The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time trades deadpan for high-octane

- Written by Sandra D'urso, Researcher, The Australian Centre, University of Melbourne

The National Theatre’s production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, currently playing at the Arts Centre Melbourne with MTC, is a lauded adaptation of Mark Haddon’s debut novel, of the same title. Haddon’s book was published to much acclaim in 2003. Its literary innovation is in part due to the author’s dead-pan characterisation of the internal monologue of 15-year-old protagonist, Christopher Boone, whom the reader is led to assume is neurologically atypical.

Publicity for the novel referred to the young protagonist, Christopher, as having Asperger’s Syndrome, something that in hindsight, the author “slightly regrets”. Rather, Haddon insists that The Curious Incident is “a novel about difference, about being an outsider, about seeing the world in a surprising and revealing way”.

The novel was adapted by British playwright, Simon Stephens, known for his inventive dramatization of bleak social realities, and ability to theatricalise inner-monologues. Stephens’s adaptation is faithful to Haddon’s novel – it shows Christopher’s love of mathematics, his instinctive recoiling from human touch, insistence on the truth, and unbridled capacity for memorising detail.

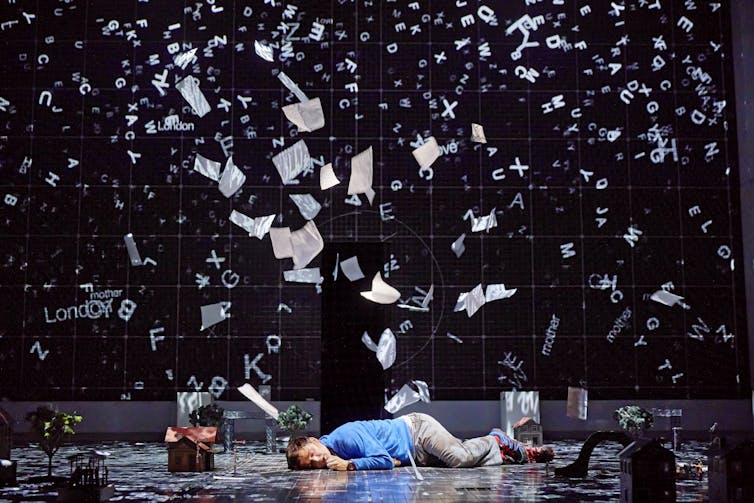

Joshua Jenkins as Christophe Boone on the hi-tech set, which stands in for Christopher’s inner-world.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

Joshua Jenkins as Christophe Boone on the hi-tech set, which stands in for Christopher’s inner-world.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

The direction, by Marianne Elliott, emphasises elements of humour, creating characters that seem larger than life. It is a very affirmative interpretation, and at times is deeply sentimental.

The hi-tech set, which stands in for Christopher’s inner-world, is impressive. The walls and floor are overlaid with perfect grids, an expression of the “infinite” in mathematical thought. In the centre, lies the taxidermied body of a Golden Retriever with a garden fork wedged through its torso; the dog’s wound is denoted by a dark, glittery stain.

The play runs for approximately two and a half hours, and is divided into two parts. It opens with Christopher’s discovery of the dead dog. The puzzle of the pet’s grisly demise provides the whodunnit crime narrative structure, which informs its dramatic arc. An ensemble cast of ten actors, all adept physical performers, plays multiple roles, including neighbourhood characters, commuters, policemen and a station guard.

The first part follows Christopher (Joshua Jenkins) as he investigates the dog’s death. Inspired by Sherlock Holmes, he surmises that the crime is performed by someone “known to the victim”. The dog, Wellington, belongs to a neighbour, Mrs Shears (Amanda Posener), whom we later learn has been in a relationship with Christopher’s father, Ed (David Michaels).

Emma Beattie (as Judy) and ensemble.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

Emma Beattie (as Judy) and ensemble.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

The animated dialogue is matched by the pacey stage directions, which have actors darting across the stage like syncopated clock-work. The main action is interspersed with slower, more lyrical, choreographed sequences, suggesting the slowing down of time, and delving into memory.

We also see Christopher’s exchanges with his sympathetic teacher, Siobhan (Julie Hale), who sometimes doubles as one of his internal voices. While they discuss Christopher’s covert investigation into the crime – Ed has warned his son to “stay out of people’s business” – Christopher opts to bend the rules, and documents his investigation in a book.

Then Ed discovers the forbidden book, igniting his rage. This results in an altercation staged as a highly choreographed tussle between father and son. It includes a sequence of gut-wrenching slaps and punches – a testament to the play’s movement directors, Scott Graham and Steven Hoggett of Frantic Assembly.

By way of apology, Ed concedes that he killed Wellington. Furthermore, Christopher discovers his father has lied about the death of his mother, Judy (Emma Beattie), who lives in London with Mr Shears. As Christopher’s conflicted mother, Beattie delivers a more naturalistic performance, which captures the more nuanced aspects of conflict in the story, as well as its emotional cadences.

Upon learning these shocking facts, Christopher’s sense of safety dissolves, and the stage – a reflection of his fracturing inner-world – erupts in a volley of deafening sounds, screams, and pulses of blinding light.

The second part details the events of Christopher’s perilous train journey from Swindon to London, to escape his father, and find his mother. On his way, he stops off at school and discovers Siobhan wants to make his detective novel into a school play.

“I don’t like acting, it’s a kind of lie”, responds Christopher. This is the one intervention Stephens makes into the book’s narrative, a kind of humorous allusion to the form of “a play within a play”.

Matt Wilman and Johsua Jenkins: Most of part two takes place at the train station, and is it here that the hi-tech set, and exacting choreography come to the fore.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

Matt Wilman and Johsua Jenkins: Most of part two takes place at the train station, and is it here that the hi-tech set, and exacting choreography come to the fore.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

The line is delivered as a joke. At times, I found the comedic delivery of text and characterisation an elision of the undercurrent of menace and violence in the story. After all, Ed has killed his girlfriend’s dog in a jealous rage and Christopher, terrified, is the subject of police and community ridicule.

Most of part two takes place at the train station, and is it here that the hi-tech set, and exacting choreography come to the fore. It is a thrilling mix of sound, lighting and projection, adding to the atmospherics of Christopher’s anxiety.

Ultimately, the young protagonist emerges unscathed; he finds his mother and makes it back to Swindon in time to take his A-level maths exam.

Joshua Jenkins, Matt Wilman and Crystal Condie.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

Joshua Jenkins, Matt Wilman and Crystal Condie.

Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

The play demands high-octane performances of the ensemble cast, especially Joshua Jenkins as Christopher, who is present for its entire duration. Jenkins’s delivery is expressive and energised, but a far-cry from the “dead-pan” delivery and granular vision indicative of the novel’s characterisation of Christopher.

I’m curious about the choice to cast an older actor, who can play “young”, rather than an actor of a similar age to Christopher.

It seems like an unintentionally absurd, if not entirely patronising choice. This is not intended as a critique of Jenkins’s skill as an actor, but an acknowledgement of the fierce intelligence and sensitivity often displayed by young actors. (I’m thinking here of the striking performances in the TV series Stranger Things. In a theatrical context there is Australian theatre company Fraught Outfit, who include children and teenaged performers to stunning effect).

The play concludes with a triumphant Christopher who makes a list of his achievements: He solved a murder, wrote a book, caught a train to London, found his mother and blitzed his A-level maths exam. He turns to Siobhan and asks a difficult question, “that means I can do anything, doesn’t it”?

There is a long, silent, pause as Siobhan, looking slightly downcast, considers her answer. She turns, inhales, preparing to speak, but is cut short when the lights go out.

Of all the spectacular moments in The Curious Incident – the high-tech lights, projection, sound, impeccable choreography – it is this tiny moment, showing Siobhan captive to doubt, which truly sticks.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is at Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse until February 25.

Authors: Sandra D'urso, Researcher, The Australian Centre, University of Melbourne