New Zealand’s health service performs well, but inequities remain high

- Written by Jackie Cumming, Professor of Health Policy and Management, Victoria University of Wellington

This article is part of our global series about health systems, examining different health care systems all over the world.

New Zealand’s health care system is comprehensive and largely publicly funded. It generally performs well, but there are significant inequities in access and outcomes.

As international comparisons show, New Zealand’s health care is funded largely through taxation, and we spend less than other countries when measured by cost per person.

Health status in New Zealand

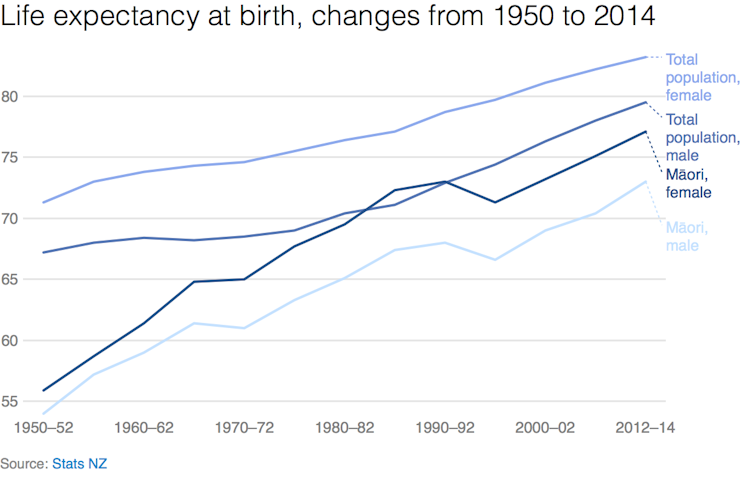

Overall, New Zealanders live relatively long and healthy lives. Life expectancy at birth sits at 81.4 years, above the OECD average of 80.5 years. It is below that of Australia, at 82.2 years, but higher than in the UK, at 81.1 years.

However, life expectancy is lower for Māori and Pacific populations by around six years. Māori and Pacific people are also two to three times more likely to die of conditions that could have been avoided if effective and timely health care had been available.

Another important metric is Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs), the sum of years of life lost from premature death and years lived with disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life, and New Zealanders have a loss in DALYs of around the average compared with other high-income countries.

In recent years, life expectancy has continued to improve for all population groups, and the number of DALYs lost has continued to fall, although, as noted above, health inequities remain stubbornly high.

How it works

Most of the funding for New Zealand’s health service comes from taxation, with government spending at NZ$16.2 billion in 2016/17 and NZ$16.78 billion in 2017/18. New Zealand generally spends less per capita on health care than other countries. In 2013, New Zealand spent $US3,328, less than the OECD average (US$3,453) and less than Australia (US$3,866), but more than the United Kingdom (US$3,235).

Compared to other countries, New Zealand tends to have a higher proportion of health expenditure from government sources.

The health system is overseen by a central minister and the Ministry of Health. Most health funding (75.6% of Vote Health) is channelled through 20 geographically distributed District Health Boards (DHBs), which are responsible for planning, delivering and funding services in their districts.

DHBs are governed by majority-elected boards and are accountable to the minister of health. They directly deliver hospital and hospital-led community services (such as district nursing services), and contract for primary health care services through 36 Primary Health Organisations (PHOs). These in turn contract with general practices or health care homes to delivery primary health care.

DHBs also hold contracts with a range of other primary health care providers, such as pharmacists and laboratories, and with many private for-profit and private not-for-profit organisations delivering community care (for example, services for mental health and home-based care for older people).

The Ministry of Health directly funds some national services, including disability support services for those aged under 65 years, public health services, well child services and midwifery services.

Performance measures

The New Zealand health service is generally seen to perform well. The structure of the service allows the government a good deal of control over total health spending and enables funding to follow key priorities.

International comparisons show that our health system demonstrates good value for money. It delivers higher than average life expectancy at birth. Although it has reduced the total number of DALYs lost slightly faster than the high-income country average, there are other countries that do better than New Zealand, perhaps due in part to New Zealand’s lower per capita cumulative spending in recent years.

Beyond such information, it is difficult to get a complete picture on the performance of New Zealand’s health service. There is no overarching framework or single repository of information on the service’s performance. We urgently need these to assess the system’s performance.

New Zealand data is often missing in the OECD’s health data sets. Therefore, the information provided below is selective.

Key health concerns

Mental health issues (including suicide), cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal conditions, dementia, injuries and oral health are New Zealand’s main health concerns. A number of them have common underlying risk factors, including smoking, poor diet, lack of physical activity, and abuse of alcohol and drugs, alongside occupational risks.

Smoking rates have come down over time, but remain stubbornly high for Māori. Poor diet and lack of physical activity remain key risk factors for the future.

In recent years, the New Zealand government has focused on a range of performance targets that it monitors. For the health-related “better public services” targets, New Zealand has seen increases in the rate of child immunisations, but not all DHBs and PHOs are hitting the target of 95% of eight-month-old babies being fully immunised.

Other trends show that most DHBs are meeting targets for increasing the number of elective operations and for ensuring that 95% of people are seen in an emergency department within six hours. Performance against the target for smokers to be offered assistance is also good, though a bit variable across DHBs and PHOs.

The targets for raising healthy kids (where 95% of obese children identified in the Before School Check programme should be offered a clinical assessment and family-based interventions) and for cancer treatment (to begin within 62 days for 85% of people) require more work in many DHBs.

However, New Zealand’s population is growing quickly. Although the government continually notes it is putting in significant amounts of new funding, once inflation and population growth are taken into account, there has been very little growth in the health budget since 2011.

The strain on services is appearing in media reports, highlighting poor performance in mental health (including high rates of suicide, especially amongst young people and Māori).

Increasing concerns are being expressed over problems people have in getting to maternity, oral health, cancer and elective services. This is likely to be leading New Zealanders to purchase private health insurance in increasing numbers, which raises concerns over ensuring there is equity of access within the health service, as those on higher incomes are more likely to buy insurance.

Comparison with other countries

In a recent analysis, the Commonwealth Fund compared the performance of New Zealand’s health service with 10 other countries. It ranks New Zealand fourth out of 11 countries. It shows that we do well with respect to administrative efficiency (reducing time spent on claims, delays from coverage restrictions, visits to emergency departments when people could have been treated by their regular doctor) and care processes (those with health issues talking with a doctor, doctors having access to electronic clinical decision support, co-ordinated care measures, and engagement and patient preferences).

However, there is clear room for improvement on some of these measures. For example, only 37% of people discuss their weight with their doctor, even though obesity is a major issue in New Zealand.

On other issues, New Zealand performs less well. The cost of medical care is a key concern. Commonwealth Fund and New Zealand data show alarmingly high rates of unmet need due to cost, particularly for Māori and Pacific women and women in the areas of lower socio-economic status.

There are also high rates of unfilled prescriptions for Māori, Pacific and lower-income people, compared with the total population. The Commonwealth Fund data also show poor access to dental care in New Zealand compared with other countries.

Equity remains an issue in New Zealand, according to the Commonwealth Fund analysis. A growing gap between high and low income earners means that more people feel they can’t afford medical and dental care.

Also of concern are comparatively high rates of infant mortality, deaths following stroke and the number of medication or lab test errors. However, New Zealand does well in relation to breast and colon cancer survival rates.

Where to from here

New Zealand’s health care system is a form of the Beveridge model, in which health care is financed by the government through tax payments, just like the police force or the public library.

It was introduced during a Labour government, led by Michael Joseph Savage, which is best remembered for its landmark “cradle to grave” social welfare reforms, especially the Social Security Act 1938.

That act overhauled and extended social security benefits to “safeguard” New Zealanders’ income. Among other measures, it provided income support, benefits for widows, orphans, invalids and families and universal support for older people through aged benefits and superannuation. It also introduced universal and free hospital, maternity and other health care services, as well as benefits to support access to general practitioner (GP) services.

The health service today supports a similar range of services, with the addition of a no-fault accident compensation scheme, known as ACC.

But New Zealand’s population is growing rapidly and ageing. Projections are that significantly more people will develop chronic conditions in future years.

Since 2001, a key focus has been on strengthening primary health care to deliver services closer to home, in community settings and with a stronger emphasis on prevention. There is, however, little evidence that primary health care is receiving a higher proportion of funding than in earlier years and doubts remain over whether we are reducing demands on hospitals as a result.

Of particular concern are the fees people must pay to see their GP and the levels of unmet need being reported as a result. New Zealand must address this issue if it is truly to encourage the development and use of primary health care services.

There are increasing signs of strain and inequities remain a real problem, both in terms of health status and access to care.

Like all countries, New Zealand must continue to work hard to support its health service and search for ways to continually ensure it provides effective services and good value for money, while working to reduce inequities. Without this, achieving the original goals of the Social Security Act of 1938 will become a distant memory.

Another important metric is Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs), the sum of years of life lost from premature death and years lived with disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life, and New Zealanders have a loss in DALYs of around the average compared with other high-income countries.

In recent years, life expectancy has continued to improve for all population groups, and the number of DALYs lost has continued to fall, although, as noted above, health inequities remain stubbornly high.

How it works

Most of the funding for New Zealand’s health service comes from taxation, with government spending at NZ$16.2 billion in 2016/17 and NZ$16.78 billion in 2017/18. New Zealand generally spends less per capita on health care than other countries. In 2013, New Zealand spent $US3,328, less than the OECD average (US$3,453) and less than Australia (US$3,866), but more than the United Kingdom (US$3,235).

Compared to other countries, New Zealand tends to have a higher proportion of health expenditure from government sources.

The health system is overseen by a central minister and the Ministry of Health. Most health funding (75.6% of Vote Health) is channelled through 20 geographically distributed District Health Boards (DHBs), which are responsible for planning, delivering and funding services in their districts.

DHBs are governed by majority-elected boards and are accountable to the minister of health. They directly deliver hospital and hospital-led community services (such as district nursing services), and contract for primary health care services through 36 Primary Health Organisations (PHOs). These in turn contract with general practices or health care homes to delivery primary health care.

DHBs also hold contracts with a range of other primary health care providers, such as pharmacists and laboratories, and with many private for-profit and private not-for-profit organisations delivering community care (for example, services for mental health and home-based care for older people).

The Ministry of Health directly funds some national services, including disability support services for those aged under 65 years, public health services, well child services and midwifery services.

Performance measures

The New Zealand health service is generally seen to perform well. The structure of the service allows the government a good deal of control over total health spending and enables funding to follow key priorities.

International comparisons show that our health system demonstrates good value for money. It delivers higher than average life expectancy at birth. Although it has reduced the total number of DALYs lost slightly faster than the high-income country average, there are other countries that do better than New Zealand, perhaps due in part to New Zealand’s lower per capita cumulative spending in recent years.

Beyond such information, it is difficult to get a complete picture on the performance of New Zealand’s health service. There is no overarching framework or single repository of information on the service’s performance. We urgently need these to assess the system’s performance.

New Zealand data is often missing in the OECD’s health data sets. Therefore, the information provided below is selective.

Key health concerns

Mental health issues (including suicide), cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal conditions, dementia, injuries and oral health are New Zealand’s main health concerns. A number of them have common underlying risk factors, including smoking, poor diet, lack of physical activity, and abuse of alcohol and drugs, alongside occupational risks.

Smoking rates have come down over time, but remain stubbornly high for Māori. Poor diet and lack of physical activity remain key risk factors for the future.

In recent years, the New Zealand government has focused on a range of performance targets that it monitors. For the health-related “better public services” targets, New Zealand has seen increases in the rate of child immunisations, but not all DHBs and PHOs are hitting the target of 95% of eight-month-old babies being fully immunised.

Other trends show that most DHBs are meeting targets for increasing the number of elective operations and for ensuring that 95% of people are seen in an emergency department within six hours. Performance against the target for smokers to be offered assistance is also good, though a bit variable across DHBs and PHOs.

The targets for raising healthy kids (where 95% of obese children identified in the Before School Check programme should be offered a clinical assessment and family-based interventions) and for cancer treatment (to begin within 62 days for 85% of people) require more work in many DHBs.

However, New Zealand’s population is growing quickly. Although the government continually notes it is putting in significant amounts of new funding, once inflation and population growth are taken into account, there has been very little growth in the health budget since 2011.

The strain on services is appearing in media reports, highlighting poor performance in mental health (including high rates of suicide, especially amongst young people and Māori).

Increasing concerns are being expressed over problems people have in getting to maternity, oral health, cancer and elective services. This is likely to be leading New Zealanders to purchase private health insurance in increasing numbers, which raises concerns over ensuring there is equity of access within the health service, as those on higher incomes are more likely to buy insurance.

Comparison with other countries

In a recent analysis, the Commonwealth Fund compared the performance of New Zealand’s health service with 10 other countries. It ranks New Zealand fourth out of 11 countries. It shows that we do well with respect to administrative efficiency (reducing time spent on claims, delays from coverage restrictions, visits to emergency departments when people could have been treated by their regular doctor) and care processes (those with health issues talking with a doctor, doctors having access to electronic clinical decision support, co-ordinated care measures, and engagement and patient preferences).

However, there is clear room for improvement on some of these measures. For example, only 37% of people discuss their weight with their doctor, even though obesity is a major issue in New Zealand.

On other issues, New Zealand performs less well. The cost of medical care is a key concern. Commonwealth Fund and New Zealand data show alarmingly high rates of unmet need due to cost, particularly for Māori and Pacific women and women in the areas of lower socio-economic status.

There are also high rates of unfilled prescriptions for Māori, Pacific and lower-income people, compared with the total population. The Commonwealth Fund data also show poor access to dental care in New Zealand compared with other countries.

Equity remains an issue in New Zealand, according to the Commonwealth Fund analysis. A growing gap between high and low income earners means that more people feel they can’t afford medical and dental care.

Also of concern are comparatively high rates of infant mortality, deaths following stroke and the number of medication or lab test errors. However, New Zealand does well in relation to breast and colon cancer survival rates.

Where to from here

New Zealand’s health care system is a form of the Beveridge model, in which health care is financed by the government through tax payments, just like the police force or the public library.

It was introduced during a Labour government, led by Michael Joseph Savage, which is best remembered for its landmark “cradle to grave” social welfare reforms, especially the Social Security Act 1938.

That act overhauled and extended social security benefits to “safeguard” New Zealanders’ income. Among other measures, it provided income support, benefits for widows, orphans, invalids and families and universal support for older people through aged benefits and superannuation. It also introduced universal and free hospital, maternity and other health care services, as well as benefits to support access to general practitioner (GP) services.

The health service today supports a similar range of services, with the addition of a no-fault accident compensation scheme, known as ACC.

But New Zealand’s population is growing rapidly and ageing. Projections are that significantly more people will develop chronic conditions in future years.

Since 2001, a key focus has been on strengthening primary health care to deliver services closer to home, in community settings and with a stronger emphasis on prevention. There is, however, little evidence that primary health care is receiving a higher proportion of funding than in earlier years and doubts remain over whether we are reducing demands on hospitals as a result.

Of particular concern are the fees people must pay to see their GP and the levels of unmet need being reported as a result. New Zealand must address this issue if it is truly to encourage the development and use of primary health care services.

There are increasing signs of strain and inequities remain a real problem, both in terms of health status and access to care.

Like all countries, New Zealand must continue to work hard to support its health service and search for ways to continually ensure it provides effective services and good value for money, while working to reduce inequities. Without this, achieving the original goals of the Social Security Act of 1938 will become a distant memory.

Authors: Jackie Cumming, Professor of Health Policy and Management, Victoria University of Wellington