Why the Commonwealth should resist meddling in schools

- Written by Julie Sonnemann, Research Fellow, Grattan Institute

Australia’s education debate is shifting at last, from how much money governments should spend on schools to how best to spend the money for the benefit of students.

After winning parliamentary approval for the Gonski 2.0 schools funding deal (the “how much”), the Turnbull Government has commissioned the “Gonski 2.0 Review” to advise on how to spend the money wisely (the “how best”).

David Gonski, the chair of the Gonski education funding reviews.

AAP/Joel Carrett

David Gonski, the chair of the Gonski education funding reviews.

AAP/Joel Carrett

But the extra Commonwealth money going to schools (A$23 billion over the next 10 years compared to previous Coalition policy) is only 3% of all government spending on schools over the decade. It should not be used as an excuse for the Commonwealth to intervene more heavily in school education policy.

The Grattan Institute’s new report, The Commonwealth’s role in improving schools, examines what the Commonwealth should do if it really wants to boost student outcomes.

And the answer is: not very much.

Read more: The passage of Gonski 2.0 is a victory for children over politics

States are better placed to drive reforms

The states run schools, as well as providing most of the funding. Heavy-handed Commonwealth intervention is likely to be counterproductive, costly and confusing.

Most of the big reforms needed are within the responsibilities of state governments. For example, all the evidence shows effective teaching has the largest impact on student achievement. The biggest advances will be made when teachers know what works in the classroom, and how they can adapt their methods to better target their teaching to the particular needs of their students.

For this to happen, teachers need better support from the “system”: for example, better teacher development and greater standardisation of classroom materials so individual teachers don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

In school education, the states and territories are the “system” managers. Driving reforms such as these from Canberra would be difficult.

Federal funding conditions aren’t the way to go

Australia must learn from its history. Our report shows imposing prescriptive funding conditions on states and territories has been tried before, with little benefit.

Commonwealth interference can destroy policy coherence and simply increase red tape. The Commonwealth has few ways to independently verify if change is actually happening in the classroom, so adding an extra layer of government policies that chop and change only disrupts schools and teachers.

For example, the 2008-2013 National Partnership agreements for school education included a number of prescriptive and input-based conditions. These increased the administrative and compliance burden of states, and created instability in schools when the funding and initiatives stopped abruptly five years later.

Before looking to new reforms, the Commonwealth government should first deliver its existing responsibilities more effectively. These include initial teacher training, the national curriculum and national student testing. All require constant attention, and some require urgent reform.

Read more: Changes to school funding – your questions answered

Prioritise a few national reforms only

If determined to act, we suggest the Commonwealth focus strategically on a small number of national reforms only. It is far better to focus on a few actions with a high chance of success.

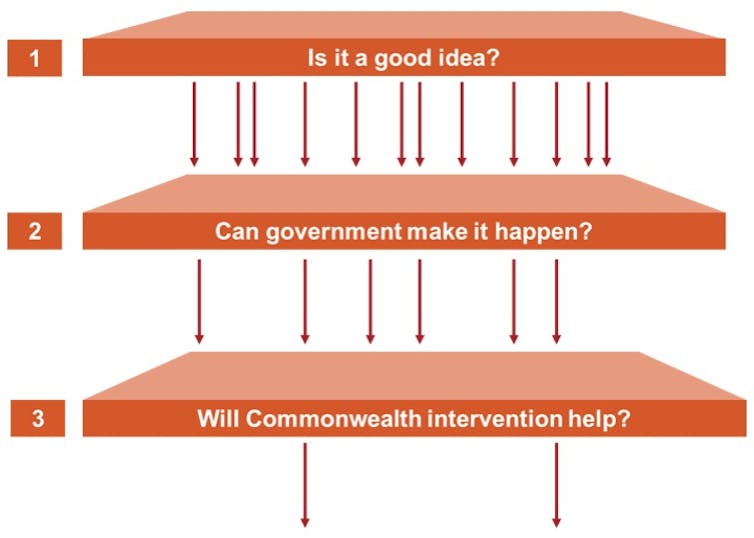

We suggest the Commonwealth only pursue reforms that meet all of three criteria: the evidence shows it’s a good idea, the government can make it happen, and Commonwealth intervention will help. While many Commonwealth ideas are good in theory, many fall down on whether they can be readily implemented by state governments and actually lead to change in practice.

For example, in 2016 the Commonwealth signalled an intention to require all schools to use explicit teaching. While backed by evidence, this type of Commonwealth policy requirement is unlikely to lead to change without a raft of complementary state government policies. These include the right training and school support for teachers to switch to explicit teaching. It would be difficult for the Commonwealth to independently verify, and it also creates confusion by coming in over the top of state policies on effective teaching methods.

Commonwealth intervention must satisfy three criteria

Author provided/Grattan Institute

Four suggestions for new national reforms

We have four suggestions for new national reform areas where there are benefits of scale and coordination. These only to be pursued if state government’s have strong “buy in” and there is close collaboration in design and delivery:

1. Create a new national school education research organisation to investigate what works to drive school improvement and to spread the word across schools, states and sectors. The new body should be charged with lifting the standard of education research in Australia, establishing a long-term research agenda for school education, and promoting key findings across the country. It could link up all research on education for people from birth through to age 18, so policy makers and the community better understand the continuum of learning, from early childhood to school and vocational education.

2. Invest more in measuring new, non-cognitive skills such as teamwork and resilience, in the classroom. At present, Australia focuses much more on old, foundational skills such as literacy and numeracy, which are only one element of what we expect from 21st century schooling.

3. Develop better ways to measure student progress, for national bench-marking and for use in the classroom. NAPLAN seeks to measure students’ learning progress in core literacy and numeracy skills at the national level, but NAPLAN gain scores are not easy to interpret when comparing the progress of different student groups.

4. Invest in high-quality digital assessment tools for the classroom, so teachers know what their students know and how much progress their students have made.

Read more:

Gaps in education data: there are many questions for which we don't have accurate answers

Resist over-reach

The extra Commonwealth money for schools under Gonski 2.0 is welcome. The shift in the education debate towards how best to use the extra money is still more welcome.

But for Australian students to get the most benefit, the Commonwealth must resist the temptation to over-reach by intervening heavily in school education policy.

Author provided/Grattan Institute

Four suggestions for new national reforms

We have four suggestions for new national reform areas where there are benefits of scale and coordination. These only to be pursued if state government’s have strong “buy in” and there is close collaboration in design and delivery:

1. Create a new national school education research organisation to investigate what works to drive school improvement and to spread the word across schools, states and sectors. The new body should be charged with lifting the standard of education research in Australia, establishing a long-term research agenda for school education, and promoting key findings across the country. It could link up all research on education for people from birth through to age 18, so policy makers and the community better understand the continuum of learning, from early childhood to school and vocational education.

2. Invest more in measuring new, non-cognitive skills such as teamwork and resilience, in the classroom. At present, Australia focuses much more on old, foundational skills such as literacy and numeracy, which are only one element of what we expect from 21st century schooling.

3. Develop better ways to measure student progress, for national bench-marking and for use in the classroom. NAPLAN seeks to measure students’ learning progress in core literacy and numeracy skills at the national level, but NAPLAN gain scores are not easy to interpret when comparing the progress of different student groups.

4. Invest in high-quality digital assessment tools for the classroom, so teachers know what their students know and how much progress their students have made.

Read more:

Gaps in education data: there are many questions for which we don't have accurate answers

Resist over-reach

The extra Commonwealth money for schools under Gonski 2.0 is welcome. The shift in the education debate towards how best to use the extra money is still more welcome.

But for Australian students to get the most benefit, the Commonwealth must resist the temptation to over-reach by intervening heavily in school education policy.

Authors: Julie Sonnemann, Research Fellow, Grattan Institute

Read more http://theconversation.com/why-the-commonwealth-should-resist-meddling-in-schools-91623