Friday essay: the cultural meanings of wild horses

- Written by Michael Adams, Associate Professor of Human Geography, University of Wollongong

I am walking quietly through the forest. As I reach the edge of the trees there is a snort and a staccato of hoofbeats, and four horses materialise only metres in front of me: a foal, two mares and a dark stallion. The stallion, ears pricked, tosses his head and prances forward. As I crouch to pick up a branch, the stallion wheels and gallops off with the group. They hurdle an old stock fence, and almost as soon as their hoofs touch down, another big grey stallion comes towards them over the hill.

The next minutes are completely mesmerising. The two stallions fight, 50 metres from me. Dust hangs in the air around them, their screams echo off the hills, the impact of their hoof strikes reverberates in my belly. They rear, scream; snake heads out to bite, whirl and kick. Eventually, bleeding and bruised, the dark stallion breaks and runs. The grey makes a show of chasing, then canters back to the mares, arching his neck, prancing with lifted tail.

This is one of many times I have seen horses, called brumbies in Australia, in the mountains. While cross-country skiing in the south I have watched them in the snow - ragged manes flying, galloping through a mist of ice crystals - and many times while driving and bushwalking in both the north and south of Kosciuszko National Park. I have also watched them cantering in clouds of dust in central Australia, and grazing in the swamps of Kakadu. Each of these wild horse encounters has been deeply visceral and emotional, elemental expressions of life in dramatic and beautiful landscapes.

Horses are large, powerful and charismatic animals, and humans have ancient connections to them. Wild horses are dominant among the 13 species painted on the caves of Chauvet in France 30,000 years ago, and while there continues to be debate, archaeologists suggest evidence for horse domestication is at least 5,500 years old. And like the oldest human-animal relationship outside hunting - with dogs - the horse relationship is unique because we now mostly do not eat this animal.

Like dogs, horses now occur on every continent except Antarctica, and humans have been the primary agent for their dispersal. In North America, where the first true horses evolved and then died out, they were reintroduced by Columbus in 1493. Horses are the most recent of the main species humans domesticated, and the least different (with cats) from their wild counterparts.

Horses and other animals on the walls of the Chauvet Cave in southern France, from 30,000 years ago.

Claude Valette/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Horses and other animals on the walls of the Chauvet Cave in southern France, from 30,000 years ago.

Claude Valette/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Australia has the largest wild horse herd in the world, maybe 400,000 or more horses, spread across nearly every bioregion from the tropical north to the arid centre to the alpine areas. That sounds like a dramatically large number, but Australia also has around one million domestic horses, about 100 million cattle and sheep, maybe 20 million feral pigs and 25 million kangaroos. But the presence of wild horses here is deeply controversial.

Six thousand of these horses are in Kosciuszko National Park. Ongoing controversy around these wild horses encompasses debate about their impact and their cultural meaning. There is very little systematic research and a large amount of emotive and anecdotal argument, from both sides. There is circularity and self-referencing in government wild horse management plans, very little reference to studies from Australia and almost no peer-reviewed research on horse impacts in the Snowy Mountains, despite decades of argument that they cause environmental degradation.

And Kosciuszko is right next to Canberra and the Australian Capital Territory, which has the highest per capita horse-ownership of anywhere in Australia. Several enterprises run horse-trekking trips into the Snowy Mountains, often interacting with brumbies. The Dalgety and Corryong annual shows on the boundaries of the park highlight horse skills, including catching and gentling brumbies. In many places mountain cattle properties are increasingly using horses instead of motorbikes to handle stock.

The Kosciuszko wild horses are also tangled within the embedded idiosyncrasies and contradictions of the largest national park in New South Wales. Here there are protected populations of two species of invasive fish (brown and rainbow trout) that are demonstrably responsible for local extinctions of native fish and frog species; a gigantic hydro-electric scheme with dominant infrastructure across large areas of the park; and expanding ski resorts where it is possible to buy lodges. Much of the landscape that is now part of the park has a long history of summer grazing by sheep and cattle, with stockworkers’ huts scattered across the high country. This “wilderness” has been home to Aboriginal people for millennia, as well as well-known grazing grounds for more than a century.

These complexities and contradictions reflect our often unconscious modern propensity for hubris: we insist we are in charge of what happens on the planet, including in its “wild” places and “wild” species. Terms like “land management”, “natural resource management”, and “conservation management”, all reflect this assumption of superiority and control.

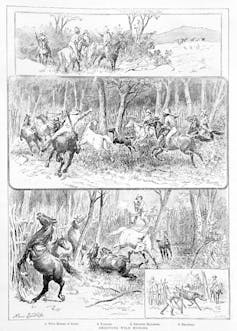

Roping wild horses, Gippsland, Arthur John Waugh, circa 1910-1920.

State Library of Victoria

Roping wild horses, Gippsland, Arthur John Waugh, circa 1910-1920.

State Library of Victoria

Indigenous interactions

The United States has similar controversies over the management of mustangs across large areas of the west. New Zealand has the Kaimanawa horses, a special and isolated herd on army land. In both of those countries, as in Australia, there is a unique history of horse interactions with Indigenous communities. The great Native American horse cultures are well known and extraordinary, as Indians had no introduction to equestrian skills from the Spanish invaders, they learnt extremely quickly from scratch.

The first horses in New Zealand were a gift to Maori communities from missionary Samuel Marsden in 1814, and a Waitangi Tribunal Claim has been brought to protect the Kaimanawa horses as Maori taonga (treasures). Aboriginal stockmen and stockwomen were the mainstay of the pastoral industry all over Australia until the equal wage ruling of 1968 resulted in the wholesale expulsion of Aboriginal stockworkers in north and central Australia.

Peter Mitchell’s recent book Horse Nations uses that term to describe the people-animal relationship in certain Indigenous communities. Both Native American and Aboriginal cosmologies often place animals including horses, as their own “nations”, with whom they have a responsibility to respectfully interact.

Goodreads

The wild horses of the Australian Alps are arguably the strongest cultural icons. The enduring legacy of The Man from Snowy River, both the iconic Banjo Paterson poem and the 1980s film, but also the Silver Brumby series of novels by Elyne Mitchell, still in print after nearly 70 years, idealise the strength, beauty and spirit of wild mountain horses. At least one source suggests that “the man” from Paterson’s poem was in fact a young Aboriginal rider.

This is not at all implausible – there is much documentation, as well as strong oral histories, of Aboriginal men and women working stock on horseback across the Snowy Mountains. The Aboriginal mountain missions at Brungle and Delegate both have many stories of earlier generations working as stock riders and also mustering wild mountain horses. David Dixon, Ngarigo elder, says

Our old people were animal lovers. They would have had great respect for these powerful horse spirits. Our people have always been accepting of visitors to our lands and quite capable of adapting to change so that our visitors can also belong, and have their place.

While the iconic figure of the cowboy and stockman is masculine, amongst Aboriginal stockworkers women and girls were likely as common as men and boys. In contemporary times, women far outnumber men in equestrian participation, and brumby defenders are equally represented by men and women. Four Australian horsewomen generously shared their knowledge and skills in the research that backgrounds this essay.

Animal intelligence

In the mid 1970s, I worked as a ranger in Kosciuszko National Park. In those days rangering was a seat-of-the-pants enterprise: we used to buy at least part of our uniforms out of our own money because the issued items were so inadequate, we taught ourselves to cross-country ski, we drank socially with the brumby-runners and other people from the surrounding rural communities.

Goodreads

The wild horses of the Australian Alps are arguably the strongest cultural icons. The enduring legacy of The Man from Snowy River, both the iconic Banjo Paterson poem and the 1980s film, but also the Silver Brumby series of novels by Elyne Mitchell, still in print after nearly 70 years, idealise the strength, beauty and spirit of wild mountain horses. At least one source suggests that “the man” from Paterson’s poem was in fact a young Aboriginal rider.

This is not at all implausible – there is much documentation, as well as strong oral histories, of Aboriginal men and women working stock on horseback across the Snowy Mountains. The Aboriginal mountain missions at Brungle and Delegate both have many stories of earlier generations working as stock riders and also mustering wild mountain horses. David Dixon, Ngarigo elder, says

Our old people were animal lovers. They would have had great respect for these powerful horse spirits. Our people have always been accepting of visitors to our lands and quite capable of adapting to change so that our visitors can also belong, and have their place.

While the iconic figure of the cowboy and stockman is masculine, amongst Aboriginal stockworkers women and girls were likely as common as men and boys. In contemporary times, women far outnumber men in equestrian participation, and brumby defenders are equally represented by men and women. Four Australian horsewomen generously shared their knowledge and skills in the research that backgrounds this essay.

Animal intelligence

In the mid 1970s, I worked as a ranger in Kosciuszko National Park. In those days rangering was a seat-of-the-pants enterprise: we used to buy at least part of our uniforms out of our own money because the issued items were so inadequate, we taught ourselves to cross-country ski, we drank socially with the brumby-runners and other people from the surrounding rural communities.

Shooting wild horses, Samuel Calvert, 1889.

State Library of Victoria

In many places rangers were and are intimately part of the community, not seen as “public servants”. There is a complex and interesting relationship between university-educated national parks staff and local rural workers with deeply embodied knowledge and skills, with rangers acknowledging that they need the skills of these locals to carry out much animal-related work in the parks, including trapping and mustering wild horses. Recent proposals to helicopter shoot large numbers of wild horses in Kosciuszko would potentially sever this link. Helicopter shooting requires specific marksmanship skills not common in rural communities.

While we debate how to reduce our wild horse numbers, other countries are working to re-establish wild horse herds in Europe and Asia. It is often argued that domestication saved horses (and many other species) from extinction, aiding their establishment all over the planet while their wild ancestors diminished or disappeared. Creating populations of newly wild species is termed both “rewilding’ and ”de-domestication“, and there are numerous and increasing examples around the world. Some of these proposals include the reestablishment of species long extinct, or their ecological equivalents.

In the period increasingly accepted as the Anthropocene, species are both declining and flourishing. Domesticated species have been moved all over the world; other introduced species flourish in new landscapes, and many of these are escaped or released domesticates. In the oceans, as large predators have declined all the cephalopods (octopus, squid and cuttlefish) are increasing. Highly specialised species that evolved on isolated islands have declined precipitously, while generalist species are flourishing.

Global conservation management attempts to work against both of these trends: we attempt to suppress populations of flourishing species, while supporting or increasing populations of declining ones, including through translocations and captive breeding programs. These activities call into question the nature of nature in the 21st century: what is the "wild” in all this management and manipulation?

Shooting wild horses, Samuel Calvert, 1889.

State Library of Victoria

In many places rangers were and are intimately part of the community, not seen as “public servants”. There is a complex and interesting relationship between university-educated national parks staff and local rural workers with deeply embodied knowledge and skills, with rangers acknowledging that they need the skills of these locals to carry out much animal-related work in the parks, including trapping and mustering wild horses. Recent proposals to helicopter shoot large numbers of wild horses in Kosciuszko would potentially sever this link. Helicopter shooting requires specific marksmanship skills not common in rural communities.

While we debate how to reduce our wild horse numbers, other countries are working to re-establish wild horse herds in Europe and Asia. It is often argued that domestication saved horses (and many other species) from extinction, aiding their establishment all over the planet while their wild ancestors diminished or disappeared. Creating populations of newly wild species is termed both “rewilding’ and ”de-domestication“, and there are numerous and increasing examples around the world. Some of these proposals include the reestablishment of species long extinct, or their ecological equivalents.

In the period increasingly accepted as the Anthropocene, species are both declining and flourishing. Domesticated species have been moved all over the world; other introduced species flourish in new landscapes, and many of these are escaped or released domesticates. In the oceans, as large predators have declined all the cephalopods (octopus, squid and cuttlefish) are increasing. Highly specialised species that evolved on isolated islands have declined precipitously, while generalist species are flourishing.

Global conservation management attempts to work against both of these trends: we attempt to suppress populations of flourishing species, while supporting or increasing populations of declining ones, including through translocations and captive breeding programs. These activities call into question the nature of nature in the 21st century: what is the "wild” in all this management and manipulation?

While Australia debates removing wild horses, other countries are seeking to increase their wild herds.

Shutterstock.com

In these questions, the lives and cosmologies of Indigenous peoples, and the lives of other species, offer us serious teachings. The agency and intelligence of animals, the increasing discoveries of distinct cultures amongst animal populations, the agency of planetary systems in continually reorganising around changing inputs, all stand against the modern human insistence on control, stability and stasis.

While hiking mountain grasslands looking for wild horse bands, I have several times come across horse skeletons whitening in the sunlight, their energy and power transmuted back into the source from which new lives will spring. In a world where human societies are increasingly narcissistic, where our dominant concern is ourselves, recognising the agency and intelligence of other species can be deeply humbling.

Perhaps our task is to harmonise ourselves with these old and new environments, not continually attempt to “manage” them into some other state that we in our hubris think is more desirable, whether ecologically, economically or culturally.

Thanks to Adrienne Corradini, Jen Owens, Blaire Carlon and Tonia Gray for improving my understanding of horse and brumby issues.

While Australia debates removing wild horses, other countries are seeking to increase their wild herds.

Shutterstock.com

In these questions, the lives and cosmologies of Indigenous peoples, and the lives of other species, offer us serious teachings. The agency and intelligence of animals, the increasing discoveries of distinct cultures amongst animal populations, the agency of planetary systems in continually reorganising around changing inputs, all stand against the modern human insistence on control, stability and stasis.

While hiking mountain grasslands looking for wild horse bands, I have several times come across horse skeletons whitening in the sunlight, their energy and power transmuted back into the source from which new lives will spring. In a world where human societies are increasingly narcissistic, where our dominant concern is ourselves, recognising the agency and intelligence of other species can be deeply humbling.

Perhaps our task is to harmonise ourselves with these old and new environments, not continually attempt to “manage” them into some other state that we in our hubris think is more desirable, whether ecologically, economically or culturally.

Thanks to Adrienne Corradini, Jen Owens, Blaire Carlon and Tonia Gray for improving my understanding of horse and brumby issues.

Authors: Michael Adams, Associate Professor of Human Geography, University of Wollongong

Read more http://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-cultural-meanings-of-wild-horses-84198