Fredric Jameson, the world’s greatest Marxist critic, is dead – long live Utopia!

- Written by Julian Murphet, Jury Professor of English and Language and Literature, University of Adelaide

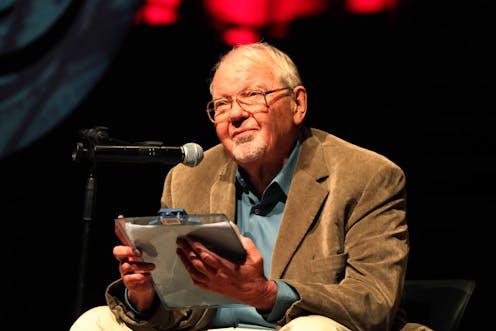

There are writers and critics, theorists and gurus. And then there is Fredric Jameson. Or there was. Because on September 22, at the age of 90, undimmed and over-productive as ever (three books in 2024 alone!), Jameson passed quietly away.

Over the course of his long and influential career, Jameson published 34 books and hundreds of articles. Along with his legendary conference interventions, they attest to perhaps the single most generous and sustained act of attention to cultural forms in human history.

His work took in a mind-boggling array of materials. Colin MacCabe once quipped that “nothing cultural was alien to him”. Though Jameson’s training was in German and French literature (under Wayne C. Booth and Erich Auerbach), he went on to master Western Marxism and French theory, before turning his tireless mind to architecture, theatre, film, television, opera, symphonic form, pulp fiction, painting, and what seemed to be every book written in any language worthy of our attention.

The title of world’s greatest Marxist critic has stuck to Jameson for over 50 years. There is no heir apparent. There is instead a vast international network of protégées, disciples, acolytes and apostles, who will endeavour to keep hope alive in the gathering darkness.

Hope is a word not often used in Jameson’s monumental oeuvre. He rightly preferred a more literary term: utopia. It defined him. Irradiated by what it portended – an achievable world freed from drudgery and stupidity and structural inequality – his prose sifted the cultural and artistic sediment of three centuries of capitalist domination.

Jameson held aloft for our astonished recognition the gleaming nuggets where traces of the good life lay coiled.

Generosity and the dialectic

Generosity is not a byword in the critical circles of the left. Where others invariably scrapped and stooped to bitter sectarian disputes, Jameson took the higher ground. He called it “the dialectic”, a habit of thought in which oppositions could be held comfortably in mind while the pulse of history rang out.

He was attacked for it, often nastily, and there must have been animosities and personal vendettas accrued over the years, but they never manifested in his published work. In the conclusion to his most famous book, Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1989), Jameson took on dozens of snide critiques. It is a masterclass in outflanking the enemy by seeing their point of view and then turning it around on itself.