The pathologies of populism

- Written by John Keane, Professor of Politics, University of Sydney

During the past year, The Conversation and the Sydney Democracy Network, a global partnership of researchers, journalists, activists, policymakers and citizens concerned with the future of democracy, have published a lengthy series of scholarly reflections on the causes and consequences of populism.

The following remarks aim to summarise the contributions, to tease out their insights, and to draw some conclusions about the vexed relationship between populism and democracy.

Many people are today asking questions about the worldwide upsurge of populism. Does burgeoning talk of “the people”, and action by governments in their name, offer fresh hopes for democrats in these darkening times? Can populism rescue us from the corruption and decay of the ideals and institutions of monitory democracy, now under attack from a potent variety of corrosive and contradictory forces?

Are Nigel Farage and other peddlers of populism basically right when colourfully they call upon a “people’s army” to take back “their country” by sparking a “political tsunami” in support of “democracy” against a corrupted “political class”?

The spirit of populism

In a sign of our times, the two dozen contributors to this series on populism, and democrats everywhere, are divided deeply in their replies to such questions, and about what can and should be done to deal with the upsurge of populism.

Without doubt, most democratically minded scholars, journalists and commentators find the new populism fascinating. For several years, hypnotised by its “simple, headline-grabbing, dramatic message” (Benjamin Moffitt), populism has been their favourite topic of discussion.

Some are genuinely unsure about what to think, or what to do. They prevaricate: sit on the fence or, as Simon Tormey proposes in his interpretation of populism as the pharmákon of democracy, keep their minds open to the perplexing dialectics and potentially surprising, if unintended, practical effects of populist politics.

These abreactions are understandable, not least because populism is a political phenomenon marked by democratic qualities. What could be more democratic than public attacks on financial and governing oligarchs, “unrepresentative plutocracies” (Christine Milne), in the name of a sovereign people? Isn’t democracy after all a way of life founded on the authority of “the people”?

And what about the populist account of the pathologies of contemporary parliamentary democracy? When measured in terms of political “theatrics” (Mark Chou), populism is “a spectre of things to come: of political performance in an age of projection rather than representation” (Stephen Coleman).

Jan Zielonka notes that within today’s so-called democracies far too many governments regard themselves as “a kind of enlightened administration on behalf of an ignorant public”. Ulrike Guérot says that in an age when “nobody seems to care” and “opportunity remains a fiction for many people”, we should not be surprised by the global upsurge of populism.

Wolfgang Merkel agrees. He describes contemporary populism as a “rebellion of the disenfranchised” and a symptom of the “general failure of the moderate left to address the distributive question”.

They and other contributors warn that the diagnoses proffered by Rodrigo Duterte, Thaksin Shinawatra, Narendra Modi, Marine Le Pen and other populists contain more than a few grains of truth.

In effect, all contributors to this series ask: isn’t the populist mobilisation of public hope, its insistence that things can be different and that people should expect better, consonant with the spirit of democracy and its equality principle?

The Life and Death of Democracy, my contribution to rethinking the history of democracy’s spirit, language and institutions, replies to these questions by analysing populism as a recurrent autoimmune disease of democracy.

That’s to say populism is not just a symptom of the failure of democratic institutions to respond effectively to anti-democratic challenges such as the “growing influence of unelected bodies” (Cristóbal Kaltwasser), rising inequality and the dark money poisoning of elections; populism is itself a problematic and perverted response that inflames and damages the cells, tissues and organs of democratic institutions.

The point should be obvious, but it’s often ignored: populism is a pseudo-democratic style of politics. In the name of an imagined “people” defined as if it were a demiurge, something akin to a metaphysical gift to earthlings from the gods, populism is a style of politics whose “inner logic” or “spirit” (Montesquieu) destroys power-sharing democracy committed to the principle of equality.

Yes, populism can have positive unintended consequences, as history shows. By publicly exposing the Trump-style crudeness and potential brutality of unbridled state power exercised in the name of “the people”, populism can spark long-lasting democratic reforms. But everywhere, at all times, the inner logic of populist politics and its “folksy slogans” (Takashi Inoguchi) are anything but folksy: their practical effect is to rob life from power-sharing democracy.

Populism “always tends towards extreme forms of plebeianism”, observes our Chinese contributor Yu Keping. He is right. Populism necessitates demagogic leadership. It encourages attacks on independent media, expertise, rule-of-law judiciaries and other power-monitoring institutions.

Populism “denies the pluralism of contemporary societies” (Jan-Werner Müller). It promotes hostility to “enemies” and flirts with violence. It is generally gripped by a territorial mentality that prioritises borders and nation states against “foreigners” and “foreign” influences, including multilateral institutions and so-called “globalisation”.

My line of interpretation may seem harsh, or one-sided, but its feet are planted firmly on the ground. Not only does it pay attention to the inner dynamics (let’s call them) or functional imperatives of populism, it also taps evidence from many recorded cases of populism, past and present. T

he interpretation notes that populism is a recurrent feature of the history of democracy, and it pinpoints the efforts by past democrats to cure the democratic disease of populism.

Ostraka cast against Aristides, Themistocles, Cimon and Pericles, Athens, 5th century BCE.

John Keane

Ostraka cast against Aristides, Themistocles, Cimon and Pericles, Athens, 5th century BCE.

John Keane

In the age of assembly democracy, for instance, citizens of Athens and other city-based democracies dealt with demagogues by voting to send them into prolonged exile, a practice known as ostrakismos .

During the early modern age of representative democracy, by contrast, periodic elections, multi-party systems and parliamentary government in constitutional form were designed to check and restrain populist outbursts (“the people”, noted John Stuart Mill in On Liberty, “may desire to oppress a part of their number” so that “precautions are as much needed against this as against any other abuse of power”).

Our post-1945 age of monitory democracy was born of efforts to apply much tougher political restrictions to (fascist and other totalitarian) abuses of power in the name of a fictive people.

Public integrity bodies, human rights commissions, activist courts, participatory budgeting, teach-ins, digital media gate watching, global whistle-blowing, bio-regional assemblies: these and scores of other innovations were designed to check populists bent on self-aggrandisement in the name of “the people”.

Current events show that this old problem of populism is making a comeback, and that populism is indeed an autoimmune disease of monitory democracy. Populism picks fights with key monitory institutions, such as the courts, “experts”, “fake news” platforms and other media “presstitutes” (Modi). The new populism wants to turn back the clock to simpler times when (it imagines) democracy meant “the people” were in charge of those who ruled over them.

Political dynamics in Hungary, the US, Poland, Thailand and elsewhere show that the aim of the new populism is to amass a fund of power for itself and its influential supporters. That’s why it is bent on destroying as many power-monitoring, power-restraining mechanisms as it can, in quick time, all in the name of a people that is never carefully defined, a phantom people that is simultaneously present and absent, everything and nothing.

Left populism?

How serious is the populist threat to monitory democracy?

More than a few democrats, especially those with a strong sense of history, suppose that the current epidemic of populism will abate. They think along the lines sketched by the American historian Richard Hofstadter, who once likened populism to a stinging bee. After causing annoyance and inflicting pain in the backside of the political establishment, populism, on this view, typically dies a slow death, especially after it reaches elected office.

Workingmen’s Party of California 1870s postcard.

Boston Public Library

Workingmen’s Party of California 1870s postcard.

Boston Public Library

Hofstadter was principally concerned with the American case, where during the late 19th-century populist parties such as the Workingmen’s Party of California and the Populist Party were outflanked using democratic means, cleverly and constructively transformed by their elected opponents into catalysts of long-lasting democratic reforms.

As Michael Kazin and others have noted, the dialectics of populism produced surprising results. While at first populist bigotry prevailed (“The Chinese Must Go!” campaign in California, for instance), populist politics, in spite of its exclusionary impulses, helped trigger such inclusive democratic reforms as the full enfranchisement of women (1920), a directly elected Senate (1913), municipal socialism, new laws covering income tax and corporate regulation and the eight-hour working day for all wage earners in the country.

More than a few analysts and defenders of democracy are today tempted to think in this way about the tactical outflanking of populism.

Earlier this year, for instance, American political scientist Larry Diamond told the BBC that “mainstream politicians” will need to concede ground, stepping back from their previous “liberal” commitments to open-door immigration and global trade. The overriding aim must be to defeat populist “authoritarianism” by absorbing its concerns into mainstream “liberal democratic” politics.

Diamond cited the example of Geert Wilders, whose populist PVV (Party for Freedom) in the Netherlands did worse than expected in recent elections exactly because Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte grasped what was happening and reacted by making “significant policy adjustments”.

It’s worth noting that among these concessions was Rutte’s public announcement that the Dutch experiment with “multiculturalism” was over. Many Dutch citizens were shocked, not just by the indignity inflicted verbally on various minorities, but by the realisation that Rutte hadn’t prevailed over the populist right, but joined its ranks.

Making political concessions to populists is risky business. It can result in co-optation and end in charges of hypocrisy, outright political humiliation and defeat. That is why, historians remind us, the power ambitions of populism were sometimes blocked by their opponents using more drastic means, as in late 19th-century Russia. There its public appeal was snuffed out anti-democratically, killed by armed force.

Elected populist governments also tasted forcible overthrow by coup d'état. This was the fate of El Conductor, Juan Domingo Perón. The former Argentine lieutenant-general and twice-elected president was forced from office into exile (in September 1955), hunted by hostile allegations of demagogic corruption and dictatorship. These were charges designed to erase forever memories of his massive support by millions of Argentine citizens, his many descamisados (“shirtless”) followers rapt by his efforts to dignify labour and eradicate poverty.

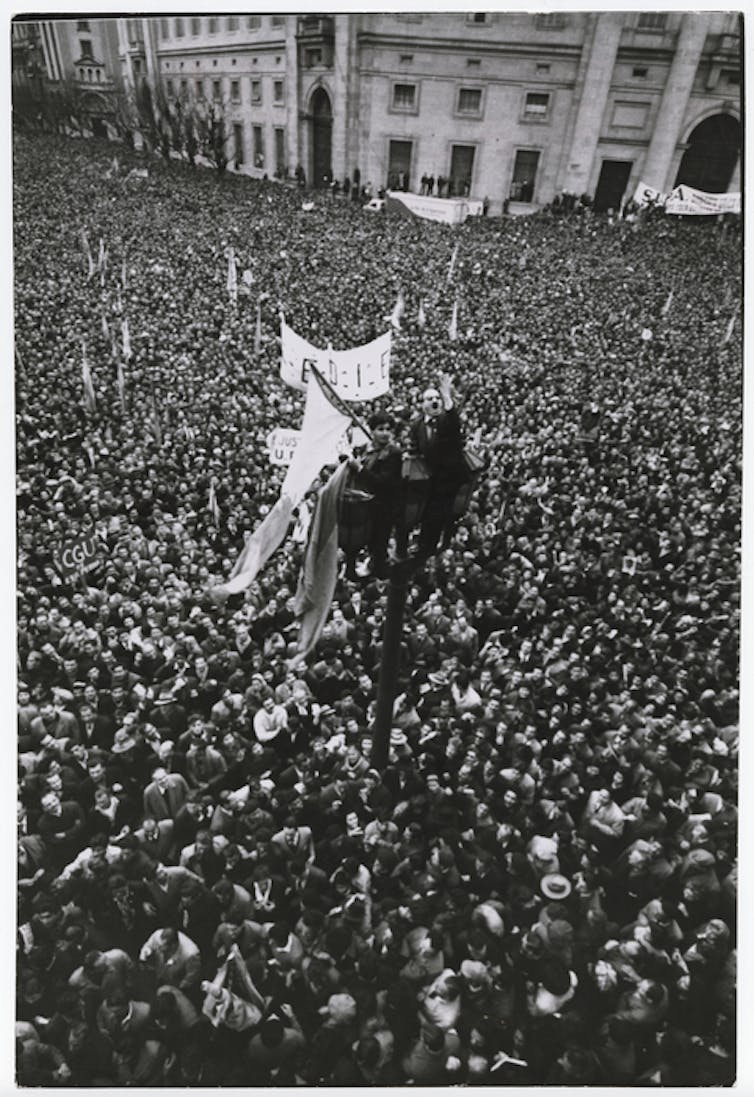

Supporters of Juan Perón perch atop a lamp post at a rally in Buenos Aires in the 1950s.

Cornell Capa/International Center of Photography

Supporters of Juan Perón perch atop a lamp post at a rally in Buenos Aires in the 1950s.

Cornell Capa/International Center of Photography

Inspired by the example of Perón, the Belgian scholar Chantal Mouffe is sure there’s another way of meeting the challenge of Trump- and Wilders-style populism: a new, true politics that can get us out from under the rubble of collapsing “liberal democratic” institutions.

Known globally for her thinking and writing on politics and popular sovereignty, Mouffe calls for a new brand of “left-wing populism”.

During the past year, and in an earlier contribution to this series, she has launched spirited attacks on what she calls the “anti-populist hysteria” of our time.

She’s also sided publicly with populist leaders like Jean-Luc Mélenchon. He’s the politician who in June stood on the steps of the Assemblée Nationale, together with his newly elected La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) MPs, fists clenched, laced with shouts of “Resistance!” and his talk of their collective “service of the people”.

Mouffe’s political thinking is symptomatic of a rise of aesthetic and political fascination among disaffected left-of-centre intellectuals with populism.

The attraction is understandable. It has a positive side. It embraces the “wisdoms” of contemporary populism: for instance, the ways in which contemporary populists have exposed the “deep tension between democracy and capitalism” (Thamy Pogrebinschi), turned their backs on corrupted middle-of-the-road cartel parties, denounced rising social inequality, poured scorn on the deadening breaking news “churnalism” of mainstream media platforms and raised expectations among millions of people that things can and must be better.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon in action.

Alain Jocard/Reuters

Jean-Luc Mélenchon in action.

Alain Jocard/Reuters

Mouffe echoes these points, but her principal contention, in opposition to “neoliberalism”, is that the political right enjoys no monopoly on populism. A left-wing populism is possible and is needed urgently in these anti-democratic times. She concludes that “the only way to counter right-wing populism is through left-wing populism”.

The argument is expressed in simple binary terms. But what exactly does she mean, in theory and practice?

Mouffe’s reply runs thus: the imperative is to defend and extend “democracy”, understood as a political form that draws strength from “the power of the people”.

So understood, democracy is “ultimately irreconcilable” with, and superior to, “political liberalism” and its mantras of the rule of law, the separation of powers, free markets and the defence of the individual. A commitment to democracy implies opposition to “post-politics”, the liberal and neoliberal “blurring of [the] frontier” between the right and the left.

Mouffe explains the recommendation at greater length in On the Political and deploys it in her latest pleas for more democracy and support for Mélenchon. The “principles of popular sovereignty and equality”, she writes, “are constitutive of democratic politics”. So what is now needed, and what she predicts will have to be born, is left-wing populism, an “agonistic populism” that breaks with exhausted “social democracy”.

The point is to stop philosophising and to begin drawing lines by means of a new politics (the language is obviously drawn from Marx and Engels and Gramsci) that “divides society into two camps” by engaging in a “war of position”, in support of the “underdog” against “those in power”.

How are we to assess these large claims? Her thesis certainly invites historical objections.

I have noted elsewhere that Mouffe’s reliance on Carl Schmitt’s attack on liberalism misleads her into saying that “the origin of parliamentary democracy”, the watering down of democracy by liberal representative government, resulted from the 19th-century marriage of convenience of “political liberalism” and “democracy”.

In her own defence, Mouffe cites my doctoral supervisor, C.B. Macpherson, but this was not exactly his argument (his vision of future democracy preserved plenty of liberal themes, for instance).

Besides, as The Life and Death of Democracy shows in some detail, parliamentary representation has pre-liberal medieval roots, while the republican melding of the languages and institutions of representation and democracy happened during the last quarter of the 18th century, not in the century that followed.

These are fripperies over which historians and political thinkers bicker and tussle. They needn’t detain us. The real trouble is with Mouffe’s case for “left-wing populism”.

My discomfort stems not only from its poor sense of the history of democracy, her wilful ignorance about monitory democracy and her unjustified nostalgia for an unadulterated “sovereign people” principle.

Or from the fact that her rhetorical style is Bolshevik, a species of “redemptive” political thinking that preaches the need for “agonistic” (pain-in-the-backside) populism and the use of “democratic means” to “fight” with “passions” against “an adversary” (which passions? which adversary?, she doesn’t say).

Or discomfort triggered by the suspicion that her commitment to “democratic Hobbesian” axioms is worse than oxymoronic, but actually self-contradictory.

Mouffe reduces democracy to a mere tactical weapon. It is a means for dealing agonistically with enemies.

In her view, democracy courts violent power conflicts, in accordance with the old Hobbes principle of homo homini lupus (man a wolf to men), the precept that warns that politics is about the danger that the world can lurch towards an unruly “state of nature”, in which (so much for the sovereign people principle!) actual human life becomes solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.

It’s true there are fleeting moments when Mouffe’s vision of left-wing populism admits of the dangers of “authoritarian populism”. The “antagonistic populism” of the French Revolution is the example she gives, by means of a half-hearted anachronism (the terms populist and populism were coined only in the mid-19th century).

That doesn’t really rescue her overall argument from association with the politically damaging pathologies typically found within every type of populism. These pathologies blindside her whole argument.

What’s more, they are normally ignored in treatments of populism as a “thin-centred ideology” (Cas Mudde) bent on separating any given society into two homogeneous but antagonistic groups: “the corrupt elite” and “the pure people”, whose volonté générale (general will) should be the measure of all things political.

“Depending on its electoral power and the context in which it arises, populism can work as either a threat to or a corrective for democracy,” Mudde and his co-author Cristóbal Kaltwasser write. “This means that populism per se is neither good nor bad for the democratic system.”

In this SDN-commissioned series, Thamy Pogrebinschi echoes the point. She says that since “populism is not an ideology”, it “can be so politically empty that it joins forces with ideologies as different as socialism and nationalism. Populist discourses can thus favour exclusion, or inclusion.”

This content-centred approach, a way of understanding populism as a “thin-centred ideology”, addressing only a limited set of issues and open to variations as different as “nationalism” and “socialism”, is evidently mistaken. It fails to spot the pathologies inherent within all forms of populism.

Pathologies

The most obvious formal pathology is the inner dependence of populism upon political bosses. “It is not a question of ending representative democracy,” says Mouffe, “but of strengthening the institutions that give voice to the people.”

Fine words but, to put things bluntly, this precept wilfully ignores the way populism functionally requires big-mouthed demagogy, a devil’s pact with leaders who pretend to be the earthly avatars of “the people”.

Chavez, Wilders, Fujimori, Trump, Kaczynski and other demagogues are neither incidental nor accidental features of populist politics: metaphysical talk of a people necessitates the personalisation of power.

When seen in populist terms, emancipation of a people can never be the work of The People itself; populism and substitutionism are twins.

Ecuador’s most famous populist Jose Maria Velasco, who was elected president five times but deposed by the army four times, understood this well. “Give me a balcony, and I will become president,” he liked to say.

Sometimes, as Irfan Ahmad points out in his contribution to this series, Big Leader populists claim they have the support of the heavens. Vox princeps, vox populi, vox dei. This is the way Modi interpreted his 2014 electoral victory: as the victory of “the will of the people” blessed by the Hindu god Lord Krishna (janata jan janārdan).

“Left populism” dispenses with talk of deities, but it similarly demands the materialised embodiment of “the people” in a leader capable of mobilising sections of “the people” to confirm who they are: The People.

Populism is demolatry. Populism is ventriloquism. Through acts of concealed representation, it incites and excites Big Leaders who are above the common herd, The Ones who attract a coterie of lesser, loyal people, citizens who are encouraged to follow because they are offered spoils, calculated gifts designed to produce followership from leadership.

Populism so interpreted is a strangely anti-democratic throwback, a 21st-century and secularised version of the old king’s “two bodies” doctrine, which supposed the body of the crowned ruler is the spiritual and visceral manifestation of the body of the people.

In contrast to the “two bodies” doctrine, however, today’s populism has no seamless solution to the succession problem when the Great Leader dies, or is felled, as Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Nicolás Maduro have both been forced to recognise.

The earthly worship of the mortal political boss helps explain other pathologies lurking within Mouffe’s call for a left-wing populism. In this series and in his book, What Is Populism?, Jan-Werner Müller notes the simple-minded mentality of populism, its hostility to ambivalence, complexity and pluralism.

The point needs toughening: the drive to build followers by big boss leaders fuels their hostility to institutions that stand in their way. Populists have little or no taste for institutional give-and-take politics. Unchecked ambition is their thing; so is tactical manoeuvring to deconstruct and simplify organisations and their rules. Populism loves monism.

Gripped by an inner urge to destroy checks, balances and mechanisms for publicly scrutinising and restraining power, populist leaders and parties reveal their true colours in action. It’s a myth that election to office slakes their thirst for power.

In Alberto Fujimori’s Peru, democracia plena (as he called it) meant hostility to the palabrería (excessive, idle talk) of the political class and its established media. Declaring an end to oligarchy, government secrecy and silence, it proceeded to contradict itself by bribing and browbeating legislators, judges, bureaucrats and corporate executives.

Theresa May nowadays dreams of transforming the Westminster parliament into a poodle of executive power, in the name of a fictional “British people”. Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta rails against courts run by “thugs” paid by “foreigners and other fools” who rule “against the will of the people”.

In Hungary, the government of Viktor Orbán has collared mainstream media, the judiciary and the police, and now breathes fire down the necks of the universities and civil society organisations. “We are committed to using all legal means at our disposal to stop pseudo-civil society spy groups such as the ones funded by George Soros,” says Human Capacities Minister Zoltán Balog.

Supporters of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party march through Budapest.

Laszlo Balogh/Reuters

Supporters of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party march through Budapest.

Laszlo Balogh/Reuters

Trump meanwhile seems to be locked in a low-level, permanent war with Congress, so-called fake news media, the judiciary and intelligence services, even the Boy Scouts of America. He hankers after trust in family ties, and demands loyalty from his followers, egged on by their talk of the need to “bring everything crashing down” through deep budget cuts, centralisation of federal decision-making and refusing to fill empty leadership positions.

Trump thinks of himself as a lollapalooza leader who never ever loses. He is thus for government by nepotism: not bureaucracies, but personal channels, self-styled machismo against foes at home and abroad.

None of this clientelismo is accidental, or random: populism yearns for a type of politics that resembles a permanent coup d’état in slow motion. Populism is “not an ideology”, replies Mouffe. “It is a way of doing politics” guided by “the construction of a demos that is constitutive of democracy”.

The reply is tautological, and it begs important questions that lie at the heart of a genuinely democratic politics: in the process of constituting “popular sovereignty”, who decides who gets what, when and how? Who does the politics? Who establishes the “chains of equivalence” to decide who is the demos? Who determines what counts as “democracy”, and how do its champions deal with differences and disagreements about means and ends? Are the champions of “the people” themselves subject to legitimate institutional restraints?

Mouffe provides no clear answers to these political questions. The hush is revealing of her populist understanding of politics as the uncompromising battle to win friends and to monopolise state power over followers persuaded they are the promised People.

The definition of politics is narrowly Hobbesian. Seen as the struggle to win over allies and to crush opponents, populism is a strange and self-harming form of politics.

For tactical reasons, to protect its flanks, populist governments usually forge alliances with friends in high places. For all its talk of empowerment of “the people”, populism embraces the ancient political rule that governments need allies whose loyalty requires that they be treated well.

Populism practises “in-grouping”. Rudiger Dornbusch and other scholars, including James Loxton in this series, have shown that although populism can foster economic growth and redistribute wealth and income in favour of formerly marginalised groups – as in the Bolivia of Eva Morales, the great champion of natural gas-funded public works projects and social programs to fight poverty – it typically has the effect of privileging new sets of elites.

It is well known that Trump’s campaign talk of “draining swamps” is actually filling them with millionaires and billionaires, but left-wing populism doesn’t escape the same rule.

In the name of “the people”, it practically does what all populism does: it creates a wealthy stratum of oligarchs, like Venezuela’s boliburguesía, whose appetite for chartered flights, real estate and luxury cars has been whetted by kickbacks linked to state contracts showered on pro-government corporate executives and former military officials.

The logic of in-grouping inherent in all forms of populism contradicts Mouffe’s claim that left-wing populism is straightforwardly pitted against oligarchy. It confirms the suspicions of ancient Greek democrats, who used a (now obsolete) verb dēmokrateo to describe how demagogues ruling the people in their own name typically team up with rich and powerful aristoi to snuff out democracy.

There’s another self-contradiction that plagues populism. In practice, populism not only cultivates new oligarchs; its struggles in the name of “the people” force it to pick political fights with those it defines as deviants, dissenters and protagonists of disagreement and difference.

Populism champions the tactic of “out-grouping”. That’s why it comes as no surprise that Mouffe’s call for “left-wing populism” is hand-in-glove with Schmitt’s definition of politics as all about “friend-enemy” alliances. We could speak of Mouffe’s Law: “There is no ‘we’ without a ‘they’.”.

At no point does she say who would be excluded from her brand of populism: big business, super-rich bankers, government bureaucrats, confessed neoliberals, surely. But who else, pray tell, would be on her hit list? Knowing perhaps that a detailed list would scare off potential supporters, she doesn’t say.

Still it’s clear that her avowed commitment to “democracy” is contradicted by her dalliance with a politics of exclusion. The contradiction runs deep through populism: in its drive to amass a fund of power, confronted by opponents, populists typically hit hard against those they define as Other.

In the past, the designated enemies were monarchs, aristocrats, railroad magnates, bankers, Chinese immigrants. Today, populists like Wilders rail against Muslims and their “palaces of hatred” and Moroccan youth “street terrorists”. They spit at “liberals” and “foreigners”, unpatriotic people from nowhere, ethnic minorities and environmental activists.

Local politics always defines who exactly is under the gun, but the outcast marginalia of The People are deemed people who are “not even people”.

Writing in this series, Jan-Werner Müller quotes a passing but similarly revealing campaign rally remark by Donald Trump:

The only thing that matters is the unification of the people – because the other people don’t mean anything.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister and populist Yogi Adityanath.

Jitendra Prakash/Reuters

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister and populist Yogi Adityanath.

Jitendra Prakash/Reuters

This way of thinking helps us understand why it is no accident that populists are frequently fascinated by violence, or urge violence, or speak of it as a feature of “human nature”. Some present arms.

Yogi Adityanath, the priest-politician recently appointed as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, says protection of the “rashtra” (nation) is the “dharma” (religion) of his government. Among his favourite personal possessions are a revolver, a rifle and two luxury SUVs, plus a reputation as a much-feared activist who arrives quickly with his supporters at trouble spots, to cause trouble.

By 2014, the pending criminal cases against Adityanath included promoting enmity, attempted murder, defiling a place of worship, trespassing on a burial site and rioting.

Admittedly, this is populism in its most extreme form. But the important thing to see is that the populist commitment to wilful out-grouping of people judged as worthless trash necessarily results in a dalliance with violence. Trump’s advice to police officers, not to be “too nice” when handling suspects, is no exception, no idiosyncrasy.

The dark energy of violence was present at every Trump campaign rally; “knock the crap out of ’em”, “punch ’em in the face” and “carry ’em out on a stretcher” were among his favourite fighting phrases.

Mouffe’s aesthetic fascination with violence fits the same pattern. In a little-known passage, she puts things plainly, in the language of Thomas Hobbes and Carl Schmitt. “The same movement that brings human beings together in their common desire for the same objects,” she writes, “is also at the origin of their antagonisms. Far from being the exterior of exchange, rivalry and violence are therefore its ever-present possibility … violence is ineradicable.”

That conviction is consistent as well with the propensity of Mouffe and other populists to think in territorial terms. They are attached to bounded territorial states. They like borders, stricter visa and immigration rules and talk of “national sovereignty”.

There are times when Mouffe appears to dissent on this point. She says she favours more “democracy” at the European level, but it turns out that her “progressive left-wing populism” comes wrapped within a territorial mentality.

It echoes Mélenchon’s speeches, interviews and policy program, L’Avenir en Commun (A Common Future). This speaks of a “democratic reconstruction” of European treaties and France’s withdrawal from the European Union’s Stability Pact, NATO and the World Bank.

The program also calls for closer ties with Russia and respect for Brexit, without “punishing” the UK for its decision to leave the EU, except for withdrawal from the Le Touquet accord, which allows British border controls to operate inside France.

What’s to be done?

The contributors to this series, for different reasons, are mostly united in their opposition to populism in its various local forms.

Among the exceptions is Adele Webb, whose diagnosis of the public ambivalence produced by dysfunctional democracies sets out mainly to understand the populism of Duterte and Trump, to help us grasp that their popularity stems in no small measure from their “appeal to people’s desire not to be fixed into pre-determined standards of how to think and behave”.

Cristóbal Kaltwasser similarly calls for engaging populists “in honest dialogue” and proposing “solutions to the problems they seek to politicise”. Laurence Whitehead recommends “respectful engagement and genuine dialogue” about the “darker” but potentially “emancipatory” potential of the new populism. Mick Chisnall is interested in interpreting populism as a form of politics based on people’s “identification with a common form of enjoyment-in-transgression”.

Simon Tormey similarly reserves judgement about its political merits. “We have become populists in the sense of seeing elites as disconnected or uncoupled from the people,” he writes.

Populism is symptomatic of the breakdown of representative democracy; but he’s unsure whether populism “will ‘work’ and make life better”, or if “there is life after representative democracy”, or whether the best cure for the dysfunctions of contemporary democracy is a “non- or post-representative strategy that will reduce, if not eliminate, the distance between the people and political power”, for instance through the nurturing of “liquid democracy” and “deliberative assemblies”.

Other contributors, understandably, for good reasons, are more doubtful about the democratic potential of populism; several express open disdain for its pathological, anti-democratic effects.

The anthropologist Irfan Ahmad reminds readers that the Western literature on contemporary populism suffers a secular bias. The case of India shows why the bias is misleading, and why the BJP government led by Modi is spreading a religious form of populism with murderous consequences for Muslims and other non-Hindu citizens.

Henrik Bang, citing Jürgen Habermas, similarly worries about the anti-democratic potential of populism. He reminds us of the political importance of everyday makers, “laypeople who can act spontaneously, emotionally, personally and communicatively as interconnected ‘fire alarms’, ‘experimenters’ and ‘innovators’”.

Bang calls for a new democratic politics that values “mutual acceptance and recognition of difference at all levels, from the personal to the global”, a politics of everyday making that can “push against populism by reminding political authorities that the only exceptional leaders we need today are the ones who help us to govern and take care of ourselves”.

Bang is surely right in questioning the mistaken Mouffe-style presumption that all politics is populist politics.

Along similar lines, using a different language, Nicole Curato and Lucy Parry consider “the democratic virtues of mini-publics” to be a vital antidote to the pathologies of populism.

Populists are said to be the foes of “intellectual rigour”, “evidence” and public-spirited “deliberative reason”. They peddle “base instincts” and “prejudices and misconceptions”. What is needed is more “deliberative democracy”, randomly selected public forums guided by “the virtues of participation governed by reason”.

Their call to rejuvenate the spirit of democracy is laudable. But the proposed vision of “deliberative democracy” suffers a rationalist bias; the means of achieving it are equally questionable.

There is certainly a pressing need in our times for what I have called “a new democratic enlightenment” in which democracy “dreams of itself again”. But the vision of “deliberative democracy” is no match for populism and its pathologies.

Supposing that the “essence of democracy” is “deliberation, as opposed to voting, interest aggregation, constitutional rights, or even self-government” (John S. Dryzek’s opening words in Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations), democracy is reduced to “authentic deliberation”, or “the requirement that communication induce reflection upon preferences in a non-coercive fashion”.

This way of thinking about democracy by deliberative democrats suffers multiple weaknesses. Their self-understanding of their own historicity, and the age of monitory democracy to which they belong, is weak. Their penchant for small-scale, face-to-face deliberative forums begs difficult tactical questions about scalability, including whether micro-level schemes can be replicated at the national, regional and global levels.

Deliberative democrats are prone to understate such strategic challenges as the “artificiality” of pilot scheme experiments (where indefatigable citizen deliberators are expected to behave as if they are rational communicators in a scholarly seminar).

The bullish veto power of power-hungry vested interests is also underestimated. The contested meanings of the word “reason” don’t feature. The propensity of calm “reasonable” talk to dissolve bigoted opinions, of the kind expressed by hardcore populists in “civic dialogues” hosted by Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland to tap rising anxiety about immigration, is exaggerated.

In sum, we could say that the whole vision of “deliberative democracy” suffers from nostalgia. Inspired originally by the work of Habermas (as my Public Life and Late Capitalism emphasised), deliberative democrats are secretly Greek.

Convinced that democracy is quintessentially assembly democracy, or “participatory democracy”, they downplay the strategic and normative importance of courts, media platforms and other power-monitoring institutions and generally seem blind to the ubiquity and importance of elections and other forms of representation within political life.

So where do these analyses leave us? No doubt, critical consideration of the pathologies of populism, the weaknesses of “deliberative democracy” and the pitfalls of “left-wing populism” should force democrats of all persuasions to ask truly basic political questions, in support of viable democratic alternatives.

The historic task before us is not only to imagine new forms of democratic politics that aren’t infected with the spirit of populism. The goal must be to outflank populism politically by enabling democracy to dream of itself again, in other words, to strengthen monitory democracy by inventing adventurous new forms of democratic politics that don’t fall prey to big boss Leaders and their blarney and blather about “the people”.

At a minimum, this means not just more citizen involvement in public life but also inventing new forms of monitory democracy.

That calls for mechanisms with teeth capable of politically rolling back unaccountable corporate and state power, building non-carbon energy regimes and fostering greater social equality among participating citizens who value free and fair elections, welcome media diversity and feel utterly comfortable in the company of different others who are not treated as “enemies”, but as partners, strangers, colleagues and friends.

Democratic politics is a politics that democratises the sovereign people principle. It feels no urge to bow down and worship an imaginary fictional body called “The People”.

Democratic politics has regard for flesh-and-blood people in all their lived heterogeneity. It thus refuses the urge to smash up power-monitoring institutions, to label whole groups as out-groups and threaten them with violence and expulsion beyond “sovereign” borders that are deemed sacred.

What’s needed is much more monitory democracy, radically new ways of humbling and equitably redistributing power, wealth and life chances that expose populism for what it is: a form of counterfeit democracy.

Once upon a time, in the early years after 1945, such political redistribution went by the names of “progressivism”, “socialism”, “liberalism” and the “welfare state”.

In the harder times that are coming, what ecumenical name should we give to this new radical politics? Why don’t we simply call it “democracy”?

Authors: John Keane, Professor of Politics, University of Sydney

Read more http://theconversation.com/the-pathologies-of-populism-82593