Guide to the Classics: Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars explores vice and virtue in ancient Rome

- Written by Caillan Davenport, Lecturer in Roman History and ARC DECRA Research Fellow, Macquarie University

In a memorable scene from the classic BBC TV series I, Claudius (1976), three frightened senators are summoned to the palace in the dead of night by the emperor Caligula. Rather than being executed, they are treated to a command performance by Caligula himself, who dances before them dressed in a shimmering gold bikini.

Caligula’s midnight dance routine is the climax of a sequence of horrors and indiscretions committed by the emperor. He has his predecessor suffocated to death with a pillow, executes his cousin because of his irritating cough, and engages in an incestuous relationship with his sister (they’re both gods, you see).

Caligula dances for Claudius and two other senators. Scene from the BBC TV series, I, Claudius (1976).These outlandish scenes cannot be ascribed to the imagination of the scriptwriter Jack Pulman or to Robert Graves, the author of the original novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God, on which the series is based. The incidents are adapted from Suetonius’s On the Lives of the Caesars, a collection of imperial biographies written in Latin in the second century A.D.

Latin edition of The Twelve Caesars published in 1541.

Wikimedia Commons

Suetonius’s work describes the lives of Rome’s first 12 leaders from Julius Caesar to Domitian - hence it is best known today as The Twelve Caesars. This is the title it bears in the paperback Penguin Classics edition, translated by Robert Graves himself in 1957, and still in print today.

Latin edition of The Twelve Caesars published in 1541.

Wikimedia Commons

Suetonius’s work describes the lives of Rome’s first 12 leaders from Julius Caesar to Domitian - hence it is best known today as The Twelve Caesars. This is the title it bears in the paperback Penguin Classics edition, translated by Robert Graves himself in 1957, and still in print today.

Suetonius’s unforgettable tales of sex, scandal, and debauchery have ensured that his writing has played a significant role in shaping our perceptions of imperial Rome.

The man and the work

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus was a scholar and intellectual who held administrative positions at the imperial court under the emperors Trajan and Hadrian. He was a prolific author, writing biographies of poets and orators, as well as works on topics as diverse as the games, the Roman year, bodily defects, and lives of famous courtesans.

He probably began to write the Caesars when he was Hadrian’s secretary of correspondence. However, the biographies were only published after Suetonius was dismissed from Hadrian’s service for being too familiar with the emperor’s wife.

Bust of Hadrian in the Musei Capitolini.

Wikimedia Commons

Bust of Hadrian in the Musei Capitolini.

Wikimedia Commons

Political expediency meant that Suetonius wisely avoided writing about Hadrian. Instead The Twelve Caesars includes the Julio-Claudians, Rome’s first imperial dynasty (Julius Caesar, Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero), three short-lived emperors during the civil wars of A.D. 69 (Galba, Vespasian, Otho), and the Flavian dynasty (Vespasian, Titus, Domitian).

The structure of the individual biographies has often puzzled modern readers, who expect Suetonius to tell his story in a linear fashion from birth to death. Although Suetonius usually begins with an emperor’s family and upbringing, the bulk of each Life consists of an assortment of memorable, and sometimes salacious, anecdotes about an emperor’s public conduct and private life.

But this is no mere haphazard catalogue of sex and corruption. Instead, Suetonius tells his readers that he has carefully organized the stories “by categories”. These categories include the emperor’s virtues (such as justice, self-control, and generosity) and his vices (like greed, cruelty, and sexual excess).

Virtues and vices

In the second century A.D., when Suetonius was writing, there was no chance of a return to the Republic, but aristocrats still expected the emperor to behave as if he were merely the most prestigious citizen rather than an autocrat. The stories of virtue and vice in the Caesars are carefully selected to illustrate whether emperors measured up to this standard.

When Suetonius describes an emperor’s ancestors, he highlights how their qualities influenced the ruler himself. Early in the Life of Nero, the reader encounters Nero’s grandfather who staged particularly cruel shows in the arena. This helps to explain the later tales of Nero’s own savagery, because the reader would see that this vice was part of his nature.

Suetonius is fair and evenhanded in his treatment of his subjects. All emperors appear as flawed men with both virtues and vices, but the balance between them depends on the individual ruler. He even gives due credit to the notorious Caligula, who began his reign by publishing the imperial budget and showing generosity to the people. Suetonius then signals a change:

Thus far, it is as if we have been writing about an emperor, but the rest must be about a monster.

This “division” – a statement in which Suetonius clearly separates the anecdotes illustrating virtues from the vices – is a feature of several of his biographies. In Caligula’s case, it is from this point on that we read about his pretensions to divinity, his condemnation of aristocrats to hard labour in the mines, and his sexual immorality.

Emperor Tiberius, played by George Baker, in I Claudius.The tales of the emperors’ sexual habits constitute some of the most famous passages in Suetonius. He chronicles Tiberius’s sordid behaviour on Capri, detailing how he forced men and women to engage in threesomes, had children perform oral sex on him, and raped young men who took his fancy.

When the Loeb Classical Library, which features the original Latin and the English translation of classical texts on facing pages, published their first edition of Suetonius in 1913, these chapters about Tiberius’s behaviour were left in Latin because they were considered too scandalous to translate. Although they are now translated into English, these graphic tales still have the power to shock and unsettle the reader.

An emperor’s private life and his sexual conduct were fair game because they reflected whether or not he was fit to rule. The same applied to members of his family. Augustus’s daughters were praised by Suetonius for spending their time weaving in his house. (Such gender stereotypes remain with us today, if one recalls the photo shoot of Julia Gillard knitting in Women’s Weekly). When his daughter Julia flagrantly flouted Augustus’s own adultery legislation, Suetonius reports that he had no choice but to exile her. The imperial family had to set standards for the entire empire.

Man or god?

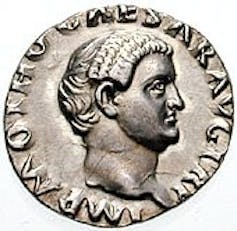

Silver coin of the emperor Otho.

Wikimedia Commons

Silver coin of the emperor Otho.

Wikimedia Commons

After the virtues and vices, Suetonius’s Lives usually conclude with a narrative of the emperor’s death and a detailed physical description of his body. Suetonius didn’t hold back in these passages, even pointing out that the emperor Otho sported a terrible wig to hide his bald patch (as his coinage also reveals).

The description of the emperor Nero is particularly memorable:

He was of a good height but his body was blotchy and ill-smelling. His hair was fairish, his face handsome rather than attractive, his eyes bluish-grey and dull, his neck thick, his stomach protruding, his legs very thin…

The different body parts were supposed to indicate character traits. Nero’s blotchy skin likened him to a panther (regarded as a deceitful creature); his hair colour suggested courage; the bulging beer belly had connotations of power, but also exposed his devotion to pleasure; his feeble legs indicated both femininity and fear. Nero was thus revealed to be a contradiction.

The emperor Claudius as Jupiter, Vatican Museum.

Wikimedia Commons

The emperor Claudius as Jupiter, Vatican Museum.

Wikimedia Commons

The descriptions of the bodies are also very funny. They undercut the divine pretensions of emperors, whose statues showed them in heroic nudity with six-packs that demonstrated their virility and likened them to gods. (Once again, not much has changed, as revealed by the images of Vladimir Putin’s shirtless hunting expeditions or Tony Abbott in his budgie smugglers).

Suetonius’s stories about the emperors’ faults and foibles exposed them as human beings. He even collected their famous sayings to shed light on their character – the famous line “as quick as boiled asparagus”, intoned beautifully by Brian Blessed’s Augustus in I, Claudius, is straight out of Suetonius.

His account of the witty sayings of Vespasian shows that the emperor frequently joked about his own economic policies:

When his son Titus criticized him for putting a tax even on urine, he held up a coin from the first payment to his son’s nose and asked him if he was offended by its smell. When Titus said no, he observed: ‘But it comes from urine.’

Vespasian emerges as a rather avuncular figure. He even pokes fun at the deification of emperors, proclaiming in the days before his death, “Oh dear, I think I am becoming a god!”

Laughing at power

But the humour of Suetonius’s Caesars is often double-edged. He tells one story about the time Nero visited his aunt on her death bed, and she lovingly remarked that she would die happy once she had the hairs from the first shaving of his beard. Nero joked that he would shave it off immediately. He then gave his aunt an overdose of laxatives to kill her off and seized her estate for himself.

Head of Nero, with beard, from the Palatine Museum.

Wikimedia Commons

Head of Nero, with beard, from the Palatine Museum.

Wikimedia Commons

Roman aristocrats reading this tale would probably have laughed, given its absurdly comic elements. But it would have been nervous laughter. For such stories reminded them of the power of the emperor. While they might have chuckled at another’s misfortune, they would have been acutely aware that one day it could be them.

Suetonius’s Caesars is thus more than a haphazard collection of gossip and scandal, but a work that sheds light on the world of the Roman aristocracy and how they lived (and coped) with their emperors. The stories of the emperors’ virtues and vices illustrates what Roman elites considered to be acceptable behaviour by their leaders.

Suetonius’s biographies also cut the emperors down to size, revealing them to be men with human flaws, rather than gods. They offered a necessary means of escapism in a world where imperial fickleness could end one’s career – or one’s life.

Recommended translation: Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, Oxford World’s Classics edition by Catharine Edwards (2008).

Authors: Caillan Davenport, Lecturer in Roman History and ARC DECRA Research Fellow, Macquarie University