Michelle de Kretser writes back to the ‘Woolfmother’ in Theory Practice

- Written by Eda Gunaydin, Lecturer, International Studies, University of Wollongong

The narrator of Michelle de Kretser’s seventh novel Theory & Practice is younger than I was when she realises something we all do, eventually: sometimes there can be a great chasm between what we say, write, and purport to know and believe, and what we do.

She is 24, studying at a Melbourne university, and struggling to finish her thesis on Virginia Woolf. She is full of feminist conviction, but finds it difficult to sustain in the face of the limitations of the institution, her subject, and herself.

Her teachers and supervisors prescribe a healthy dose of French poststructuralist theory, which is putatively progressive, but tells her little about how to live. Her feminist colleagues, like Woolf herself, have blind spots around race that are the size of continents. And the narrator tries and fails to resist her desire for a mining engineering student named Kit, which pits her, against her will, against fellow arts student Olivia.

Review: Theory & Practice – Michelle de Kretser (Text Publishing)

All of these narrative threads are deeply recognisable. I remember the frustration I felt in my early 20s, studying literary theory. One of the most meaningless and passionless essays I ever submitted as an undergraduate was on Hélène Cixous’s Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing (1990), heralded as a masterpiece of feminist literary theory. I realised, weeks after submitting it, that I had mixed up the words “avow” and “disavow” throughout. This had made my entire argument collapse in on itself. Nevertheless, the essay was awarded a High Distinction.

I later disavowed postructuralism in favour of materialist politics, which made my work less trendy, but me feel more fulfilled. And I can also remember the deep sadness I felt when feminist and postcolonial colleagues failed to embody the principles they professed to hold.

Theory & Practice works effectively on two levels. It tackles the notion of “women’s fiction”, theoretically and practically. It is knowing and assured in its treatment of gender, threading references to Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own with French theorists like Cixous, who coined the term écriture feminine (women’s writing), which attempts to build an account of a feminine style of ordering and using language.

At times, the protagonist questions these teachings, though we learn that she believes, on some level, in the universality of gendered oppression. De Kretser writes powerfully about the ubiquity of sexual assault under patriarchy, which draws her back to Woolf, despite the racism she finds in Woolf’s diaries.

The narrator’s relationship with other women is depicted with just as much nuance. De Kretser captures the betrayals, jealousies and failures of sisterhood, deftly balancing realistic depictions of romantic competition and scorn with depictions of friendship and enduring love.

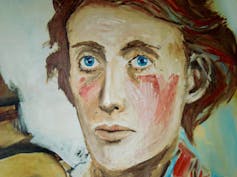

The protagonist’s relationship with her mother and her symbolic mothers – her female mentors as she comes of age as an artist – are particularly striking. She dubs Virginia Woolf her “Woolfmother”: the person she believes shows her “how to understand ourselves in relation to the world”. She tacks a picture of Woolf above her desk, later moving it to the door.

Her biological mother – widowed and fretting – also intrudes frequently into the narrative. The narrator returns occasionally to thoughts of her family’s migration to Australia and her mother’s modest life, as she mingles with the bohemians of St Kilda and experiences the class mobility afforded her.

As she matures, the influence of both mothers recedes – or inverts, as the narrator starts to feel like the mother of her mother.

Theory & Practice is a novel that takes women’s art and interiority seriously, something de Kretser is able to accomplish because she herself is a serious artist.

It also works on two levels in its experimentation with form. Blending fiction, essay and memoir, the novel uses a hybrid form to comment on form itself. It draws inspiration from Woolf’s novel The Years (1937), which Woolf intended to be a “novel-essay”, though by the time it was finished, as Theory & Practice’s narrator notes, the “sole trace” that remained of this original intention was the book’s “marked interest in public life”.

Despite her intentions, and her many accomplishments as a non-fiction writer (including essays, diaries and criticism), Woolf’s attempts to write novel-essays or to imbue her fiction with non-fiction elements often resulted in fiction. Throughout her life, she was ambivalent about hybrid forms. Although she was a prolific essayist, Woolf occasionally railed against the form’s evolution during her lifetime. In The Decay of Essay Writing (1905), she decried the personal essay, attributing its rise to a desire to give “fresh and amusing shape […] to the old commodities – for we really have nothing so new to say that it will not fit into one of the familiar forms”.

And yet, in theory, it is this hybrid quality that allows resistant literature to be written. Marxist literary theorists like Georg Lukács and Theodor Adorno emphasise the potential of essays to synthesise knowledge and art. Scholars of Woolf’s essays have argued that their hybridity enabled Woolf to achieve her feminist aims, as it allowed for “exploration of the intersections between private and public, personal and political”.

Theory & Practice takes up this exploration of the intersections between private and public, personal and political. The narrator is disillusioned by the gap between Woolf’s “theorising of women’s lives in ground-breaking books” and the insupportable racism in the diaries.