Vietnam's typhoon disaster highlights the plight of its poorest people

- Written by Chinh Luu, PhD candidate in Disaster Management, University of Newcastle

Six people lost their lives when Typhoon Doksuri smashed into central Vietnam on September 16, the most powerful storm in a decade to hit the country.

Although widespread evacuations prevented a higher death toll, the impact on the region’s most vulnerable people will be extensive and lasting.

Read more: Typhoon Haiyan: a perfect storm of corruption and neglect.

Government sources report that more than 193,000 properties have been damaged, including 11,000 that were flooded. The storm also caused widespread damage to farmland, roads, and water and electricity infrastructure. Quang Binh and Ha Tinh provinces bore the brunt of the damage.

Typhoon Doksuri’s aftermath.

EPA

Typhoon Doksuri’s aftermath.

EPA

Central Vietnam is often in the path of tropical storms and depressions that form in the East Sea, which can intensify to form tropical cyclones known as typhoons (the Pacific equivalent of an Atlantic hurricane).

Typhoon Doksuri developed and tracked exactly as forecast, meaning that evacuations were relatively effective in saving lives. What’s more, the storm moved quickly over the affected area, delivering only 200-300 mm of rainfall and sparing the region the severe flooding now being experienced in Thailand.

Doksuri is just one of a spate of severe tropical cyclones that have formed in recent weeks, in both the Pacific and Atlantic regions. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and, most recently, Maria have attracted global media coverage, much of it focused on rarely considered angles such as urban planning, poverty, poor development, politics, the media coverage of disasters – as well as the perennial question of climate change.

Disasters are finally being talked about as part of a discourse of systemic oppression - and this is a great step forward.

Vietnam’s vulnerability

In Vietnam, the root causes of disasters exist below the surface. The focus remains on the natural hazards that trigger disasters, rather than on the vulnerable conditions in which many people are forced to live.

Unfortunately, the limited national disaster data in Vietnam does not allow an extensive analysis of risk. Our research in central Vietnam is working towards filling this gap and the development of more comprehensive flood mitigation measures.

Central Vietnam has a long and exposed coastline. It consists of 14 coastal provinces and five provinces in the Central Highlands. The Truong Son mountain range rises to the west and the plains that stretch to the coast are fragmented and narrow. River systems are dense, short and steep, with rapid flows.

These physical characteristics often combine with widespread human vulnerability, to deadly effect. We can see this in the impact of Typhoon Doksuri, but also to a lesser extent in the region’s annual floods.

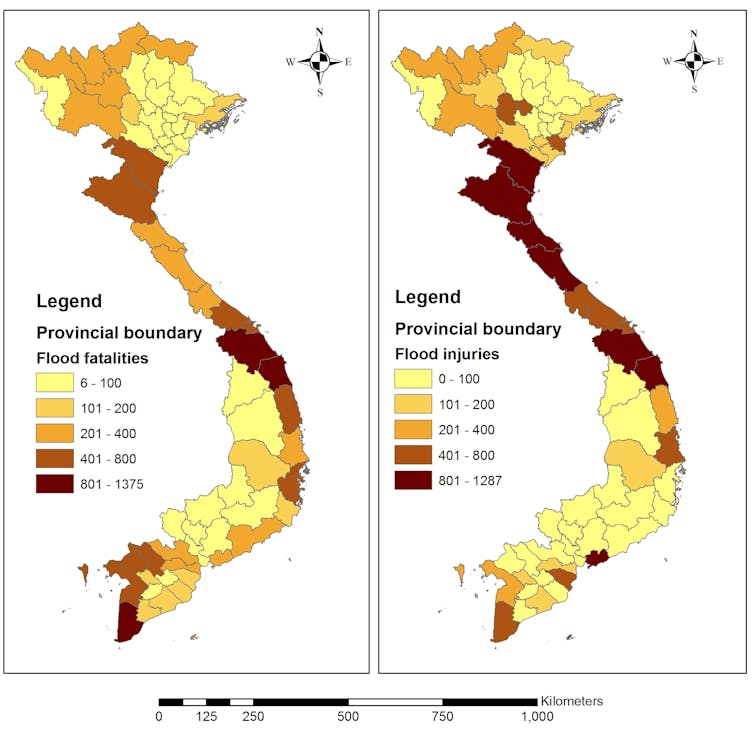

Flood risk map by province using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making method and the national disaster database.

Author provided

Flood risk map by province using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making method and the national disaster database.

Author provided

Rapid population growth, industrial development and agricultural expansion have all increased flood risk, especially in Vietnam’s riverine and coastal areas. Socially marginalised people often have to live in the most flood-prone places, sometimes as a result of forced displacement.

Floods and storms therefore have a disproportionately large effect on poorer communities. Most people in central Vietnam depend on their natural environment for their livelihood, and a disaster like Doksuri can bring lasting suffering to a region where 30-50% of people are already in poverty.

When disaster does strike, marginalised groups face even more difficulty because they typically lack access to public resources such as emergency relief and insurance.

The rural poor will be particularly vulnerable after this storm. Affected households have received limited financial support from the local government, and many will depend entirely on charity for their recovery.

Better research, less bureaucracy

This is not to say that Vietnam’s government did not mount a significant effect to prepare and respond to Typhoon Doksuri. But typically for Vietnam, where only the highest levels of government are trusted with important decisions, the response was bureaucratic and centralised.

This approach can overlook the input of qualified experts, and lead to decisions being taken without enough data about disaster risk.

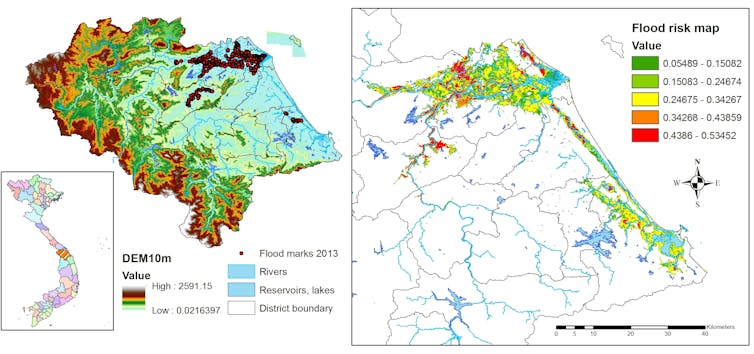

Our research has generated a more detailed picture of disaster risk (focused on flood hazard) in the region. We have looked beyond historical loss statistics and collected data on hazards, exposure and vulnerability in Quang Nam province.

Left: flooding hazard map for Quang Nam province. Right: risk of flooding impacts on residents, calculated on the basis of flood hazards from the left map, plus people’s exposure and vulnerability.

Author provided

Left: flooding hazard map for Quang Nam province. Right: risk of flooding impacts on residents, calculated on the basis of flood hazards from the left map, plus people’s exposure and vulnerability.

Author provided

Our findings show that much more accurate, sensitive and targeted flood protection is possible. The challenge is to provide it on a much wider scale, particularly in poor regions of the world.

Reduce risk, and avoid creating new risk

An effective risk management approach can help to reduce the impacts of flooding in central Vietnam. Before a disaster ever materialises, we can work to reduce risk - and avoid activities that exacerbate it - for example land grabbing for development, displacing the poor, environmental degradation, discrimination against minorities.

Read more: Irma and Harvey: very different storms, but both affected by climate change.

It is critical that subject experts, particularly scientists, are involved in decisions about disaster risk - in Vietnam and around the world. There must be a shift to more proactive approaches, guided by deep knowledge both of the local context and of the latest scientific advances.

Our maps will help planners and politicians to recognise high-risk areas, prepare flood risk plans, and set priorities for both flood defences and responses to vulnerability. The maps are also valuable tools for communication.

But at the same time as emphasising data-driven decisions, we also need to advocate for a humanising approach in dealing with some of the most oppressed, marginalised, poor and disadvantaged members of the global community.

Authors: Chinh Luu, PhD candidate in Disaster Management, University of Newcastle