Bennelong brings Turnbull a prized Lego piece – but he still has to build the set

- Written by Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

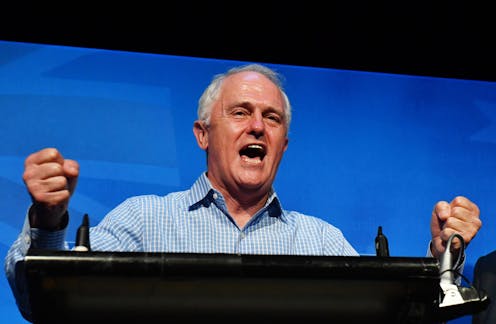

Sometimes Malcolm Turnbull is as transparent as a child. In Bennelong on Saturday night, he was like the four-year-old welcoming Santa. He was full of excitement – fuelled by relief – at a result that, if it had come out badly, could have shaken his leadership to its core.

Over at the Labor gathering, Bill Shorten’s response was carefully calculated. This was a poor outcome for the ALP, given the government’s problems, Labor’s “star” candidate, and the effort Shorten had put into campaigning. But the ALP had readied itself, even before people cast their votes, to translate whatever swing was achieved into the number of seats it would yield if replicated in a national election.

This is the longest of bows, as Labor knows. There can be no meaningful projection, especially when the average swing in byelections is around 5% and, on latest figures, this one is about that.

In terms of the outcome and context, the Bennelong result resembles the 2001 byelection in the Victorian seat of Aston, where an embattled Howard government held onto a seat at a crucial time. The win gave that government a much-needed boost.

Saturday was a big fillip for Turnbull. More so than the New England byelection (where he also looked like the kid for whom Christmas had come), because the result in Barnaby Joyce’s seat was never in doubt.

In tangible terms, the Bennelong outcome means the government is back to majority rule. The most worrying immediate consequence for Labor is that the Coalition can refer to the High Court those Labor MPs it has targeted over their citizenship – and it can prevent its own being sent to judges who have proved punishing.

Also important is that the result takes some pressure off Turnbull’s leadership. He ends the year on as much of a high as possible for a leader who has lost 24 consecutive Newspolls.

In the last few weeks, things have gone Turnbull’s way, just as they’ve gone against Shorten, not least with the Sam Dastyari fiasco.

Same-sex marriage is dealt with as an issue and hailed by Turnbull as his achievement – even if it took a backbench rebellion to get it done, and there is still the religious freedom debate bubbling.

Progress is being made on energy policy, although that has a long way to go.

Monday’s budget update is set to be positive, including gross debt now projected to be A$23 billion less by the end of the forward estimates than was estimated in May. Even the pressure for a royal commission on banks has been responded to, albeit only thanks to another backbench revolt.

Shorten won’t be fooling himself with his own spin. The early part of 2018 could be a nightmare for Labor if it faces byelections. This is likely in Batman in Victoria at least, and perhaps in several seats.

Batman could well be lost to the Greens, which would be a disaster for the ALP; a byelection in the Queensland seat of Longman could also be problematic for Labor.

Those in the opposition who are critical of Shorten can note that it would have been better if he had let the positions of ALP MPs be clarified this year rather than next.

It is undeniable from polling and focus groups that Shorten will not go into the election, due in 2019, on a wave of personal popularity. If he wins – and he’s favourite at this moment, Bennelong notwithstanding – it would be on the basis of the government’s unpopularity and disunity, and Labor’s strong policy pitch and relative cohesion.

Whether the “unity” factor will continue to be as bad for the government and as good for Labor in 2018 remains to be seen. There will be, or should be, pressure on the Coalition conservatives and disruptors to behave better after the marriage result and, for that matter, the Bennelong showing. But they often put ideology, and in some cases bloody-mindedness about Turnbull, ahead of the good of the government, so there is no guarantee.

On the other side, Labor’s unity partly depends on the political dynamics going well for it.

From the government’s point of view, while it can look to Bennelong as a modern Aston, it can’t carry the comparison with 2001 too far. Though some would dispute this, I believe that while Aston became of symbol of the Howard government’s resurrection, it would not have won the 2001 election if it had not been for the extraordinary circumstances of the Tampa affair and the September 11 attacks in the US.

In Turnbull’s case, if history is to see Bennelong as some sort of turning point, his government will have to make it so by its performance over the next year. Bennelong has brought Turnbull a crucial Christmas Lego piece – he still has to assemble the set.

Turnbull’s next political challenge is his ministerial reshuffle, both an opportunity and a risk because there will be winners and losers.

He wants to freshen the team, promote younger talent, and hand out some rewards.

Peter Dutton is already set to step into the new mega home affairs portfolio. Turnbull would also like to promote the very competent finance minister Mathias Cormann to Senate leader, and hence wants the incumbent, Attorney-General George Brandis, to become high commissioner in London.

Brandis, who earlier was one of the more accident-prone ministers, has recently done well and would be going out on a high. He played a significant role in the same-sex marriage issue and has brought to fruition legislation to combat foreign interference.

One who’d not be unhappy to see him leave would be Dutton – Brandis lost ASIO to Dutton but retained some checks for the attorney-general.

Brandis is understood to be concerned that his departure would significantly diminish the voice and clout of the moderates, while also reducing the influence of Queensland – a state that will be vital to the Coalition at the election – in the highest levels of the government. On the basis of merit, there is no obvious Queensland replacement for promotion into cabinet.

As well, the government has yet to shepherd the foreign interference legislation through, which is not without its own controversy.

Of course, Turnbull will have the last word on Brandis. If he were wise, he’d leave him where he is.

Authors: Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra