Support for standardised tests boils down to beliefs about who benefits from it

- Written by John Munro, Professor, Faculty of Education and Arts, Australian Catholic University

Since it was introduced in the 1800s, standardised testing in Australian schools has attracted controversy and divided opinion. In this series, we examine its pros and cons, including appropriate uses for standardised tests and which students are disadvantaged by them.

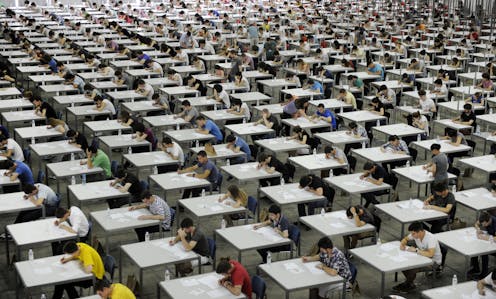

If any topic is likely to divide a room of individuals interested in education, it is the use of standardised assessment. A standardised test is any test that requires all test-takers to respond to the same tasks in the same way. It is administered in a consistent manner and scored using a scale of standards in knowledge and skills. One example is NAPLAN.

Standardised tests have been used in Australia for approximately 200 years

Standardised testing began in Australia in the 1800s. Itinerant school inspectors used it to monitor the quality of education being provided. External examinations boards assessed student achievement on sets of tasks in primary, secondary and tertiary education.

In the early 1900s, it was also used to assess learning ability. The famous “mazes” tasks, a psychological test designed to measure psychological planning capacity and foresight, were used in many international intelligence assessments. They were first developed by Stanley Porteus, the inaugural principal of the first state special school in Victoria in 1913 as part of a range of screening tools.

The threat of the USA losing the space race in the 1950-60s led to a focus on the quality of educational outcomes. Standardised assessment procedures were used nationally to monitor this. Over the decades since, testing has become more frequent and more centralised, with a shift to making schools and educators accountable for scores.

Five narratives that influence support for standardised testing

Reasons for and against their use in these and other ways are numerous.

Our opinions and views on this issue are shaped by the dialogue in which we participate. In 2017, Jensen and colleagues analysed the perspectives of over 120 prominent authors from the domains of education, policy, economic, psychology/psychometry and history, published across the last century. They identified the most common narratives each domain and its consequences. The most common theme of all domains is its use to control education. They differ in their disposition to this control and how it is implemented:

The education domain sees this as a political and negative control mechanism. Its dialogue rarely explores how testing can benefit the educational process.

The policy domain sees control as positive. Standardised tests provide “pure”, “trustworthy” measures of achievement that have improved school accountability, classroom practices and learning.

The economic domain also sees it as positive. Standardised test data predict economic outcomes. Policy makers use these economic analyses more than educators, especially practitioners.

The psychology/psychometry domain notes the frequent inappropriate use of standardised tests, with misinterpreted outcomes. For example, the belief that test scores are precise and can be interpreted as such.

The history discipline sees testing used to control what is valued as knowledge (the curriculum), who gets to learn it (sorting and selecting students) and school organisation and teaching practices. It discusses how testing is used to make teachers and pupils accountable.

Four additional stakeholders with a voice in education not examined directly by this research are parents, the community, industry and politicians. Phelps, in 2005, noted that in the USA at least, all were strongly committed to it.

In other words, like other concepts in contemporary education, there are multiple perspectives on standardised assessment. Our position on its value, relevance and valid use is informed by our more fundamental beliefs about the purposes of education in a culture, our conception of students, our roles and responsibilities as educators and our understanding of learning and teaching. Awareness of the five narratives can contribute to our personal views about standardised testing.

How is test data used?

One reason for the debate relates to how standardised test data is used. Some of the most common purposes are to inform decisions about:

the knowledge and skills students can display independently at any time,

a student’s learning profile,

the teaching that matches a student’s learning profile,

the additional knowledge and skills a student needs to meet particular educational criteria,

the success or effectiveness of educational provision in a school,

“academic standards” and comparative educational performance between schools, states or countries, and

resourcing educational provision.

Standardised testing is necessary, but not sufficient

Standardised assessment data plays a key role in my work as an educator. Part of this involves identifying the most appropriate learning pathways for students who learn differently from their peers. Standardised assessment data helps me see where and how they differ.

But this is insufficient. I also need to analyse more specifically how each student learns, often using individual interviews and error analysis. I use dynamic assessment procedures to examine how they interpret and respond to regular and to differentiated teaching.

I also need data that standardised assessment procedures have difficulty providing. For example, a student’s emotional engagement with the teaching, their attitudes to it, their identities as learners, their ability to manage and direct their learning activity and how culturally relevant they see the teaching. Standardised assessments contribute to my data collection but are certainly not enough.

Standardised testing is likely to be with us for some time. As educators, many of us object to how and why it is used beyond the teaching-learning context and the preference and priority it is given over other forms of assessment. To ensure that it benefits optimally the learning outcomes of our students, we may need to both broaden our narrative about it and take whatever steps we can to minimise its negative influences.

Authors: John Munro, Professor, Faculty of Education and Arts, Australian Catholic University