Australian poetry used to be popular. And it could be again

- Written by Paul Hetherington, Emeritus Professor of Writing, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra

Dorothea Mackellar’s poem from 1908, My Country, is famous in Australia despite its outmoded colonial assumptions. Many people are able to quote its lines about ragged mountain ranges, droughts and flooding rains.

However, in this election year, it is worth asking why most contemporary Australian poetry is not more widely read and whether the federal government might try to address this issue. This question has increased relevance in the context of the government’s commitment to appoint an Australian poet laureate in 2025.

In many countries, poetry is recognised within the heart of cultural life. It represents a way of expressing key ideas, feelings and values, and of telling stories central to a society’s collective senses of identity.

So why isn’t poetry more popular in Australia, why should you care and what could help it flourish? Is this a matter of education?

Our poetic history

Poetry was integral to Australian culture for the decades before and after Federation.

The first edition of Banjo Paterson’s poetry collection, The Man from Snowy River, and Other Verses (1890) sold 7,000 copies in its first few months

In 1915, C.J. Dennis published The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke, which had three editions in 1915, nine in 1916, and three in 1917.

Written in a colloquial voice, this poetry remains highly evocative:

The wet sands glistened, an’ the gleamin’ moon

Shone yeller on the sea, all streakin’ down

Dennis’ sequel, The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916) had a first run of 39,324 copies even though Australia’s population was less than five million people. In comparison, one of Australia’s best-selling recent poetry titles, Evelyn Araluen’s Drop Bear, sold over 25,000 copies. This is a wonderful achievement, although it is worth noting the Australian population has grown more than five times in size since 1916.

More generally, over recent decades, the complexity and diversity of Australian society has greatly increased but the overall sales for Australian literary titles, including poetry, has been in decline. Candice J. Fox (author and academic at University of Notre Dame Sydney) attributes this to a changing readership, shrinking government arts funding and changing market practices.

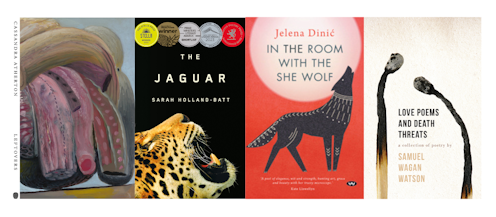

At the time of writing, University of Queensland Press confirmed that the most awarded recent Australian poetry title, Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar, has sold over 10,000 copies.

Currently only one in ten Australians read any poetry.

Australian poetry today

In 2025, most Australian poetry books, usually published by small presses with limited distribution, sell in the hundreds rather than the thousands. Some sell even fewer copies. Many are never reviewed.

There are various reasons for this. One is that not enough poetry is taught in schools, and many teachers at all levels of education lack confidence in teaching poetry.

Poetry is characterised by the complex use of language and approaching it can be daunting for anyone. Yet if an Australian Poet Laureateship involved funding an expansive national schools program that made poetry a central feature of the curriculum, and included teacher training, many more teachers and students would feel confident in reading poetry in the future.

For a fairly modest investment, books by Australian poets could be bought by the government in large quantities and distributed to all schools in the country. With guaranteed sales from such a program, mainstream publishers may regain an interest in poetry.

Why it’s important

Some people might think the problem with contemporary Australian poetry is that much of it is too obscure or too narrowly focused to be of general interest. But a good deal of Australian poetry is accessible. For example, David Malouf begins a poem with a familiar vision of urban life:

A city of too much glass; too many walls

Furthermore, Australian poetry is remarkably diverse, and a wide selection of contemporary titles would speak directly to Australia’s most important issues. These include a better understanding of Indigenous culture, history, gender and cultural diversity and ways of understanding life’s different stages and associated interpersonal matters.

Poetry is also partly about play and the enjoyment of self-expression. The curriculum I imagine might include opportunities for all secondary school students to write their own poetry.

Widely disseminating Australian poetry through a national schools program could be a way for people to encounter more intricate forms of speaking and ways of thinking than they are likely to find on social media or in the mass media.

Reading poetry provides a useful education in the deployment of subtle and striking language. It provides an opportunity to develop readers’ capacity for nuanced judgements.

A new path

There has been an upsurge in Australian prose poetry recently, led by poets such as Cassandra Atherton, who has a vital interest in intimacy and feminist issues. She writes:

at sunset, your heart burns a hole in my ruby slippers.

Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar addresses her father’s ageing in memorable ways:

for the first time, the last time

he wants to live.

Jelena Dinic writes in Serbian and English and In the Room with the She Wolf includes poetry that traverses cultures, as she states:

I cry in mother tongue

Samuel Wagan Watson, one of many fine contemporary Indigenous poets, challenges the reader with lines such as:

Wash my eyes from censored images of history.

Australians should not only know about these poets, and numerous others, but they should be taught to understand the many insights they contribute to our cultural and social life. Poetry could certainly be popular again but, firstly, we all need to remember how much it matters.

Authors: Paul Hetherington, Emeritus Professor of Writing, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra

Read more https://theconversation.com/australian-poetry-used-to-be-popular-and-it-could-be-again-250399