How we're developing underground mapping technologies - lessons from the Beaumont case

- Written by Ian Moffat, ARC DECRA Research Fellow in Archaeological Science, Flinders University

It’s difficult to look on the bright side when children missing for 52 years still aren’t found.

However my recent work with the South Australian police in identifying a potential burial site of Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont (not seen since Australia Day 1966) has advanced a method for identifying disturbed soil, archaeological material and unmarked grave sites.

Known as electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), this technique maps underground features in 3D.

This recent survey took place on the grounds of the New Castalloy factory in South Australia. The land became a renewed site of interest in the Beaumont case when two new witnesses came forward and said that they had dug, as teenagers, a large hole at the site on the same weekend as the Beaumont children disappeared.

Unfortunately, following excavation on the site, we now know the new area of focus contained nothing but animal bones and other debris. While this was not the result that was hoped for, ERT was critical in narrowing down a large block of land to find a smaller zone that was feasible for excavation. Without this technology it is likely that police investigation would have been unable to proceed and that this area of the Castalloy site could not have been ruled out as being of interest.

How does geophysics find graves?

My background is in geology and geophysics, but my research for the past fifteen years has focused on archaeological targets and, in particular, the location of unmarked graves.

Unfortunately, the techniques we use don’t work as “bone detectors” directly: instead, they map soil disturbance caused by the mixing and repacking of soil layers during the back filling of graves. Obviously finding disturbance alone is not enough to identify a grave, it needs to have appropriate dimensions and should reflect historical information or witness statements about the site.

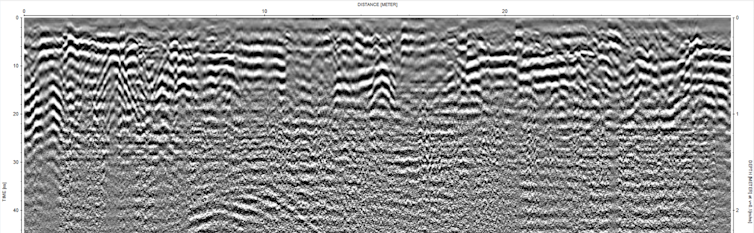

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is a forensic approach commonly used to explore underground features, which sends pulses of radar energy into the ground and measures the response. This creates 2D profiles which show the soil structure and composition, in an image which is something like digging a trench and looking at the wall.

However GPR was not suited to investigate the New Castalloy site - mainly due to the depth of the potential burials (up to four metres below ground level). The radar signal rapidly decreases with depth for GPR surveys in areas with electrically conductive soils, such as the shallow areas of this site. I did trial GPR at the New Castalloy factory however the results show nothing below around 1m depth.

GPR profile from the New Castalloy site.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

GPR profile from the New Castalloy site.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

On that basis, I decided to use Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT). To my knowledge, this was the first time this technique has been applied to a forensic case in Australia.

However, an ERT survey takes time. My team and I worked for 14 hours a day for three consecutive days to image the site. This time requirement may explain why ERT, while widely used in the mineral exploration industry, has not been extensively used in forensic investigations in Australia before.

ERT works by injecting electricity into the ground and then measuring how well (or poorly) it travels to a series of receiving electrodes. The electrodes are connected to the ground with metal pegs that are watered to ensure the current can travel easily into the ground.

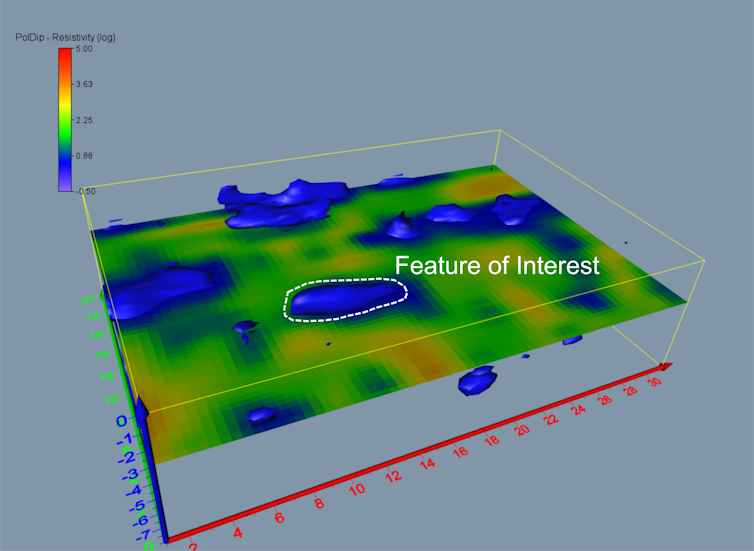

On the New Castalloy site I was able to image to a maximum depth of 10m, with a resolution along the lines of 0.5m.

3D ERT Data from the New Castalloy site with the feature of interest shown in white.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

3D ERT Data from the New Castalloy site with the feature of interest shown in white.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

What we found

The ERT data was processed into a series of 2D profiles, depth slices and a 3D cube with the assistance of Kleanthis Simyrdanis, an expert in the archaeological use of ERT, from the Institute for Mediterranean Studies in Crete.

Read more: Pilot study on why academics should engage with others in the community

I reviewed this data to look for areas of soil disturbance with dimensions and a location that reflected witness accounts of a potential grave site. Two connected features immediately stood out. They were approximately 2 x 1 m and 2 x 2 m, and did not continue all the way to the surface; instead they appeared to start underneath a thin resistive layer that was interpreted as the fill added to the site after the hole was dug.

Even though we could see from the data that a hole had been dug at this location, there was no way of knowing whether this feature was a grave. I passed on my findings to detectives from the Major Crime Investigation Section at SA Police, and they made the decision to excavate the site.

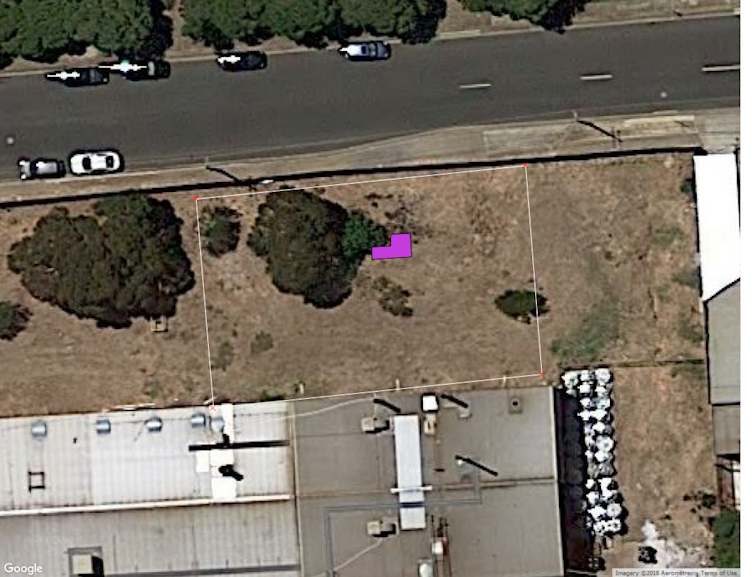

The location of the soil disturbance on the New Castalloy site which was excavated on 2 February 2018.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

The location of the soil disturbance on the New Castalloy site which was excavated on 2 February 2018.

Channel 7, Author provided (No reuse)

The excavation took place on February 2nd. It uncovered fill brought on to the site to aid construction of the nearby building, and then a sandy layer which was found to contain a feature made up of a variety of rubbish including broken ceramic, shell and animal bone. The feature was also wetter than the surrounding sand. This feature corresponded almost exactly in size and shape to the feature found during the ERT survey. No human remains were discovered and the clay layer underneath the feature we found was clearly not disturbed.

Can geophysics help solve crime?

In this case, the close correspondence between buried materials found in the subsurface of the New Castalloy site and the feature shown using ERT validate the use of this technique for finding disturbances underground.

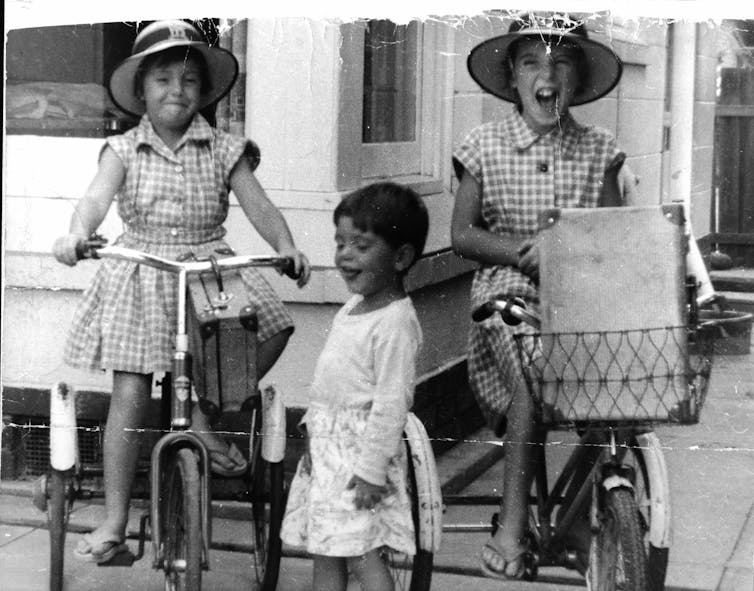

The Beaumont children who went missing in 1966.

Supplied by South Australia Police

The Beaumont children who went missing in 1966.

Supplied by South Australia Police

It sadly did not find Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont on this occasion, but is now established as an appropriate technique for other sites with complicated sub-surface conditions.

Authors: Ian Moffat, ARC DECRA Research Fellow in Archaeological Science, Flinders University