The Great Australian Plays: Williamson, Hibberd and the better angels of our country's nature

- Written by Julian Meyrick, Professor of Creative Arts, Flinders University

Two of Australian theatre’s most celebrated artists are scientists. Their CVs may not be immediately recognizable. One is an engineer, an ex-thermodynamics lecturer, and holds a Masters degree in social psychology. The other is a medical doctor, a onetime hospital registrar, and a specialist in clinical immunology.

Between them they have written nearly 100 plays, some among the best known and most successful of the last 50 years. Both were born in the 1940s in regional Victoria, one in Bairnsdale, the other in Warracknabeal. Both were members of the legendary New Wave theatre company, the Australian Performing Group, otherwise known as the Pram Factory. Both are unusually tall.

They are David Williamson and Jack Hibberd. In pairing them, I am not suggesting they are worth only half an article each, only that existing coverage of their work means they can be touched on more lightly here.

They tower over Australian drama metaphorically as well as literally, and it is impossible to do justice to the depth, scope and variety of their writing in a short piece, however adroit.

Instead, I will look at just two plays - Williamson’s The Department (1976) and Hibberd’s A Stretch of the Imagination (1972) - comparing them in ways that point up the main features of their signal talents. What unites the two writers is the strange yet compelling detachment of their visions. In becoming artists they remained scientists, and it is partly their remarkable powers of observation – of biological processes, social hierarchies and psychological states of mind – that imbues their drama with its impressive stage presence.

Schemers and squid piss

The Department is set in the engineering department of a Melbourne tertiary college. It’s more CAE than university, but is stocked by the same samples of flawed humanity who comprise the staff of any teaching institution.

The characters and themes are classic Williamson territory: male egos in bruising competition. The head lecturer is the middle-aged Robby, whose serpentine cunning and endless scheming is matched only by an altruistic determination to keep his wayward colleagues together. He wheedles, bullies and manipulates. He also confides, reassures and protects. He is, in short, a complicated and absorbing human being and a fitting subject for Williamson’s dispassionate gaze.

Max Gillies as Monk O’Neill in the 1976 APG Production of A Stretch of the Imagination.

Photo: Brendan Hennessy

Max Gillies as Monk O’Neill in the 1976 APG Production of A Stretch of the Imagination.

Photo: Brendan Hennessy

A Stretch of the Imagination, by contrast, is a play with just one character in it, Monk O’Neill, and a setting devoid of feature and variety. Somewhere in the outback, probably, where the sun sears the skin in summer, and the wind cuts to the bone in winter.

Monk is old and waiting to die. All around him are signs of decay, and his body is breaking down even as his mind retreats into the past. Yet, like Robby, he emits an impure energy, an animal spirit, that will not be denied or snuffed out. The links with Waiting for Godot and Happy Days are obvious. But Hibberd’s Monk is the opposite of Beckett’s anti-heroes, wanly juggling disillusion and despair. He is full of life, and a feral buoyancy that cocks a snoot at European Weltschmertz. Here he is delivering one of his typical old-coot reminiscences:

To imagine that as a young man I dined at the most select restaurants in Melbourne. A youth of breed and starch – dapper, punctilious, well-kidneyed, etiquette itself. Knew the wines too. Must have an 1876 Chateau Carbonnieux with the basted salamander, anything else would be unspeakably yan yean, eh Jeremy?

(MONK laughs)

Waiter! (Annoyed). Tongs, please! Pluck that slug from the endive. Thank you, Boris. Oh, could you impeach a less bumptious volume from the fiddler this evening? Now, for the mains may I in all impudence suggest you plumb for the hot Shlong Arabesque a la Crème, set off by a Bourdeaux. (Consulting a vast wine list) Mmmm, cellar’s not what it was once, I think 1871, ah oui, the Chateau Pichon-Longuevill-Lalande…

Garcon! This table napkin is much too stiff. Another. It must adapt to the undulations of the lap, not rasp and chafe the Savile Row, you ox. For dessert, mes amis, it is impossible to eschew the Acheron Meringue, an ingenuous local confection in the shape of a coffin. You call that coffee, cameriere, it’s squid piss! Summon the manager. At least the saxophonist is in tune.

Hibberd’s love of language irradiates Stretch of the Imagination, making it a paean to Australian-English, that mongrel repository of historical terms, regional slang and purloined native words. Like many people with nothing to do, Monk is a talker. As he wiles away his days, he dishes up a succession of tall tales that nevertheless feel true to character: to a man who’s seen a bit, done a bit, and stuffed up a lot.

By comparison, the language of The Department is merely serviceable. It does not contain the puns, allusions, alliterative brilliancies and spiraling absurdities of Hibberd’s masterpiece. But then it does not need to. At the centre of the stage setting is a fuel-injected Ruston diesel engine. It is a metaphor for the play overall. Williamson’s drama is propelled, piston-like, by its storyline. Where Stretch idles and marks time, The Department surges forward through a succession of reveals and reversals that would have Aristotle applauding at the skill of a master narrator (Williamson would later be dubbed “storyteller to his tribe”).

The rite of the committee meeting

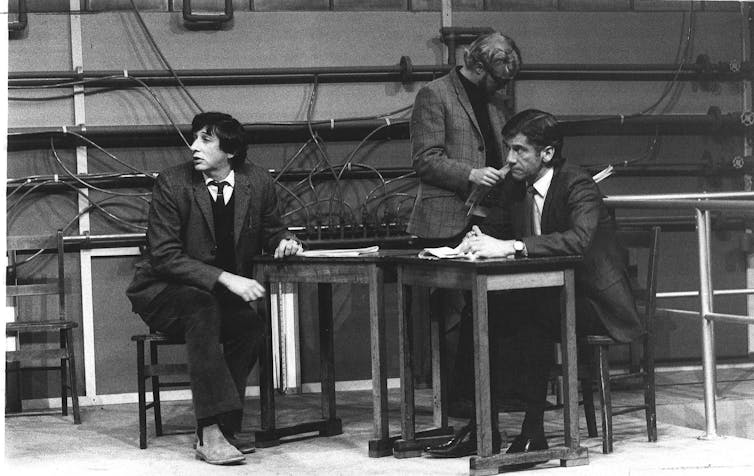

George Szewcow as John, Patrick Frost as Peter and Leslie Dayman as Hans in a SATC production of The Department at Parade Theatre, Sydney, 1975.

Photo: Grant Matthews

The action of The Department involves an archetypal 20th century rite, the committee meeting. In his element, Robby flattens, flatters, threatens and rewards the vainglorious, ratbag crew around him. He must achieve all his goals, chief of which is that all his goals must be achieved. Whether the issue is significant or trivial, relevant or tangential, rational or barking mad, Robbie’s iron will has to prevail. Here’s the committee talking about something that often invokes strong feelings: designated lavatories.

George Szewcow as John, Patrick Frost as Peter and Leslie Dayman as Hans in a SATC production of The Department at Parade Theatre, Sydney, 1975.

Photo: Grant Matthews

The action of The Department involves an archetypal 20th century rite, the committee meeting. In his element, Robby flattens, flatters, threatens and rewards the vainglorious, ratbag crew around him. He must achieve all his goals, chief of which is that all his goals must be achieved. Whether the issue is significant or trivial, relevant or tangential, rational or barking mad, Robbie’s iron will has to prevail. Here’s the committee talking about something that often invokes strong feelings: designated lavatories.

ROBBY: Misuse of staff amenities. Al’s brought to my attention a rather annoying practice that we’ll have to do something about… How many of you have come across students in staff toilets?

OWEN: I was going to mention that myself.

ROBBY: It’s happened to you?

OWEN: A couple of times in the last few weeks. It’s very embarrassing too. You get annoyed but you’d feel stupid if you ordered them out.

BOBBY: I’ve noticed it a couple of times.

PETER: Does it really matter?

AL: They’ve got their own toilets.

BOBBY: And they’re much bigger than ours.

JOHN: Ours is more tasteful.

BOBBY: I think we should treat this seriously, John.

MYRA: I can’t believe it.

PETER: No, Myra. You don’t understand. When men stand up at a urinal an element of competitiveness creeps into it. If a fellow staff member has the drop on you that’s bad enough, but if a students beats you that’s humiliating.

HANS: It’s worse now that Neigus has broken his wrist. You’ve got to unzip his fly for him.

BOBBY: Neigus came in while I was there and I dried right up. Sorry, Myra.

In view of the fact that Williamson is sometimes criticized for writing weak or stereotypical women, it is interesting to note that in this consummately male-energy play, the character of Myra stands out in beautifully balanced relief. Myra is a visiting Humanities lecturer, teaching engineering students optional history.

She is amazed, appalled and amused at the antics around her, and by Robby’s endless vitality. She’s attracted to him, and possibly he to her. But nothing will happen because Robby is already married – to the Department. Their stillborn relationship is woven into the fringes of the action; another deft piece of playwriting.

In Stretch, Monk O’Neill is going nowhere, his yarns designed to fill the empty hours. Yet the consciousness of the play overall – if plays can be said to have a consciousness, and I think they can – is of the most fateful kind: the meaning of life, the inevitability of death.

By contrast, Robby and his staff are manically purposeful, clambering over each other in a lather of personal ambition and rivalry. But the results of their competitive behaviour seems oddly nugatory, just an excuse for the struggle itself – the will to dominate, to come out on top.

Indolence and energy

Thus Stretch’s indolence and The Department’s energy reverse back on themselves and illuminate opposite qualities. There is a case study feel to both plays, as if Hibberd and Williamson were engaged in experiments: scientists still, as well as artists.

Neil Fitzpatrick as Robby in the SATC production of The Department.

Photo: Robert Walker

Neil Fitzpatrick as Robby in the SATC production of The Department.

Photo: Robert Walker

In my third article for this series, I suggested that Australian drama is driven (and riven) by two stylistic impulses: an emotionally satisfying realism, and an intellectually-challenging anti-realism. It is not hard to see Williamson as the naturalistic inheritor of Ray Lawler and Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Hibberd as the expressionistic legatee of Patrick White and A Cheery Soul.

But genre-based classifications are not fair to either writer, nor do they explain the power of their plays. There are elements of The Department that are surreal: the towing tank the staff dare not fill with water lest the building around it collapse (they do fill it, and the building does not collapse). And there are aspects of Stretch that portray naturalistic detail, like the state of Monk’s physical health, and his real guilt for real misdeeds behind his elaborate fancifications.

Better to see the two plays as managing the realism/anti-realism binary as an internal tension. Indeed it is their capacity to do this – to occupy two dramatic registers at the same time – that makes them outstanding works. It also lends them a shared tone hard to describe. Larrikin, perhaps. A raucous, godless, large-hearted empathy. A polyglot creativity wherein no joke is too low to deliver, no feeling too outrageous to admit, no thought too weird to expound.

I was in my twenties when I first came across the work of Williamson, Hibberd and other Pram playwrights. I had by then read hundreds of plays, mostly of British and US origin. I had never come across anything quite like theirs.

They are distinct. And if the question is asked “how are they distinct?” I’m not sure I could give a clear answer, except to say that in some fundamental but non-Pauline Hanson way, they express the unique contours of our national imagination.

So it seemed to me then, and so it seems to me now. Stretch of the Imagination and The Department breathe with an originality and an ill-mannered yet liberating intelligence that reflects the better angels of Australia’s nature.

Authors: Julian Meyrick, Professor of Creative Arts, Flinders University