Why are talks over an East Antarctic marine park still deadlocked?

- Written by Cassandra Brooks, Assistant Professor Environmental Studies, University of Colorado

Last week, representatives from 24 countries plus the European Union met in Hobart to discuss plans for a vast marine protected area (MPA) off the coast of East Antarctica.

The proposed area, spanning almost 1 million square km, is crucial for a vast array of marine life. Scientists, conservationists and governments have been pushing for the protection of this area for upwards of seven years.

Why, then, has the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) failed to deliver, despite having agreed similar protections for other areas of the Southern Ocean?

Competing national incentives among member states, and complex international relations extending far beyond the negotiations themselves, have stymied consensus as states negotiate power and fishing access in this icy commons at the bottom of the world.

Read more: Why Antarctica depends on Australia and China’s alliance

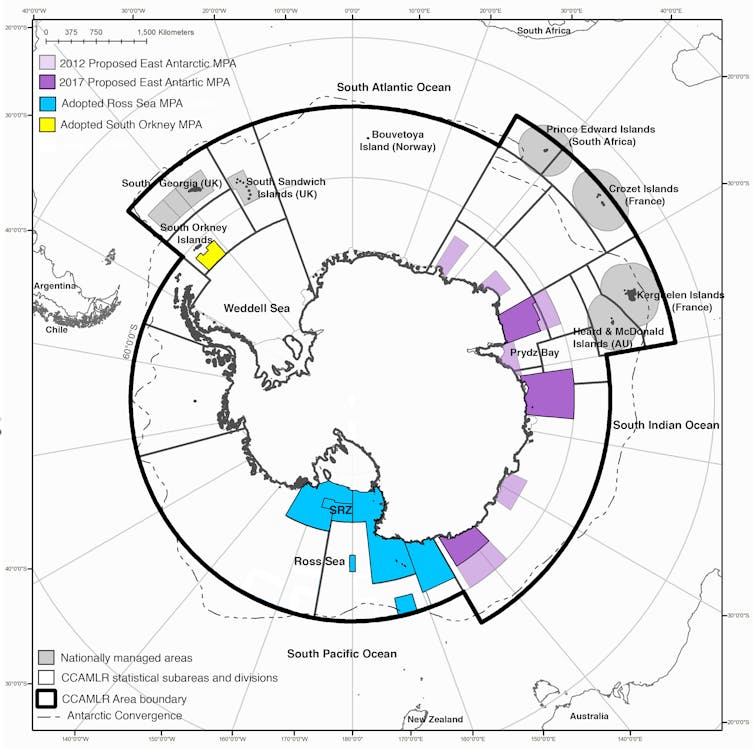

CCAMLR committed to establishing a network of marine parks in the Southern Ocean in 2002 and has enjoyed success. In 2009 it established the world’s first international MPA, covering 94,000 square km south of the South Orkney Islands. Then, in 2016, the Commission made headlines when it successfully negotiated the world’s largest marine park, covering 1.55 million square km in the Ross Sea.

This raised hopes for a similar breakthrough for East Antarctica at this year’s meeting. But those hopes were put on hold for another year.

Vast protections

According to plans first proposed to CCAMLR in 2012 by Australia, France and the EU, the East Antarctic marine park was designed as a representative system of seven marine protected areas, covering 1.8 million square km that would capture key ecosystem processes.

By 2017 the seven zones had been scaled back to three, covering just under 1 million square km – largely to accommodate some member states’ economic interests and political concerns.

CCAMLR current MPAs in the South Orkney Islands (adopted in 2009) and Ross Sea (adopted in 2016) and proposed MPA off the East Antarctic. Original 2012 East Antarctic MPA proposal shown in light purple and current 2017 proposal in dark purple. Figure modified after Brooks et al. 2016.

CCAMLR current MPAs in the South Orkney Islands (adopted in 2009) and Ross Sea (adopted in 2016) and proposed MPA off the East Antarctic. Original 2012 East Antarctic MPA proposal shown in light purple and current 2017 proposal in dark purple. Figure modified after Brooks et al. 2016.

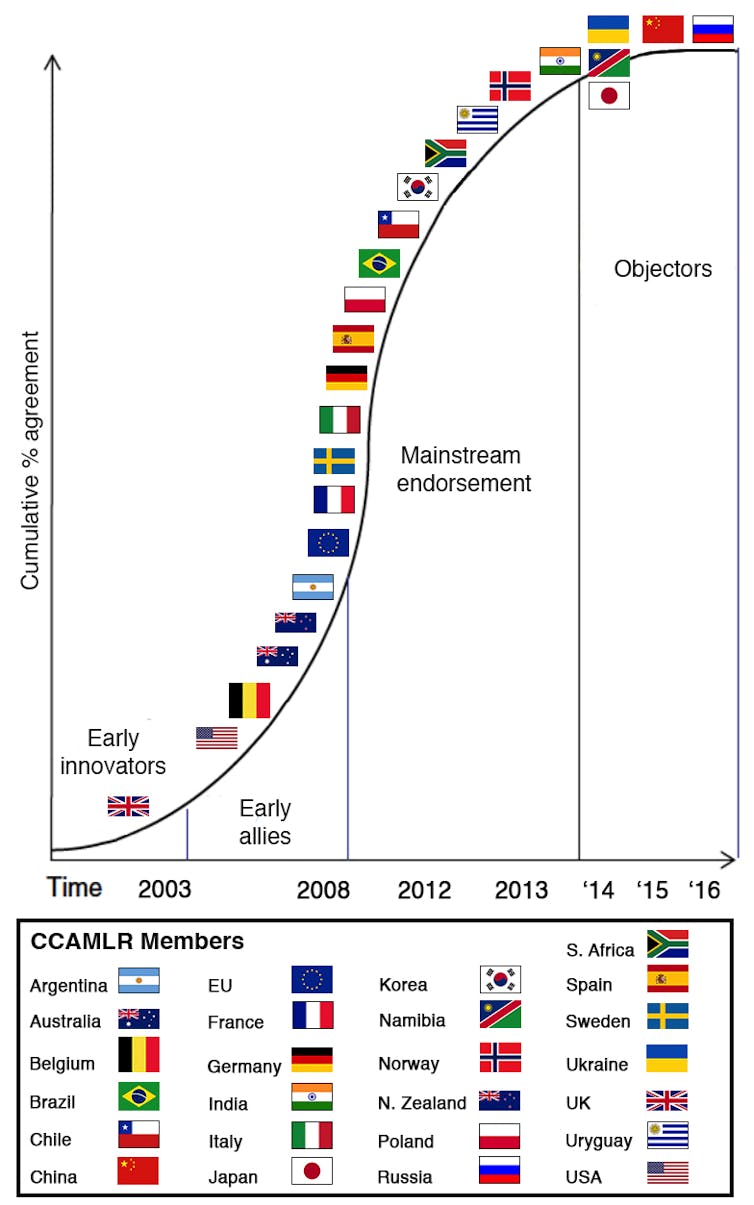

Coming into 2017, proponents had worked to strengthen the East Antarctic MPA proposal, achieving the support of all states except Russia and China.

This obstruction is not novel. These two states have been the most vocal opponents of MPAs throughout the history of the negotiations, citing a variety of concerns including fishing interests, sufficiency of science, conservation need, and political accusations.

Fishing interests

Fishing interests have been a crucial factor in the negotiations, not just for China and Russia but also for the bulk of fishing states, which make up the majority of the Commission.

One of the reasons the South Orkney Islands reserve was adopted swiftly in 2009 was because it did not interfere with current or future fishing interests. Following this precedent, the Ross Sea marine reserve was designed largely around the lucrative fishing grounds for toothfish, and China only agreed to the plans after a krill-fishing zone was added in 2015 – despite the fact that neither China nor any other member state currently fishes for krill in the Ross Sea.

Small toothfish fisheries are scattered throughout the East Antarctic, including within the proposed MPA. However, this proposal has a multiple-use design, and none of the areas are explicitly closed to fishing. Yet some of Russia’s and China’s opposition concerned potential limitations to fishing. Why?

As a commons where sovereignty is suspended under the Antarctic Treaty, the Southern Ocean continues to be a contested space. Fishing can be used as a means to occupy space in this global commons, meeting geopolitical as well economic goals by asserting power and securing future access.

In recent years China has used the debate over MPAs to challenge the intentions of the very CCAMLR Convention as one inherently offering members a right to fish rather than a responsibility to conserve. A new Chinese krill fishing effort in the East Antarctic that initiated last year may be worth more in terms of geopolitics than it is in terms of money.

Finding opportunities to break the deadlock

How can the deadlock be broken? Perhaps negotiators can learn from the success of the Ross Sea marine park plan where high-level diplomacy created a political window of opportunity. China’s support was secured in 2015, after presidential-level bilateral meetings with the United States.

Read more: How China came in from the cold to help set up Antarctica’s vast new marine park

That left Russia as the only nation not to support the plan – a bad look, given that it was preparing to chair the 2016 meeting, and President Vladimir Putin had declared 2017 a special Year of Ecology. Russia had the opportunity and incentives to demonstrate leadership.

But also importantly, the US Secretary of State John Kerry was personally invested in the outcome, and throughout 2016 he had been liaising with his counterparts in Russia. Pressure was building both inside and outside the meeting room. After securing concessions to increase the amount of toothfish fishing in certain zones, Russia eventually approved the plans.

The process of building consensus for adopting CCAMLR MPAs, with particular focus on the Ross Sea MPA during the 2013–2016 time period. Figure modified after Brooks 2017.

The process of building consensus for adopting CCAMLR MPAs, with particular focus on the Ross Sea MPA during the 2013–2016 time period. Figure modified after Brooks 2017.

In managing one of the great oceanic commons, despite political plays, CCAMLR has demonstrated leadership in adopting marine protected areas. The Southern Ocean now harbours the world’s largest marine park in the Ross Sea. Despite the latest setback a proposal for the East Antarctic remains on the table as well as plans for other marine parks in the Weddell Sea and off the Antarctic Peninsula.

Securing international agreements takes patience and it is often unclear in the moment how a political window of opportunity opens. It may still take some time to align national incentives and generate international diplomacy for the East Antarctic MPA and the others to come. The Commission’s 25 members ultimately need to find the political will to see it through.

Authors: Cassandra Brooks, Assistant Professor Environmental Studies, University of Colorado

Read more http://theconversation.com/why-are-talks-over-an-east-antarctic-marine-park-still-deadlocked-86681