The dual citizenship saga shows our Constitution must be changed, and now

- Written by Joe McIntyre, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of South Australia

It is time to accept that section 44 of the Australian Constitution is irretrievably broken. In its current form, it is creating chaos that is consuming our politicians. This presents a rare opportunity for constitutional change. A referendum could address not only the citizenship issue but the entirety of section 44, which no longer looks fit for purpose.

The “brutal literalism” adopted by the High Court means that there can be no quick or stable resolution to the citizenship saga consuming the national political class.

Even a thorough “audit” of current politicians, such as the deal announced this week by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, will offer only a temporary respite. Not only can it be extremely difficult to determine if someone has foreign citizenship, the agreed disclosures will not capture all potential issues (for example, it only extends back to grandparents). Moreover, as foreign citizenship is dependent on foreign law, a foreign court decision or legislation may subsequently render a person ineligible.

This issue will continue to dog all future parliaments.

The idea that the Constitution provided a “flashing red light” on this issue is mistaken. The dual citizenship problem has long been an open secret. It has been the subject of numerous parliamentary reports over the last 40 years, the most recent in 1997.

A royal commission was once suggested to audit all politicians. This has been a time bomb waiting to go off, but one that stayed strangely inert for over 100 years.

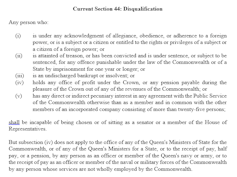

Current version of section 44.

Current version of section 44.

Moreover, no one really knew how the High Court would resolve the “Citizenship 7” case. The PM was widely mocked for his initial certainty about Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce’s eligibility.

Following the High Court’s unexpected same-sex marriage decision, few commentators felt any confidence in predicting how it would decide the “Citizenship 7” case. The result could easily have gone the other way.

More significantly, the court has imposed a far harsher test than expected. Not only is knowledge of potential ineligibility irrelevant, it is not sufficient that a person takes “reasonable steps” to divest foreign citizenship. Unless a foreign law would “irredeemably” prevent a person from participating in representative government, the fact of dual citizenship will be sufficient to disqualify a person.

It is this strict new interpretation that has cast doubt over the eligibility of politicians such as Labor MP Justine Keay. Keay had renounced her British citizenship prior to nomination, but did not receive final notification until after the election. Arguably, she is ineligible. This was not a failure to undertake “serious reflection”, but a consequence of it.

Prospective politicians would be required to irrevocably rid themselves of dual citizenship early enough to ensure this is confirmed prior to nomination. The Bennelong byelection provides a graphic illustration of the issue – the ten days between the issuing of the writs and the close of nominations would be far too short for any effective renunciation.

Serious unresolved issues remain, even before we get into the difficulty posed by the “entitled to” restriction in section 44. This provision could, for example, render Jewish politicians ineligible under Israel’s “right of return” laws.

Section 44 is not only unworkable, it is undesirable. The spectre of Indigenous leader Patrick Dodson being potentially ineligible, or Josh Frydenberg facing questions after his mother fled the Holocaust, reveal the moral absurdity of this provision. In a modern multicultural society, where citizenship rights are collected to ease travel and work rights, a blanket prohibition is archaic and inappropriate.

Perhaps by giving us an (unnecessarily) unworkable interpretation, the High Court has unwittingly provided the impetus to reform the entirety of section 44.

That section is concerned with more than just citizenship. Disqualifying attributes including jobs in the public service, government business ties, bankruptcy and criminality.

In disqualifying Senators Bob Day and Rod Culleton earlier this year, the High Court again interpreted the provisions unexpectedly strictly. Again, this strict interpretation has invited challenges to other politicians.

Under the current law, it seems a potential candidate must irrevocably rid themselves of all (potentially valuable) disqualifying attributes prior to nominating, on the chance they may be elected. Jeremy Gans, one of the most vocal critics of the High Court’s decision, has described this as “one of the Constitution’s cruellest details”. Moreover, as Hollie Hughes’s case illustrates, a defeated candidate may need to avoid these activities even after the election on the off chance of a recount.

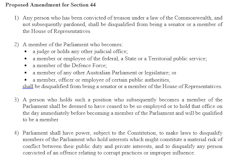

Proposed version of section 44.

Proposed version of section 44.

Constitutional change offers a chance to break this deadlock. The process does not need to be long and convoluted. We already have a draft text. The proposal suggested by the 1988 Constitution Commission scrapped all disqualifications except the prohibition on treason, and offered a reworked restriction on employment. Other matters would be left to parliament

This well-considered proposal is compelling. We could have an act passed by Christmas, and a referendum early in the new year. The same-sex marriage survey, a matter that will affect many more people far more substantially, has been organised and executed in a far shorter time.

This is a technical issue, but it is consuming vital public resources and distracting our politicians from the role of governing Australia. Changing the Constitution is the only way to draw a line under this chaos.

Our Constitution was never meant to be a static document. It is now over 40 years since we successfully amended the Constitution, and nearly 20 years since a referendum was even held. Both of these are record periods of time for our Federation.

This has perpetuated the myth that constitutional change is effectively implausible. A referendum on section 44 would re-engage the Australian people in this vital process. This will, in turn, make it easier for other causes, including Indigenous rights and the republic, to be taken to referendum.

Authors: Joe McIntyre, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of South Australia