Do trauma victims really repress memories and can therapy induce false memories?

- Written by Louise Newman, Director of the Centre for Women’s Mental Health at the Royal Women’s Hospital and Professor of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne

The Australian newspaper recently reported the royal commission investigating institutional child sex abuse was advocating psychologists use “potentially dangerous” therapy techniques to recover repressed memories in clients with history of trauma. The reports suggest researchers and doctors are speaking out against such practices, which risk implanting false memories in the minds of victims.

The debate about the nature of early trauma memories and their recovery isn’t new. Since Sigmund Freud developed the idea of “repression” – where people store away memories of stressful childhood events so they don’t interfere with daily life – psychologists and law practitioners have been arguing about the nature of memory and whether it’s possible to create false memories of past situations.

Recovery from trauma for some people involves recalling and understanding past events. But repressed memories, where the victim remembers nothing of the abuse, are relatively uncommon and there is little reliable evidence about their frequency in trauma survivors. According to reports from clinical practice and experimental studies of recall, most patients can partially recall events, even if elements of these have been suppressed.

What are repressed memories?

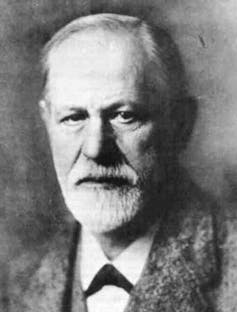

Sigmund Freud introduced the concept of child abuse underlying disorders such as hysteria.

Wikimedia Commons

Sigmund Freud introduced the concept of child abuse underlying disorders such as hysteria.

Wikimedia Commons

Freud introduced the concept that child abuse is a major cause of mental disorders such as hysteria, also known as conversion disorder. People with these disorders could lose bodily functions, such as the ability to move one of their limbs, following a stressful event.

The concept of repressing traumatic memories was part of this model. Repression, as Freud saw it, is a fundamental defensive process where the mind forgets or places events, thoughts and memories we cannot acknowledge or bear elsewhere.

Freud also suggested that if these memories weren’t recalled, it could result in physical or mental symptoms. He argued symptoms of a mental disorder can be a return of the repressed memories, or a symbolic way of communicating a traumatic event. An example would be suddenly losing speech ability when someone has a terrible memory of trauma they feel unable to disclose.

This idea of hidden traumas and their ability to influence psychological functioning despite not being recalled or available to consciousness has shaped much of our current thinking about symptoms and the need to understand what lies behind them.

Those who accept the repression interpretation argue children may repress memories of early abuse for many years and that these can be recalled when it’s safe to do so. This is variously referred to as traumatic amnesia or dissociative amnesia. Proponents accept repressed traumatic memories can be accurate and used in therapy to recover memories and build up an account of early experiences.

Read more: Dissociative identity disorder exists and is the result of childhood trauma

False memory and the memory wars

Freud later withdrew his initial ideas around abuse underlying mental health disorders. He instead drew on his belief of the child’s commonly held sexual fantasies about their parents, which he said could influence formation of memories that did not did not mean actual sexual behaviour had taken place. This may have been Freud caving in to the social pressures of his time.

This interpretation lent itself to the false memory hypothesis. Here the argument is that memory can be distorted, sometimes even by therapists. This can influence the experience of recalling memories, resulting in false memories.

Those who hold this view oppose therapy approaches based on uncovering memories and believe it’s better to focus on recovery from current symptoms related to trauma. This group point out that emotionally traumatic memory can be more vividly remembered than non-traumatic memories, so it wouldn’t hold these events would be repressed. They remain sceptical about reclaimed memories and even more so about therapies based on recall – such as recovered memory therapy and hypnosis.

The false memory hypothesis holds memories can be distorted.

Mark Bonica/Flickr, CC BY

The false memory hypothesis holds memories can be distorted.

Mark Bonica/Flickr, CC BY

The 1990s saw the height of these memory wars, as they came to be known, between proponents of repressed memory and those of the false memory hypothesis. The debate was influenced by increasing awareness and research on memory systems in academic psychology and an attitude of scepticism about therapeutic approaches focused on encouraging recall of past trauma.

In 1992, the parents of Jennifer Freyd, who had accused her father of sexual assault, founded the False Memory Syndrome Foundation. The parents maintained Jennifer’s accusations were false and encouraged by recovered memory therapy. While the foundation has claimed false memories of abuse are easily created by therapies of dubious validity, there is no good evidence of a “false memory syndrome” that can be reliably defined, or any evidence of how widespread the use of these types of therapies might be.

An unhelpful debate

Both sides do agree that abuse and trauma during critical developmental periods are related to both biological and psychological vulnerability. Early trauma creates physical changes in the brain that predispose the individual to mental disorders in later life. Early trauma has a negative impact on self-esteem and the ability to form trusting relationships. The consequences can be lifelong.

A therapist’s role is to help abuse survivors deal with these long-term consequences and gain better control of their emotional life and interpersonal functioning. Some survivors will want to have relief from ongoing symptoms of anxiety, memories of abuse and experiences such as nightmares.

Others may express the need for a greater understanding of their experiences and to be free from feelings of self-blame and guilt they may have carried from childhood. Some individuals will benefit from longer psychotherapies dealing with the impact of child abuse on their lives.

Most therapists use techniques such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy, which aren’t aimed exclusively at recovering memories of abuse. The royal commission has heard evidence of the serious impact of being dismissed or not believed when making disclosures of abuse and seeking protection. The therapist should be respectful and guided by the needs of the survivor.

Read more: Why does it take victims of child sex abuse so long to speak up?

Right now, we need to acknowledge child abuse on a large scale and develop approaches for intervention. It may be time to move beyond these memory wars and focus on the impacts of abuse on victims; impacts greater than the direct symptoms of trauma.

It’s vital psychotherapy acknowledges the variation in responses to trauma and the profound impact of betrayal in abusive families. Repetition of invalidation and denial should be avoided in academic debate and clinical approaches.

Authors: Louise Newman, Director of the Centre for Women’s Mental Health at the Royal Women’s Hospital and Professor of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne