China’s Social Credit System puts its people under pressure to be model citizens

- Written by Meg Jing Zeng, PhD candidate, Queensland University of Technology

In less than a month, China’s Lunar New Year will bring the country’s annual epic travel rush – the largest human migration on earth.

While many are planning trips to their home towns to attend family reunions, millions more Chinese citizens have been blacklisted by authorities, labelled as “not qualified” to book flights or high-speed train tickets.

This citizen ranking and blacklisting mechanism is a pilot scheme of China’s Social Credit System. With a mission to “raise the awareness of integrity and the level of trustworthiness of Chinese society”, the Chinese government is planning to launch the system nationwide by 2020 to rate the trustworthiness of its 1.4 billion citizens.

What ‘credit’ means in China

The word “credit” in Chinese – xinyong (信用) – is a core tenet of traditional Confucian ethics, which can be traced back to the late 4th century BC. In its original context, xinyong is a moral concept that indicates one’s honesty and trustworthiness. In the past few decades, its meaning has been extended to include financial creditworthiness.

So what does “credit” mean in the Social Credit System?

It is a question Chinese authorities have been exploring for more than 10 years. When the plan of constructing a Social Credit System was first proposed in 2007, the primary goal was to restore market order by leveraging the financial creditworthiness of businesses and individuals.

Gradually the scope of the project has infiltrated other aspects of daily life.

Actions that can now harm one’s personal credit record include not showing up to a restaurant without having cancelled the reservation, cheating in online games, leaving false product reviews, and jaywalking.

Ninan Transport Police demonstrates how facial recognition is used to identify pedestrians jaywalking.

Nanjin Transport Police's public Weibo post

Ninan Transport Police demonstrates how facial recognition is used to identify pedestrians jaywalking.

Nanjin Transport Police's public Weibo post

Read more: China's dystopian social credit system is a harbinger of the global age of the algorithm

Reaping rewards for ‘good deeds’

One shared focus of the country’s existing pilot schemes is to generate a standardised reward and punishment system based on a citizen’s credit score.

A Chinese citizen showing her ‘trustworthy card’

Henan Broadcasting's public Weibo post

A Chinese citizen showing her ‘trustworthy card’

Henan Broadcasting's public Weibo post

Most pilot cities have used a points system, whereby everyone starts off with a baseline of 100 points. Citizens can earn bonus points up to the value of 200 by performing “good deeds”, such as engaging in charity work or separating and recycling rubbish. In Suzhou city, for example, one can earn six points for donating blood.

Being a “good citizen” is well rewarded. In some regions, citizens with high social credit scores can enjoy free gym facilities, cheaper public transport, and shorter wait times in hospitals. Those with low scores, on the other hand, may face restrictions to their travel and public service access.

At this stage, scores are connected to a citizen’s identification card number. But the Chinese internet court has proposed an online identification system connected to social media accounts.

Read more: Thinking of taking up WeChat? Here's what you need to know

Naming and shaming of blacklisted citizens

Publishing the details of blacklisted citizens online is a common practice, but some cities choose to take public shaming to another level.

Several provinces have been using TV and LED screens in public spaces to expose people. In some regions authorities have remotely personalised the dial tones of blacklisted debtors so that callers will hear a message akin to: “the person you are calling is a dishonest debtor.”

Blacklisted debtor displayed on a LED screen in Taishan city.

Taishan Government via WeChat

Blacklisted debtor displayed on a LED screen in Taishan city.

Taishan Government via WeChat

It is important for a country to be able to enforce court orders, but when the judicial and legislative systems sometimes malfunction, as they do in China, it raises questions about whether the ability to expose and punish without due process can lead to abuses of power.

Liu Hu, a vocal journalist who has criticised government officials on social media, was accused of “spreading rumour and defamation”. While seeking legal redress in early 2017, he realised that he was blacklisted as “untrusworthy” and prohibited from purchasing plane tickets.

Liu’s story may be an isolated incident, but it demonstrates how the system could potentially be used to push the government’s agenda and to crack down on dissent.

Read more: What we can expect from China's economy in 2018

Harnessing the power of big data

The role of big data in the project has received broad media attention outside China due to concerns about how the Chinese government may use its power to further intensify surveillance.

For example, Chinese tech giants Alibaba and Tencent are testing user credit files based on behavioural data gathered through people’s use of social media and e-commerce sites. To date, few operational details have been released about the country’s plan to integrate user data from online platforms into a central system overseen by the government.

This will soon change. Since last December, the National Development and Reform Commission and Central Bank of China began to approve pilot plans to integrate big data with the Social Credit System. As one of China’s first pilot provinces, Guizhou province was selected to showcase a government-led experiment of a big data-empowered Social Credit System.

Guizhou is one of the poorest provinces in China, and is mostly known for being the home of Maotai – a high-quality liquor. This seemingly random choice of location is actually tactical. Unbeknown to most, since 2015 this rural backwater has been fast becoming the country’s hub of big data.

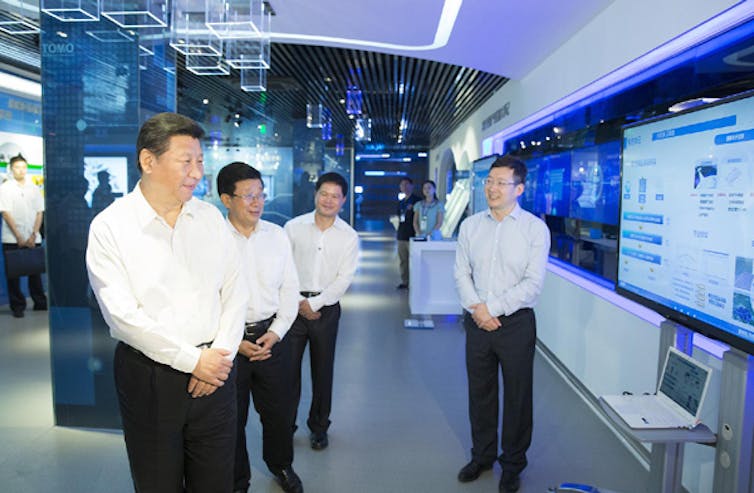

Xi Jinping visiting the big data pilot zone in Guizhou.

Xinhua News

Xi Jinping visiting the big data pilot zone in Guizhou.

Xinhua News

In 2017, tech giants Google, Microsoft, Baidu, Huawei and Alibaba established research facilities and data centres in the region. In 2018, Apple is following suit and transferring its Chinese iCloud server to a local company.

Guizhou’s position as the country’s data centre makes it an ideal social laboratory for the local government’s Social Credit System experiments.

Turning the system back on the government

While some might view China’s Social Credit System as something out of dystopian fiction, if properly implemented the system can have positive impacts – especially when used to keep government officials and business owners accountable.

Most pilot schemes target companies as stringently as individuals. Firms with a history of environmental damage or product safety concerns are now regularly exposed on online blacklists.

Government officials can also be found on online blacklists. As of December 2017, more than 1,100 government officials had been blacklisted as untrustworthy. Such a move to expose corruption is arguably more beneficial to Chinese society than public shaming of jaywalkers.

As Professor Du Liqun of Peking University argues, in the Chinese context the construction of a Social Credit System should start with building a trustworthy government.

Authors: Meg Jing Zeng, PhD candidate, Queensland University of Technology