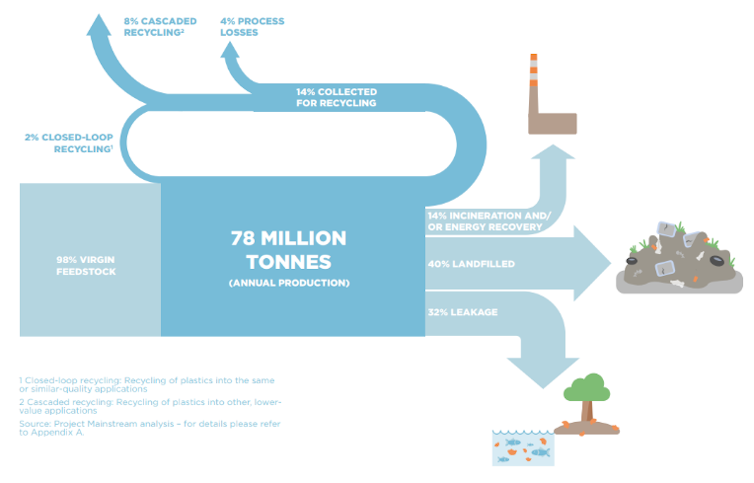

Globally, around 78 million tonnes of plastic is used every year, but only 14% is collected for recycling, while 14% is incinerated and the remaining 72% ends up in landfill or as litter in the environment.

The fate of the world’s plastics.

Author provided

The fate of the world’s plastics.

Author provided

The problems are no less vexing for other types of waste. With market rates for many types of recyclable paper having dropped to zero in the wake of China’s import restrictions, it will be hard to see how some products will be recycled at all, if left purely to economic forces.

Retailers may have to embrace more innovative solutions to improve the quality of recycling waste, such as reverse vending machines, which accept items such as aluminium cans and plastic or glass bottles – as long as they are cleaned and sorted. However, without creating a local waste market or government incentives, we cannot expect retailers to buy their packaging back.

And this is before we even consider the complexities of composting and reuse. Compostable waste as a whole is already facing problems due to a high contamination rate, and lack of separate bin for recycling organic waste in many local councils. Reuse, meanwhile, needs us to tackle the eternal problem of people’s perceptions and behaviour about using old packaging again.

Will some kinds of packaging disappear?

Under the product stewardship initiative, which calls on producers and retailers to take care of the waste produced after consumption of goods, it seems more likely that some materials will simply be phased out of the product supply chain altogether.

The impending plastic bag bans in several states and leading supermarkets offers a chance to replace them not with heavier, more durable plastic, but with biodegradable, renewable and eco-friendly natural materials such as hemp.

In turn, this would boost hemp production (alongside the legalisation of hemp-based medicine and food products in Australia). This could lead to the opportunity for manufacturing industry to produce environmentally friendly biodegradable plastics. Hemp-based biodegradable plastic would significantly safeguard the environment, even if we failed to achieve a 100% recycling of biodegradable plastic packaging. Similarly, glass or aluminium might be used instead of plastic, and are more easily recycled.

Even more innovatively, we might even see the arrival of edible packaging derived from the milk protein casein, formed into film rather like plastic cling wrap, which can be used to package foods such as butter or cheese.

Read more: The recycling crisis in Australia: easy solutions to a hard problem

We need a better target

We’ve established that it’s not enough simply to set a target of making 100% of our waste recyclable, compostable or reusable. To really feel the benefits we need a follow-on target, such as actually recycling 100% of our packaging by 2030.

For this to work, we would need three things:

- legislation, regulations or incentives for manufacturers to develop new packaging types;

- an increase in public participation rates in recycling; and

- the development of a strong domestic market for recyclable materials.

Finally, we should remember that waste prevention is better than waste management. Everyone – from governments, to manufacturers, to retailers, to consumers – should focus first on generating less waste in the first place. Then the fiendish problem of what to do with our waste will be all the smaller.

Authors: Atiq Zaman, Lecturer, Curtin University