Mythical, slippery, shapeshifting: Grief is the Thing With Feathers transforms tragedy into literature

- Written by Jen Webb, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Creative Practice, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra

Max Porter lost his father when he was just six years old. He has described his first book, Grief is the Thing with Feathers, as “a love letter to my dad”.

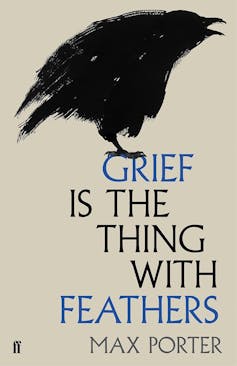

A huge bestseller when it was published in 2015, it is one of many books in literary history that deal with grief – whether it is the author’s own experience, or a grief observed. It tells the story of the husband and sons of a woman who has died suddenly. The three are not coping with the shock and absence of this bereavement. Into this situation comes a most unlikely character: Crow.

We have been alerted to this possibility. The title of the book is adapted from Emily Dickinson’s poem “Hope” is the thing with feathers; and the epigraph is also taken from her poetry: “That Love is all there is…”.

Borrowing Dickinson’s habit of editing her poems by hand, Porter crosses out “love” and replaces it with “crow”.

Is he real? On the one hand, of course not. He is the shape of grief, a metaphor Dad clings to as he writes his book, as he cares for his boys, as he mourns his wife. He guides Dad through memories and into anticipation of future events; and as we watch, Dad begins to re-emerge under Crow’s direction.

On the other hand, of course Crow is real. He scatters feathers; he leaves “little squitty shits in places I knew he’d never clean”. The boys listen to him practise his speeches in the bathroom “where he often is because he likes the acoustics”. They hear him fighting with Dad, all “cronks, barks, sobs, a weird gamelan jam of broken father sounds and violent bird calls”.

Crow remains real to them, even as adults, men with their own families:

I tell tales of our family friend, the crow. My wife shakes her head. She thinks it’s weird that I fondly remember family holidays with an imaginary crow, and I remind her that it could have been anything, could have gone any way, but something more or less healthy happened. We miss our Mum, we love our Dad, we wave at crows.

To be real and imagined; to be grieving and able to function; to be poem and prose: this little book deals with such in-between states. By the end, when Crow leaves, his work done, and the Boys and Dad scatter Mum’s ashes, we are left not with knowledge about grief, or about Ted Hughes, or about giant crows, but with a gentle resonance.

It’s not surprising this book launched a significant writing career. Grief is the Thing with Feathers, published in 2015 and winner of the 2016 International Dylan Thomas Prize, was followed in 2019 by Lanny, another book animated by the fantastical – and by grief, loss and hope.

Porter’s third book The Death of Francis Bacon (2021), a book of fragments of that artist’s last days, again presses up against the edges of what writing can do. His most recent work Shy (2023) is a portrait of an adolescent youth who fails and is failed by society.

Porter’s stories are of people on the margins, people struggling against adversities. He tells those tales in fragments, flickering images, surprising swirls of language and wit.

But Grief is the Thing with Feathers remains the book that has captured the public imagination. It has been adapted for stage – by Enda Walsh, starring Cillian Murphy at the Barbican in London, and again, directed by Simon Phillips, due to open at Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney this weekend. Its next public outing is as the movie The Thing with Feathers, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, scheduled for release in November.

Whether a book, play or movie, Grief is the Thing with Feathers is well worth the price of admission.

Authors: Jen Webb, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Creative Practice, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra