After 30 years of the Montreal Protocol, the ozone layer is gradually healing

- Written by Andrew Klekociuk, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, University of Tasmania

This weekend marks the 30th birthday of the Montreal Protocol, often dubbed the world’s most successful environmental agreement. The treaty, signed on September 16, 1987, is slowly but surely reversing the damage caused to the ozone layer by industrial gases such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Each year, during the southern spring, a hole appears in the ozone layer above Antarctica. This is due to the extremely cold temperatures in the winter stratosphere (above 10km altitude) that allow byproducts of CFCs and related gases to be converted into forms that destroy ozone when the sunlight returns in spring.

As ozone-destroying gases are phased out, the annual ozone hole is generally getting smaller – a rare success story for international environmentalism.

Back in 2012, our Saving the Ozone series marked the Montreal Protocol’s silver jubilee and reflected on its success. But how has the ozone hole fared in the five years since?

Read more: What is the Antarctic ozone hole and how is it made?.

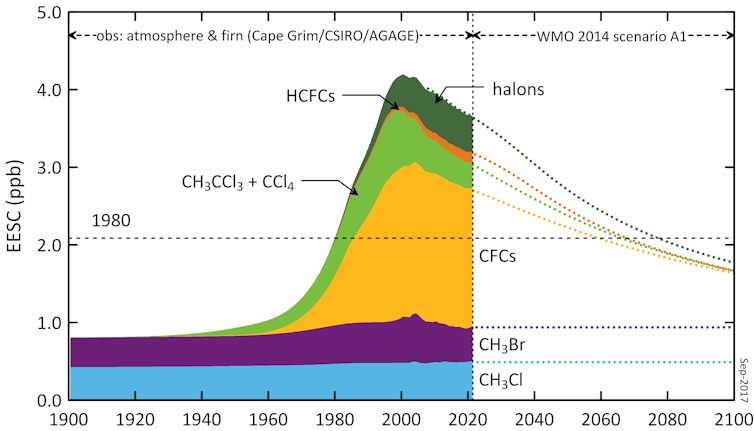

The Antarctic ozone hole has continued to appear each spring, as it has since the late 1970s. This is expected, as levels of the ozone-destroying halocarbon gases controlled by the Montreal Protocol are still relatively high. The figure below shows that concentrations of these human-made substances over Antarctica have fallen by 14% since their peak in about 2000.

Past and predicted levels of controlled gases in the Antarctic atmosphere, quoted as equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine (EESC) levels, a measure of their contribution to stratospheric ozone depletion.

Paul Krummel/CSIRO, Author provided

Past and predicted levels of controlled gases in the Antarctic atmosphere, quoted as equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine (EESC) levels, a measure of their contribution to stratospheric ozone depletion.

Paul Krummel/CSIRO, Author provided

It typically takes a few decades for these gases to cycle between the lower atmosphere and the stratosphere, and then ultimately to disappear. The most recent official assessment, released in 2014, predicted that it will take 30-40 years for the Antarctic ozone hole to shrink to the size it was in 1980.

Signs of recovery

Monitoring the ozone hole’s gradual recovery is made more complicated by variations in atmospheric temperatures and winds, and the amount of microscopic particles called aerosols in the stratosphere. In any given year these can make the ozone hole bigger or smaller than we might expect purely on the basis of halocarbon concentrations.

Launching an ozone-measuring balloon from Australia’s Davis Research Station in Antarctica.

Barry Becker/BOM/AAD, Author provided

Launching an ozone-measuring balloon from Australia’s Davis Research Station in Antarctica.

Barry Becker/BOM/AAD, Author provided

The 2014 assessment indicated that the size of the ozone hole varied more during the 2000s than during the 1990s. While this might suggest it has become harder to detect the healing effects of the Montreal Protocol, we can nevertheless tease out recent ozone trends with the help of sophisticated atmospheric chemistry models.

Reassuringly, a recent study showed that the size of the ozone hole each September has shrunk overall since the turn of the century, and that more than half of this shrinking trend is consistent with reductions in ozone-depleting substances. However, another study warns that careful analysis is needed to account for a variety of natural factors that could confound our detection of ozone recovery.

The 2015 volcano

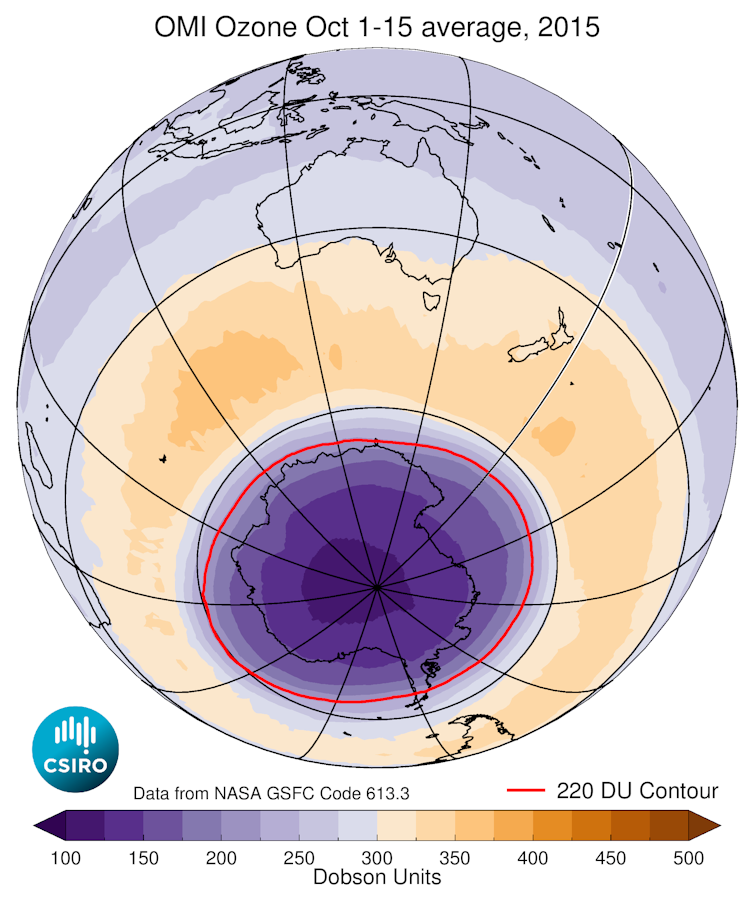

One such factor is the presence of ozone-destroying volcanic dust in the stratosphere. Chile’s Calbuco volcano seems to have played a role in enhancing the size of the ozone hole in 2015.

At its maximum size, the 2015 hole was the fourth-largest ever observed. It was in the top 15% in terms of the total amount of ozone destroyed. Only 2006, 1998, 2001 and 1999 had more ozone destruction, whereas other recent years (2013, 2014 and 2016) ranked near the middle of the observed range.

Average ozone concentrations over the southern hemisphere during October 1-15, 2015, when the Antarctic ozone hole for that year was near its maximum extent. The red line shows the boundary of the ozone hole.

Paul Krummel/CSIRO/EOS, Author provided

Average ozone concentrations over the southern hemisphere during October 1-15, 2015, when the Antarctic ozone hole for that year was near its maximum extent. The red line shows the boundary of the ozone hole.

Paul Krummel/CSIRO/EOS, Author provided

Another notable feature of the 2015 ozone hole was that it was at its biggest observed extent for much of the period from mid-October to mid-December. This coincided with a period during which the jet of westerly winds in the Antarctic stratosphere was particularly unaffected by the warmer, more ozone-rich air at lower latitudes. In a typical year, the influx of air from lower latitudes helps to limit the size of the ozone hole in spring and early summer.

The 2017 hole

As noted above, the ozone holes of 2013, 2014 and 2016 were relatively unremarkable compared with that of 2015, being close to the long-term average for overall ozone loss.

In general respects, these ozone holes were similar to those seen in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before the peak of ozone depletion. This is consistent with a gradual recovery of the ozone layer as levels of ozone-depleting substances gradually decline.

This year’s hole began to form in early August, and the timing was similar to the long-term average. Stratospheric temperatures during the Antarctic winter were slightly cooler than in 2016, which would favour enhancement of the chemical changes that lead to ozone destruction in spring. However, temperatures climbed above average in mid-August during a disturbance to the polar winds, delaying the hole’s expansion. As of the second week of September, the warmer-than-average temperatures have continued but the ozone hole has grown slightly larger than the long-term average since 1979.

Read more: Saving the ozone layer: why the Montreal Protocol worked.

While annual monitoring continues, which includes measurements under the Australian Antarctic Program, a more comprehensive assessment of the ozone layer’s prospects is set to arrive late next year. Scientists across the globe, coordinated by the UN Environment Program and the World Meteorological Organisation, are busy preparing the next report required under the Montreal Protocol, called the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2018.

This peer-reviewed report will examine the recent state of the ozone layer and the atmospheric concentration of ozone-depleting chemicals, how the ozone layer is projected to change, and links between ozone change and climate.

In the meantime we’ll watch the 2017 hole as it peaks then shrinks over the remainder of the year, as well as the ozone holes of future years, which will tend to grow less and less large as the ozone layer heals.

Authors: Andrew Klekociuk, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, University of Tasmania